Jerry Bowyer

Buzzcharts: we're all inflation hawks now

By Jerry Bowyer

Back in 2006, when the federal-funds rate peaked at 5.25 percent, several economists writing for National Review Online argued that the Federal Reserve was too tight. We also held that the gold price, which was climbing higher at the time, was not an unerring Polaris around which all other inflation indicators (such as exchange rates, nominal interest rates, and yield curves) must revolve. We wrote that the system was running the risk of too little liquidity, not too much.

One the other side of the debate, several economists writing for NRO argued that the Fed was too loose, and that it likely would be forced to raise rates. They generally predicted runaway inflation if the Fed cut rates at all within a relatively short period of time (up to two years). They predicted that long-term interest rates and mortgage rates would accordingly rise to very high levels. They believed this, largely, because of increases in the price of gold.

Buzzcharts will let open-minded observers mull over which, if any, side has been vindicated by ensuing events. We come not to shake things up, but to shake hands; not to pick a fight with our friends on the supply-side, but instead to pick a fight with our central bank.

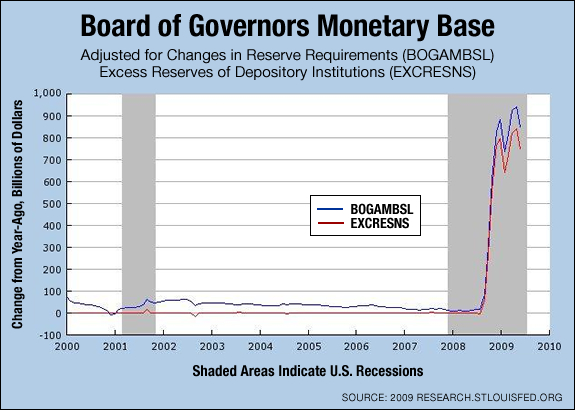

Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke has managed to make inflation hawks of us all. An unprecedented explosion of the monetary base has driven the federal-funds interest rate from 5.25 percent all the way down to 0 percent. So much money is sloshing around the system that banks are now lending to one another for free.

The chart above tells this story. An extra $1 trillion has been created out of thin air. Nothing like this has ever happened in American history — not during WWII, not in the 1970s, and not in the aftermath of 9/11.

So why no Weimarian wheelbarrow stories? Because the money is stuck in the system. The Fed makes it and sends it to the banks. Meanwhile, the banks lend a little and keep the rest in their "vaults." Why? They're afraid to lend. And they're afraid to lend because they still don't know the rules.

Will a bank fail its next "stress test"? Will it be nationalized as a result, or dismantled in disgrace? Will there be perp walks for scapegoated bank CEOs? The bankers don't know, and they don't want to find out. So they've hoarded the money, watching their reserves and capital cushions rise far above official requirements. They've built a dam.

But what happens when the floodgates open? At some point the banks will have to release a river of liquidity. Consumers are demanding it, Congress is demanding it, and even President Obama is demanding it. (That last one may well be the clincher.)

None of us knows exactly when this money flood is coming. My friend Larry Kudlow posits a long timeframe. Another friend, Forbes publisher Rich Karlgaard, says inflation will arrive about five minutes after the recovery starts. No one claims to know exactly when. But it's no longer a question of "if."

It's coming. On the supply-side, we're all inflation hawks now.

© Jerry Bowyer

July 21, 2009

Back in 2006, when the federal-funds rate peaked at 5.25 percent, several economists writing for National Review Online argued that the Federal Reserve was too tight. We also held that the gold price, which was climbing higher at the time, was not an unerring Polaris around which all other inflation indicators (such as exchange rates, nominal interest rates, and yield curves) must revolve. We wrote that the system was running the risk of too little liquidity, not too much.

One the other side of the debate, several economists writing for NRO argued that the Fed was too loose, and that it likely would be forced to raise rates. They generally predicted runaway inflation if the Fed cut rates at all within a relatively short period of time (up to two years). They predicted that long-term interest rates and mortgage rates would accordingly rise to very high levels. They believed this, largely, because of increases in the price of gold.

Buzzcharts will let open-minded observers mull over which, if any, side has been vindicated by ensuing events. We come not to shake things up, but to shake hands; not to pick a fight with our friends on the supply-side, but instead to pick a fight with our central bank.

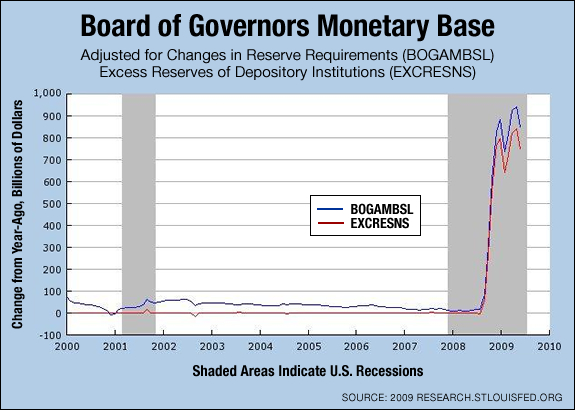

Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke has managed to make inflation hawks of us all. An unprecedented explosion of the monetary base has driven the federal-funds interest rate from 5.25 percent all the way down to 0 percent. So much money is sloshing around the system that banks are now lending to one another for free.

The chart above tells this story. An extra $1 trillion has been created out of thin air. Nothing like this has ever happened in American history — not during WWII, not in the 1970s, and not in the aftermath of 9/11.

So why no Weimarian wheelbarrow stories? Because the money is stuck in the system. The Fed makes it and sends it to the banks. Meanwhile, the banks lend a little and keep the rest in their "vaults." Why? They're afraid to lend. And they're afraid to lend because they still don't know the rules.

Will a bank fail its next "stress test"? Will it be nationalized as a result, or dismantled in disgrace? Will there be perp walks for scapegoated bank CEOs? The bankers don't know, and they don't want to find out. So they've hoarded the money, watching their reserves and capital cushions rise far above official requirements. They've built a dam.

But what happens when the floodgates open? At some point the banks will have to release a river of liquidity. Consumers are demanding it, Congress is demanding it, and even President Obama is demanding it. (That last one may well be the clincher.)

None of us knows exactly when this money flood is coming. My friend Larry Kudlow posits a long timeframe. Another friend, Forbes publisher Rich Karlgaard, says inflation will arrive about five minutes after the recovery starts. No one claims to know exactly when. But it's no longer a question of "if."

It's coming. On the supply-side, we're all inflation hawks now.

© Jerry Bowyer

The views expressed by RenewAmerica columnists are their own and do not necessarily reflect the position of RenewAmerica or its affiliates.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)