Tom O'Toole

You are Knute - - and upon this Rockne I will build "The Irish"

By Tom O'Toole

Reprinted from Fighting Irish Thomas, 3-31-07.

Reprinted on Spero News.

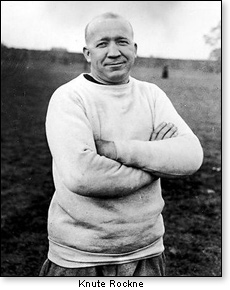

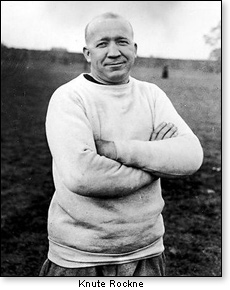

The date was 3-31-31. While there was, on that same date, an earthquake in Nicaragua that killed thousands, the Midwestern newspaper headlines (and indeed those around the world) instead centered upon a small airplane crash in Kansas that killed eight. The first seven would have died unnoticed, but the death of the last passenger (according to the United Press accounts) "shocked the entire world, and business and industry was halted ..." Within minutes, telegrams from the president of the United States, the king of Norway and heads of state from nearly every country, not to mention the presidents of colleges as well as athletes such as Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey, began arriving. Meanwhile, millions of boys wept. The eighth man on that plane was Knute Kenneth Rockne.

The date was 3-31-31. While there was, on that same date, an earthquake in Nicaragua that killed thousands, the Midwestern newspaper headlines (and indeed those around the world) instead centered upon a small airplane crash in Kansas that killed eight. The first seven would have died unnoticed, but the death of the last passenger (according to the United Press accounts) "shocked the entire world, and business and industry was halted ..." Within minutes, telegrams from the president of the United States, the king of Norway and heads of state from nearly every country, not to mention the presidents of colleges as well as athletes such as Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey, began arriving. Meanwhile, millions of boys wept. The eighth man on that plane was Knute Kenneth Rockne.

If Rockne was merely the greatest coach who ever lived (his 13-season record of 105 wins, 12 loses and 5 ties, still remains the best ever in college football) his death at forty-three would not have brought such grief, nor would his legend have been so lasting. Son of Norwegian immigrants, Rock came to America at the age of five after his father's two-wheel carry-all buggy won an award at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893. Knute learned the game of football in the rough and tumble Windy City neighborhood of Logan Square, under the watchful eye of (I'm not kidding!) "an Irish copper named O'Goole." Knute's dad Lars wasn't keen on college, so Rockne earned his way to Notre Dame (then cheaper than the University of Illinois!) by working in the mail room for five years before entering Our Lady's University, "the lone Norse Protestant invader of a Catholic stronghold," a balding broken-nosed freshman, at the age of twenty-two.

There's no doubt Rockne was a decent football player at Notre Dame — his class went 24-1-3 and he was a key component along with QB Gus Dorais of modernizing the passing game, catching half of Dorais' completions in Notre Dame's shocking 1913 35-13 rout of highly favored Army. But he was a better tactician, and even better chemist, and upon his 1914 graduation, stayed on at ND as chemistry instructor, head track coach and assistant football coach — in that order. But when the head coaching job came open, and Rockne chose it over heading the Chemistry Department, most observers thought he was crazy.

After 1918, his first season, which WWI shortened to six games (the Irish winning three, losing one and tying two) Rockne went undefeated the next two years and the Irish were crowned undisputed National Champions in 1920. Still, that was not the main story. THAT headline belonged to Rockne's shooting star George Gipp. Gipp, who like Rockne entered college late, was indifferent toward sports — and life — until he met his mentor. Under Rockne's guidance, Gipp, a superb runner, passer, and kicker (George once drop-kicked a field goal from sixty yards away) became the best player (according to Rock) ever to play at Notre Dame. Although Knute could not completely reform George; indeed Gipp continued to skip class, to earn his money hustling pool, and to party (allegedly Gipp caught the pneumonia that would kill him at the age of twenty-five sleeping off an all-night bender in the South Bend snow) Rockne and Our Lady definitely had an effect on him. Gipp, who died weeks after the 1920 season and within days of being named Notre Dame's first ever 1st Team All-American, converted to Catholicism on his death bed, and his life, early death and conversion, coupled with Rockne's own, certainly sealed the legend of Notre Dame football forever.

Rock's own conversion to Catholicism came on November 20, 1925, to the delight of his young son, Knute Jr., when he saw his dad also receive the Host during his class' First Holy Communion Mass. Rockne, describing his religion decision, stated "One night before a big game in the East, I was nervous and unable to sleep and went downstairs to the lobby. Between five and six o'clock, I saw two of my players hurrying out [of the hotel]. Within minutes, almost the whole team followed ... and I decided to go with. [While at morning Mass] they didn't realize it, but they made a powerful impression on me ... walking up to the Communion rail to receive ... the hours of sleep they had sacrificed ... I understood for the first time what a powerful ally their religion was to their work on the football field. Later I had the happiness of joining my players at the Communion rail."

Truth be told, Rockne's death was not exactly martyrdom, and he probably did not die a saint. He spent too little time with his young kids (he sent his two sons away to boarding school) and too much time on his football job and business promotions (at the time of his death, Rockne was flying to Hollywood to ink a $100,000 movie/newspaper deal). He continually embarrassed the Holy Cross Fathers of Notre Dame by seeking more lucrative jobs while under contract — Rock nearly agreed to terms with several Big 10 schools and actually signed a written contract with Columbia College in New York, needing several lawyers and confessors to extradite himself. And yet, at the time of his death, Rockne had directly (as when he let a suicidal blind man meet his team, and the man became a fan — and believer — for life) or indirectly (as when a priest tried futilely to bring a cynical ex-Catholic back to the Church, until he finally told the man of Rockne's conversion, at which time the man broke down and gave his first confession in thirty years) led many to the faith. But his tragic death at the height of his coaching powers (his last two teams were both undefeated National Champions) no doubt inspired and continues to inspire many in ways his life alone couldn't. And so on the anniversary of his death, let us not only recall the great coach, the man who revolutionized the game and put Fighting Irish football on the map. Let us also remember the humble soul who followed Gipp to the Faith and his players to the Communion rail, that we, like Rockne, realize it is Christ (and of course, Our Lady) that makes Notre Dame football special.

© Tom O'Toole

March 31, 2011

Reprinted from Fighting Irish Thomas, 3-31-07.

Reprinted on Spero News.

The date was 3-31-31. While there was, on that same date, an earthquake in Nicaragua that killed thousands, the Midwestern newspaper headlines (and indeed those around the world) instead centered upon a small airplane crash in Kansas that killed eight. The first seven would have died unnoticed, but the death of the last passenger (according to the United Press accounts) "shocked the entire world, and business and industry was halted ..." Within minutes, telegrams from the president of the United States, the king of Norway and heads of state from nearly every country, not to mention the presidents of colleges as well as athletes such as Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey, began arriving. Meanwhile, millions of boys wept. The eighth man on that plane was Knute Kenneth Rockne.

The date was 3-31-31. While there was, on that same date, an earthquake in Nicaragua that killed thousands, the Midwestern newspaper headlines (and indeed those around the world) instead centered upon a small airplane crash in Kansas that killed eight. The first seven would have died unnoticed, but the death of the last passenger (according to the United Press accounts) "shocked the entire world, and business and industry was halted ..." Within minutes, telegrams from the president of the United States, the king of Norway and heads of state from nearly every country, not to mention the presidents of colleges as well as athletes such as Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey, began arriving. Meanwhile, millions of boys wept. The eighth man on that plane was Knute Kenneth Rockne.If Rockne was merely the greatest coach who ever lived (his 13-season record of 105 wins, 12 loses and 5 ties, still remains the best ever in college football) his death at forty-three would not have brought such grief, nor would his legend have been so lasting. Son of Norwegian immigrants, Rock came to America at the age of five after his father's two-wheel carry-all buggy won an award at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893. Knute learned the game of football in the rough and tumble Windy City neighborhood of Logan Square, under the watchful eye of (I'm not kidding!) "an Irish copper named O'Goole." Knute's dad Lars wasn't keen on college, so Rockne earned his way to Notre Dame (then cheaper than the University of Illinois!) by working in the mail room for five years before entering Our Lady's University, "the lone Norse Protestant invader of a Catholic stronghold," a balding broken-nosed freshman, at the age of twenty-two.

There's no doubt Rockne was a decent football player at Notre Dame — his class went 24-1-3 and he was a key component along with QB Gus Dorais of modernizing the passing game, catching half of Dorais' completions in Notre Dame's shocking 1913 35-13 rout of highly favored Army. But he was a better tactician, and even better chemist, and upon his 1914 graduation, stayed on at ND as chemistry instructor, head track coach and assistant football coach — in that order. But when the head coaching job came open, and Rockne chose it over heading the Chemistry Department, most observers thought he was crazy.

After 1918, his first season, which WWI shortened to six games (the Irish winning three, losing one and tying two) Rockne went undefeated the next two years and the Irish were crowned undisputed National Champions in 1920. Still, that was not the main story. THAT headline belonged to Rockne's shooting star George Gipp. Gipp, who like Rockne entered college late, was indifferent toward sports — and life — until he met his mentor. Under Rockne's guidance, Gipp, a superb runner, passer, and kicker (George once drop-kicked a field goal from sixty yards away) became the best player (according to Rock) ever to play at Notre Dame. Although Knute could not completely reform George; indeed Gipp continued to skip class, to earn his money hustling pool, and to party (allegedly Gipp caught the pneumonia that would kill him at the age of twenty-five sleeping off an all-night bender in the South Bend snow) Rockne and Our Lady definitely had an effect on him. Gipp, who died weeks after the 1920 season and within days of being named Notre Dame's first ever 1st Team All-American, converted to Catholicism on his death bed, and his life, early death and conversion, coupled with Rockne's own, certainly sealed the legend of Notre Dame football forever.

Rock's own conversion to Catholicism came on November 20, 1925, to the delight of his young son, Knute Jr., when he saw his dad also receive the Host during his class' First Holy Communion Mass. Rockne, describing his religion decision, stated "One night before a big game in the East, I was nervous and unable to sleep and went downstairs to the lobby. Between five and six o'clock, I saw two of my players hurrying out [of the hotel]. Within minutes, almost the whole team followed ... and I decided to go with. [While at morning Mass] they didn't realize it, but they made a powerful impression on me ... walking up to the Communion rail to receive ... the hours of sleep they had sacrificed ... I understood for the first time what a powerful ally their religion was to their work on the football field. Later I had the happiness of joining my players at the Communion rail."

Truth be told, Rockne's death was not exactly martyrdom, and he probably did not die a saint. He spent too little time with his young kids (he sent his two sons away to boarding school) and too much time on his football job and business promotions (at the time of his death, Rockne was flying to Hollywood to ink a $100,000 movie/newspaper deal). He continually embarrassed the Holy Cross Fathers of Notre Dame by seeking more lucrative jobs while under contract — Rock nearly agreed to terms with several Big 10 schools and actually signed a written contract with Columbia College in New York, needing several lawyers and confessors to extradite himself. And yet, at the time of his death, Rockne had directly (as when he let a suicidal blind man meet his team, and the man became a fan — and believer — for life) or indirectly (as when a priest tried futilely to bring a cynical ex-Catholic back to the Church, until he finally told the man of Rockne's conversion, at which time the man broke down and gave his first confession in thirty years) led many to the faith. But his tragic death at the height of his coaching powers (his last two teams were both undefeated National Champions) no doubt inspired and continues to inspire many in ways his life alone couldn't. And so on the anniversary of his death, let us not only recall the great coach, the man who revolutionized the game and put Fighting Irish football on the map. Let us also remember the humble soul who followed Gipp to the Faith and his players to the Communion rail, that we, like Rockne, realize it is Christ (and of course, Our Lady) that makes Notre Dame football special.

© Tom O'Toole

The views expressed by RenewAmerica columnists are their own and do not necessarily reflect the position of RenewAmerica or its affiliates.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)