Tom O'Toole

The Pilgrim's Regress: Rembert's disordered "Weak-land" revisited

By Tom O'Toole

Originally published in Culture Wars, May 2010, Vol. 29, No. 6

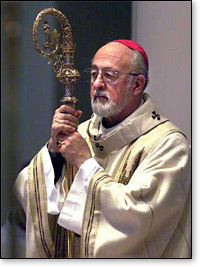

[A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop, Rembert G. Weakland, OSB William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, 2009.] Although my book reviews are far from infallible, one does not have to be a member of the Magisterium (or even a Notre Dame alumnus) to realize that when the first person to praise your memoirs is the lyin' liberal press' favorite sound-bite machine, Fr. McBrien, that this is not going to be the spiritually enriching autobiography of a future saint. Furthermore, when the author himself, a self-described dissident homosexual archbishop, tells you that a pope who is up for sainthood could barely stand the sight of him, the orthodox Catholic reader has pretty much dismissed A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church as his book of the month club selection. But while Pilgrim may be a popular choice for the "The Church needs married and woman (and gay) priests!" crowd, there is compelling reason for the faithful to read it too; for as a major player in the often faulty implementation of Vatican II, Weakland gives us a bird's-eye view of what went wrong — and exactly how "the smoke of Satan" entered the Church.

[A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop, Rembert G. Weakland, OSB William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, 2009.] Although my book reviews are far from infallible, one does not have to be a member of the Magisterium (or even a Notre Dame alumnus) to realize that when the first person to praise your memoirs is the lyin' liberal press' favorite sound-bite machine, Fr. McBrien, that this is not going to be the spiritually enriching autobiography of a future saint. Furthermore, when the author himself, a self-described dissident homosexual archbishop, tells you that a pope who is up for sainthood could barely stand the sight of him, the orthodox Catholic reader has pretty much dismissed A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church as his book of the month club selection. But while Pilgrim may be a popular choice for the "The Church needs married and woman (and gay) priests!" crowd, there is compelling reason for the faithful to read it too; for as a major player in the often faulty implementation of Vatican II, Weakland gives us a bird's-eye view of what went wrong — and exactly how "the smoke of Satan" entered the Church.

In his review for his Providence, Rhode Island, newspaper, Bishop Thomas J. Tobin, describes Pilgrim as "an intriguing combination of theology and gossip, Aquinas and Oprah," and it doesn't take long to see what he means. After opening his autobiography with a self-righteous public confession of his sinful homosexual fling with Paul Marcoux (and the huge "hush money" scandal that surrounded it), Rembert returns to the beginning, his birth and childhood in Patton, Pennsylvania. It starts out as your typical large-Catholic-family tragedy inspirational depression era saga, although dissidence is never far from the surface. After losing his fortune in the financial crisis, George's father (George was Weakland's baptismal name; Rembert the name given him when he became an abbot) Basil "spent much time with his friends in the...unheated rooms...drinking and lamenting...he died [of] pneumonia the day before his thirty-fifth birthday and the day after my fifth, leaving a wife and six children, the oldest nine, the youngest six months" (pg 24). But George's mother, Mary, vowed to keep her kids together, and despite few funds, scant food and little heat, the faith in this close-knit family helped them not only to survive, but thrive.

Whether Weakland learned his same-sex attraction during childhood is debatable, there's little doubt his penchant for disagreeing with Church teaching was. Weakland's lament, "that much of my life was spent seeking the father figure that had been there so briefly" (pg 26), may be a factor in some of his illicit adult relationships, to his depiction of his mother as "a woman of deep faith," but with "an independent mind with regard to some positions the Church took" (pg 32), certainly shows the roots of his own dissidence. Later, when George became attracted to the priesthood, he was sent away after the eighth grade to St. Vincent Prep School (Latrobe, PA) to continue his studies. However, when he returned that summer and told his mother the disturbing story of a priest who had been dismissed from St. Vincent after sexually molesting several students, "she surprised me with one remark; 'Well, I hope your own first sexual experiences will be beautiful and the outcome of deep love.' On reflection, I think she was saying something that I had not fully grasped; [but] I did not have the vocabulary or the courage then to talk to her about homosexuality" (pgs 46-47).

If the almost complete absence of teaching about human sexuality (either normal or disordered) at the seminary must sadly be excused as part of the culture of the day, the dissident teaching that went on in St. Vincent certainly cannot. Unsure of himself, and still frightened of the sexual abuse that happened to his classmates, Weakland vowed to avoid "the sewing circle" crowd and submerged "any homosexual desires as deeply as I could" (pg 46). Weakland, always a top-notch student, did well in the studies of Latin, Greek, Science, and English Literature, but proved even more gifted at music, and was eventually sent to Julliard to complete advanced studies in piano. Still, as well rounded as this education was, sound theology apparently was not always a part of it. "During Lent," recalls Weakland, "the ordained monks all spent long hours in the confessional. Questions about contraception [were] raised...most of us were reluctant to recommend the rhythm method since we had seen many instances when it did not work ...and it seemed dishonest since the intention of preventing pregnancy was the same as if artificial means were used. We advised penitents to look carefully at the Church's teaching, then decide in their own consciences what...was right. We had been instructed that the [layperson's] individual conscience should be respected" (pg 92).

Having mastered this democratic, conscience-is-king tabloid version of Catholicism, Weakland quickly rose through the Monastic ranks, first becoming archabbot of St. Vincent's in 1963, consulter to the Consilium on liturgical music changes due to Vatican II in 1964, and lastly, the abbot primate of the entire Benedictine Order in 1967. It was as abbot primate that Weakland became a frequent and influential visitor of Pope Paul VI. Recounting these meetings, Weakland confirms what conservatives long feared; that Paul, in an attempt to befriend everyone (the pope often prepared several "Benedictine trivia" questions for Weakland before they got down to business!) allowed his young liberal advisors far too much leeway in setting the post Vatican II agenda before he attempted to curb Pandora's box of relativism he had created. "Instead of giving into one side or the other, Paul tried to keep peace by creating parallel bodies [of] conservative and forward-looking cardinals... to avoid schism in the Church. His fear, coupled with an innate wish not to offend anyone...alienated his most loyal supporters and collaborators" (pg 220). In the end, Weakland's analysis that Paul's personal views shifted is incorrect; his issuing of Humanae Vitae was a courageous stand against the Modernist mob, not a "cave in" to conservatives as Weakland suggests. Still, if Paul realized (too late) that "The smoke of Satan has entered the temple of God" (from the pope's famous 1972 homily), Paul did not grasp the perhaps even greater firestorm he created by appointing Weakland (and several of his less-than-orthodox contemporaries) bishop shortly before his death.

Unlike a monk, Weakland realized a bishop is called upon to make statements on doctrine, and the new archbishop of Milwaukee wasted no time in issuing outrageous statements on everything from women's ordination to the practicing homosexual's right to worship. Quick to grasp the situation, John Paul's visits with Weakland were anything but trivial. "On every ad limina visit without exception," says Weakland, "I would be singled out to meet with Cardinal Baggio (later Cardinal Bernadin Gantin and toward the end of his tenure Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) where I would be presented with a list of complaints" (pg 264). The meetings with John Paul himself (as depicted in the opening quote) were rather quick and to the point, as John Paul did not waste much time on fools, or at least bishops who were fooling themselves. It is interesting to note their different take on these meetings; Weakland depicting "a professor... snidely correcting a less than gifted student" (pg 307), while John Paul recalling (in his book Rise, Let Us Be On Our Way) [here] there can be no turning one's back upon the truth...no room for compromise to human diplomacy." I suppose it is the difference of one who began his bishopric with a pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa, and ended with the people proclaiming him "The Great" saint, and another who began his tenure with a gay affair and ended his ministry by resigning in disgrace because of it.

While I agree with Bishop Tobin's review that we should not overlook Weakland's many redeeming qualities (for example, his fight to bring the vernacular of the Divine Office to some Benedictine sisters who didn't understand Latin over the protest of the abbess who declared, "They don't need to understand the prayers since God does!" seems commendable), Tobin's observation that the book is filled with "self-serving inconsistencies and contradictions" cannot be ignored either. To name just a few, Weakland is quick to point out in the quoted passage that the rhythm method taught in the fifties wasn't so reliable, but fails to mention that the Billings Method taught today is, or that Church teaching (from his favorite, Humanae Vitae) shows that natural family planning maintains the bond between the unitive and the procreative, whereas contraception does not. Later, he depicts John Paul as "beyond doubt, a holy man, worthy of being officially recognized by the Church," but then flippantly refers to JP's reign as "that overly long...burdensome pontificate" (pg 402), despite having just finished writing that his bout with prostate cancer gave "me a growing empathy for the sick" (pg 380). And finally, Weakland claims to have decided to pay the $450,000 "hush money" to quiet his gay affair because the Vatican advised him that would keep the Church from scandal, but in doctrinal matters, Weakland rarely listened to Rome, and seemed to revel in the scandal that his heretical statements caused.

Thus if Weakland's story does to a large extent truthfully (if unwittingly) depict the faulty seminary training of the 40s and 50s, the improper implementation of Vatican II in the 60s and 70s, and slow and often misguided response to the priest sex scandal of the 80s, 90s and early 2000s, Weakland seems incapable of grasping eternal truths concerning his own soul. Since the book's release, Weakland has admitted to several other homosexual affairs, bragging to Laurie Goldstein of The New York Post that he was the first bishop to come out of the closet," adding, "How can [the Church] tell 400 million gays that you have to pass your whole life without any physical genital expressions of love!" If Pilgrim has proved the need for the Church's further definitions on married sexuality and the priestly celibacy, Weakland's retirement rants have shown the need for further definition of the nature of homosexuality beyond the Catechism's, "Its psychological genesis remains largely unexplained" (CCC 2357). For if it is largely learned, it can then be unlearned, but if it is mostly innate (as Weakland believes and the Catechism's, "They do not choose their homosexual condition..." does not condemn), then a different strategy to keep gays from giving in to these "intrinsically disordered acts" (CCC 2357) must be developed, because to witness this retired bishop reduced to a dirty old man, preaching "grave depravity" as true love is beyond sad. Let us pray that if Rembert does not repent, he at least resigns his title of bishop, so that no further faithful are lost due to his reprehensible rhetoric.

© Tom O'Toole

September 5, 2010

Originally published in Culture Wars, May 2010, Vol. 29, No. 6

-

"...All readers will be moved by this honest, riveting, and exceedingly well-written story of frustration and hope, sin and redemption..." — Notre Dame's Father Richard P. McBrien, from the book's jacket cover.

"As I was leaving [Pope John Paul II] suddenly asked me out of thin air: 'How old are you now?' When I replied 'Seventy-one,' he did not look me in the eye but, with bowed head and expressionless face gave a low, indistinct grumble. I interpreted it...as a way of saying, 'I guess I still have to tolerate you for four more years' — Archbishop Weakland, after his last ad limina visit to the Pope (Pilgrim, pg 389).

[A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop, Rembert G. Weakland, OSB William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, 2009.] Although my book reviews are far from infallible, one does not have to be a member of the Magisterium (or even a Notre Dame alumnus) to realize that when the first person to praise your memoirs is the lyin' liberal press' favorite sound-bite machine, Fr. McBrien, that this is not going to be the spiritually enriching autobiography of a future saint. Furthermore, when the author himself, a self-described dissident homosexual archbishop, tells you that a pope who is up for sainthood could barely stand the sight of him, the orthodox Catholic reader has pretty much dismissed A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church as his book of the month club selection. But while Pilgrim may be a popular choice for the "The Church needs married and woman (and gay) priests!" crowd, there is compelling reason for the faithful to read it too; for as a major player in the often faulty implementation of Vatican II, Weakland gives us a bird's-eye view of what went wrong — and exactly how "the smoke of Satan" entered the Church.

[A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church: Memoirs of a Catholic Archbishop, Rembert G. Weakland, OSB William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, 2009.] Although my book reviews are far from infallible, one does not have to be a member of the Magisterium (or even a Notre Dame alumnus) to realize that when the first person to praise your memoirs is the lyin' liberal press' favorite sound-bite machine, Fr. McBrien, that this is not going to be the spiritually enriching autobiography of a future saint. Furthermore, when the author himself, a self-described dissident homosexual archbishop, tells you that a pope who is up for sainthood could barely stand the sight of him, the orthodox Catholic reader has pretty much dismissed A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church as his book of the month club selection. But while Pilgrim may be a popular choice for the "The Church needs married and woman (and gay) priests!" crowd, there is compelling reason for the faithful to read it too; for as a major player in the often faulty implementation of Vatican II, Weakland gives us a bird's-eye view of what went wrong — and exactly how "the smoke of Satan" entered the Church.In his review for his Providence, Rhode Island, newspaper, Bishop Thomas J. Tobin, describes Pilgrim as "an intriguing combination of theology and gossip, Aquinas and Oprah," and it doesn't take long to see what he means. After opening his autobiography with a self-righteous public confession of his sinful homosexual fling with Paul Marcoux (and the huge "hush money" scandal that surrounded it), Rembert returns to the beginning, his birth and childhood in Patton, Pennsylvania. It starts out as your typical large-Catholic-family tragedy inspirational depression era saga, although dissidence is never far from the surface. After losing his fortune in the financial crisis, George's father (George was Weakland's baptismal name; Rembert the name given him when he became an abbot) Basil "spent much time with his friends in the...unheated rooms...drinking and lamenting...he died [of] pneumonia the day before his thirty-fifth birthday and the day after my fifth, leaving a wife and six children, the oldest nine, the youngest six months" (pg 24). But George's mother, Mary, vowed to keep her kids together, and despite few funds, scant food and little heat, the faith in this close-knit family helped them not only to survive, but thrive.

Whether Weakland learned his same-sex attraction during childhood is debatable, there's little doubt his penchant for disagreeing with Church teaching was. Weakland's lament, "that much of my life was spent seeking the father figure that had been there so briefly" (pg 26), may be a factor in some of his illicit adult relationships, to his depiction of his mother as "a woman of deep faith," but with "an independent mind with regard to some positions the Church took" (pg 32), certainly shows the roots of his own dissidence. Later, when George became attracted to the priesthood, he was sent away after the eighth grade to St. Vincent Prep School (Latrobe, PA) to continue his studies. However, when he returned that summer and told his mother the disturbing story of a priest who had been dismissed from St. Vincent after sexually molesting several students, "she surprised me with one remark; 'Well, I hope your own first sexual experiences will be beautiful and the outcome of deep love.' On reflection, I think she was saying something that I had not fully grasped; [but] I did not have the vocabulary or the courage then to talk to her about homosexuality" (pgs 46-47).

If the almost complete absence of teaching about human sexuality (either normal or disordered) at the seminary must sadly be excused as part of the culture of the day, the dissident teaching that went on in St. Vincent certainly cannot. Unsure of himself, and still frightened of the sexual abuse that happened to his classmates, Weakland vowed to avoid "the sewing circle" crowd and submerged "any homosexual desires as deeply as I could" (pg 46). Weakland, always a top-notch student, did well in the studies of Latin, Greek, Science, and English Literature, but proved even more gifted at music, and was eventually sent to Julliard to complete advanced studies in piano. Still, as well rounded as this education was, sound theology apparently was not always a part of it. "During Lent," recalls Weakland, "the ordained monks all spent long hours in the confessional. Questions about contraception [were] raised...most of us were reluctant to recommend the rhythm method since we had seen many instances when it did not work ...and it seemed dishonest since the intention of preventing pregnancy was the same as if artificial means were used. We advised penitents to look carefully at the Church's teaching, then decide in their own consciences what...was right. We had been instructed that the [layperson's] individual conscience should be respected" (pg 92).

Having mastered this democratic, conscience-is-king tabloid version of Catholicism, Weakland quickly rose through the Monastic ranks, first becoming archabbot of St. Vincent's in 1963, consulter to the Consilium on liturgical music changes due to Vatican II in 1964, and lastly, the abbot primate of the entire Benedictine Order in 1967. It was as abbot primate that Weakland became a frequent and influential visitor of Pope Paul VI. Recounting these meetings, Weakland confirms what conservatives long feared; that Paul, in an attempt to befriend everyone (the pope often prepared several "Benedictine trivia" questions for Weakland before they got down to business!) allowed his young liberal advisors far too much leeway in setting the post Vatican II agenda before he attempted to curb Pandora's box of relativism he had created. "Instead of giving into one side or the other, Paul tried to keep peace by creating parallel bodies [of] conservative and forward-looking cardinals... to avoid schism in the Church. His fear, coupled with an innate wish not to offend anyone...alienated his most loyal supporters and collaborators" (pg 220). In the end, Weakland's analysis that Paul's personal views shifted is incorrect; his issuing of Humanae Vitae was a courageous stand against the Modernist mob, not a "cave in" to conservatives as Weakland suggests. Still, if Paul realized (too late) that "The smoke of Satan has entered the temple of God" (from the pope's famous 1972 homily), Paul did not grasp the perhaps even greater firestorm he created by appointing Weakland (and several of his less-than-orthodox contemporaries) bishop shortly before his death.

Unlike a monk, Weakland realized a bishop is called upon to make statements on doctrine, and the new archbishop of Milwaukee wasted no time in issuing outrageous statements on everything from women's ordination to the practicing homosexual's right to worship. Quick to grasp the situation, John Paul's visits with Weakland were anything but trivial. "On every ad limina visit without exception," says Weakland, "I would be singled out to meet with Cardinal Baggio (later Cardinal Bernadin Gantin and toward the end of his tenure Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) where I would be presented with a list of complaints" (pg 264). The meetings with John Paul himself (as depicted in the opening quote) were rather quick and to the point, as John Paul did not waste much time on fools, or at least bishops who were fooling themselves. It is interesting to note their different take on these meetings; Weakland depicting "a professor... snidely correcting a less than gifted student" (pg 307), while John Paul recalling (in his book Rise, Let Us Be On Our Way) [here] there can be no turning one's back upon the truth...no room for compromise to human diplomacy." I suppose it is the difference of one who began his bishopric with a pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa, and ended with the people proclaiming him "The Great" saint, and another who began his tenure with a gay affair and ended his ministry by resigning in disgrace because of it.

While I agree with Bishop Tobin's review that we should not overlook Weakland's many redeeming qualities (for example, his fight to bring the vernacular of the Divine Office to some Benedictine sisters who didn't understand Latin over the protest of the abbess who declared, "They don't need to understand the prayers since God does!" seems commendable), Tobin's observation that the book is filled with "self-serving inconsistencies and contradictions" cannot be ignored either. To name just a few, Weakland is quick to point out in the quoted passage that the rhythm method taught in the fifties wasn't so reliable, but fails to mention that the Billings Method taught today is, or that Church teaching (from his favorite, Humanae Vitae) shows that natural family planning maintains the bond between the unitive and the procreative, whereas contraception does not. Later, he depicts John Paul as "beyond doubt, a holy man, worthy of being officially recognized by the Church," but then flippantly refers to JP's reign as "that overly long...burdensome pontificate" (pg 402), despite having just finished writing that his bout with prostate cancer gave "me a growing empathy for the sick" (pg 380). And finally, Weakland claims to have decided to pay the $450,000 "hush money" to quiet his gay affair because the Vatican advised him that would keep the Church from scandal, but in doctrinal matters, Weakland rarely listened to Rome, and seemed to revel in the scandal that his heretical statements caused.

Thus if Weakland's story does to a large extent truthfully (if unwittingly) depict the faulty seminary training of the 40s and 50s, the improper implementation of Vatican II in the 60s and 70s, and slow and often misguided response to the priest sex scandal of the 80s, 90s and early 2000s, Weakland seems incapable of grasping eternal truths concerning his own soul. Since the book's release, Weakland has admitted to several other homosexual affairs, bragging to Laurie Goldstein of The New York Post that he was the first bishop to come out of the closet," adding, "How can [the Church] tell 400 million gays that you have to pass your whole life without any physical genital expressions of love!" If Pilgrim has proved the need for the Church's further definitions on married sexuality and the priestly celibacy, Weakland's retirement rants have shown the need for further definition of the nature of homosexuality beyond the Catechism's, "Its psychological genesis remains largely unexplained" (CCC 2357). For if it is largely learned, it can then be unlearned, but if it is mostly innate (as Weakland believes and the Catechism's, "They do not choose their homosexual condition..." does not condemn), then a different strategy to keep gays from giving in to these "intrinsically disordered acts" (CCC 2357) must be developed, because to witness this retired bishop reduced to a dirty old man, preaching "grave depravity" as true love is beyond sad. Let us pray that if Rembert does not repent, he at least resigns his title of bishop, so that no further faithful are lost due to his reprehensible rhetoric.

© Tom O'Toole

The views expressed by RenewAmerica columnists are their own and do not necessarily reflect the position of RenewAmerica or its affiliates.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)