Frank Maguire

Can religious and political dogma conflict with truth and justice?

Part One

By Frank Maguire

"Acquitting the guilty and condemning the innocent — the Lord detests them both." Proverbs 17:15

"It is not good to be partial to the wicked or to deprive the innocent of justice." Proverbs 18:5

Recently I watched an episode of "Law and Order," a skillfully done series that employs the talents of good writers, sensitive directors, and actors who know their profession. This particular instalment inspired me to closer than usual attention and more than perfunctory consideration.

Recently I watched an episode of "Law and Order," a skillfully done series that employs the talents of good writers, sensitive directors, and actors who know their profession. This particular instalment inspired me to closer than usual attention and more than perfunctory consideration.

In three segments I will offer some thoughts on what has turned careful deliberation into chaotic debilitation in America's religious and judicial institutions. What has, in my opinion, enfeebled America in its foundations of justice under the law and the Judaeo/Christian pursuit of justice through the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. How Truth and Justice have been bifurcated and corrupted by political, academic, ecclesiastical pride and egoistic ambition.

The story I relate presents a profound conflict in the conscience of a Roman Catholic parish priest who is asked by a parishioner to attend to her son who appears to have something troubling his conscience. The conscientiously devoted "good Father" comforts the woman and promises to speak with the young man.

In summary, a young man is attacked and beaten by a mob. During the beating, he is stabbed to death by one of the assailants. Based upon circumstantial evidence, one of the attackers is arrested, tried, and convicted, receiving a life sentence. During the trial and the subsequent imprisonment, the convicted man insists that he is not guilty of the killing.

The priest meets privately with the woman's son, but not in the manner of the confessional — i.e., not sacramentally — and he admits that he is guilty of the murder. The priest tells him that his responsibility is to surrender to the police and to let the justice system employ. He tells the priest that he will not do that. The priest divulges the confession to no one, mistakenly equating personal counseling with the sacrament of Penance.

The conflict of consciences and the intricacy of the laws begin when a witness to the killing tells the police that the convicted man was not the killer and further implicates the young man whom the priest counseled.

A violent event occurs that aggravates matters. A priest is shot to death as he is hearing confessions. He had been serving the same parish as the counselor priest. The police investigation uncovers the fact that the murdered priest was actually asked by the counselor priest to substitute for him in the confessional on the day of the murder.

The police question the substituted-for priest. During the questioning, they ask him if he knew the young man who had been murdered by the gang and if he knows the man who was convicted. They also ask if he knows the man who has been alleged to have been the actual killer. He confirms that all three men had been parishioners, all familiar to him.

The police question the substituted-for priest. During the questioning, they ask him if he knew the young man who had been murdered by the gang and if he knows the man who was convicted. They also ask if he knows the man who has been alleged to have been the actual killer. He confirms that all three men had been parishioners, all familiar to him.

In further questioning, the priest tells the police of his counseling of the man now suspected of being the killer in the mob violence. When the police ask the priest to tell them what the suspect told him, he refuses based on his oath taken regarding the privileged sanctity of the confessional.

The police ask where the counseling took place. The priest says that it was in the home of the suspect. The priest is asked if the young man had asked for forgiveness, showed repentance, and had the priest given him absolution. The priest answers "No."

The police cite cases similar and explain to the priest that the law demands that he testify as to what he had been told — that the personal counseling was not equivalent to the actual sacrament of penance in this case. The priest is unwilling to acknowledge the distinction and still refuses to divulge that which he had been told. He did tell the police that his counseling had involved telling the counseled that it was his responsibility to turn himself in to the police and allow the law to pursue justice.

The police reveal that because a witness has come forth implicating him, the woman's son has been questioned about the stabbing; and because he had not known the confession schedule had been changed, he is also a suspect in the shooting.

After hearing the counsel the priest had given the now suspect, the police suggest that he was very likely the actual target because he alone knew what had actually happened. They ask the priest that if the man he counseled killed his replacement, does it not indicate that the confessed killer is unrepentant for his first homicide? And, was it the intention to murder him because he might testify if the matter went before the law?

Even with the conflicted conscience, the priest refuses to assent to the de jure distinction claimed by the district attorney, and that he still chooses to act in fides et fiducia, "by faith and confidence," in his understanding of the oath he has taken to God regarding the sanctity of the sacrament of confession.

When the bishop and the See's attorney plead the priest's and the church's position, the district attorney insists that since an innocent man is imprisoned for life unless the conviction is justly overturned, that his own oath of office — to pursue truth and justice through the law — requires that he subpoena the priest to testify in court.

Still, the priest objects, telling the district attorney that he is fervently praying that the suspect will be eventually guided by the Spirit of the Lord to confess his guilt first to God — thus obtaining absolution for his sin — and subsequently to the law to accept the judicial consequences.

The oaths taken by the priest and by the district attorney are still conflicted, amounting to an argumentum ad lex sacramentalis...an argument as to the priority (a priori) of "purgation by oath." That is, are truth and justice best served by acknowledging the best interests of the citizenry as a whole — does the need for the security of every citizen of the State take priority over the personal spiritual needs of persons who are though answerable in their Faith also answerable to the laws of the State?

The priest continues to maintain that if he breaks his oath, he will have to remove himself from the priesthood, since he cannot be trusted by sinners who want to confess to him in the protected secrecy of the confessional.

After much grievous soul-searching, the priest makes the decision to acquiescence, to testify and to surrender his priestly office.

End of Part One

******************************************************************

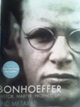

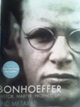

"It is impossible to understand (Dietrich) Bonhoeffer's Nachfolge (die) i.e., "succession; sequence; imitation, emulation" without becoming acquainted with the shocking capitulation of the German church to Hitler.... The answer is that the true gospel, summed-up by Bonhoeffer as costly grace, had been lost. On the one hand, the church had become marked by formalism. That meant going to church and hearing that God just loves and forgives everyone, so it really doesn't matter much how you live. Bonhoeffer called this cheap grace. On the other hand, there was legalism, or salvation by law and good works. Legalism means that God loves you because you have pulled yourself together and are trying to live a good, disciplined life.... "But as one, Germany had lost hold of the brilliant balance Martin Luther had so persistently expounded — 'We are saved by faith alone but not by faith which is alone.'" That is, we are saved, not by anything we do, but by grace. Yet if we have truly understood and believed the gospel, it will change what we do and how we live." Timothy J. Keller, foreword to Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy by Ric Metaxas

"It is impossible to understand (Dietrich) Bonhoeffer's Nachfolge (die) i.e., "succession; sequence; imitation, emulation" without becoming acquainted with the shocking capitulation of the German church to Hitler.... The answer is that the true gospel, summed-up by Bonhoeffer as costly grace, had been lost. On the one hand, the church had become marked by formalism. That meant going to church and hearing that God just loves and forgives everyone, so it really doesn't matter much how you live. Bonhoeffer called this cheap grace. On the other hand, there was legalism, or salvation by law and good works. Legalism means that God loves you because you have pulled yourself together and are trying to live a good, disciplined life.... "But as one, Germany had lost hold of the brilliant balance Martin Luther had so persistently expounded — 'We are saved by faith alone but not by faith which is alone.'" That is, we are saved, not by anything we do, but by grace. Yet if we have truly understood and believed the gospel, it will change what we do and how we live." Timothy J. Keller, foreword to Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy by Ric Metaxas

© Frank Maguire

June 17, 2011

"Acquitting the guilty and condemning the innocent — the Lord detests them both." Proverbs 17:15

"It is not good to be partial to the wicked or to deprive the innocent of justice." Proverbs 18:5

Recently I watched an episode of "Law and Order," a skillfully done series that employs the talents of good writers, sensitive directors, and actors who know their profession. This particular instalment inspired me to closer than usual attention and more than perfunctory consideration.

Recently I watched an episode of "Law and Order," a skillfully done series that employs the talents of good writers, sensitive directors, and actors who know their profession. This particular instalment inspired me to closer than usual attention and more than perfunctory consideration.In three segments I will offer some thoughts on what has turned careful deliberation into chaotic debilitation in America's religious and judicial institutions. What has, in my opinion, enfeebled America in its foundations of justice under the law and the Judaeo/Christian pursuit of justice through the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. How Truth and Justice have been bifurcated and corrupted by political, academic, ecclesiastical pride and egoistic ambition.

The story I relate presents a profound conflict in the conscience of a Roman Catholic parish priest who is asked by a parishioner to attend to her son who appears to have something troubling his conscience. The conscientiously devoted "good Father" comforts the woman and promises to speak with the young man.

In summary, a young man is attacked and beaten by a mob. During the beating, he is stabbed to death by one of the assailants. Based upon circumstantial evidence, one of the attackers is arrested, tried, and convicted, receiving a life sentence. During the trial and the subsequent imprisonment, the convicted man insists that he is not guilty of the killing.

The priest meets privately with the woman's son, but not in the manner of the confessional — i.e., not sacramentally — and he admits that he is guilty of the murder. The priest tells him that his responsibility is to surrender to the police and to let the justice system employ. He tells the priest that he will not do that. The priest divulges the confession to no one, mistakenly equating personal counseling with the sacrament of Penance.

The conflict of consciences and the intricacy of the laws begin when a witness to the killing tells the police that the convicted man was not the killer and further implicates the young man whom the priest counseled.

A violent event occurs that aggravates matters. A priest is shot to death as he is hearing confessions. He had been serving the same parish as the counselor priest. The police investigation uncovers the fact that the murdered priest was actually asked by the counselor priest to substitute for him in the confessional on the day of the murder.

The police question the substituted-for priest. During the questioning, they ask him if he knew the young man who had been murdered by the gang and if he knows the man who was convicted. They also ask if he knows the man who has been alleged to have been the actual killer. He confirms that all three men had been parishioners, all familiar to him.

The police question the substituted-for priest. During the questioning, they ask him if he knew the young man who had been murdered by the gang and if he knows the man who was convicted. They also ask if he knows the man who has been alleged to have been the actual killer. He confirms that all three men had been parishioners, all familiar to him.In further questioning, the priest tells the police of his counseling of the man now suspected of being the killer in the mob violence. When the police ask the priest to tell them what the suspect told him, he refuses based on his oath taken regarding the privileged sanctity of the confessional.

The police ask where the counseling took place. The priest says that it was in the home of the suspect. The priest is asked if the young man had asked for forgiveness, showed repentance, and had the priest given him absolution. The priest answers "No."

The police cite cases similar and explain to the priest that the law demands that he testify as to what he had been told — that the personal counseling was not equivalent to the actual sacrament of penance in this case. The priest is unwilling to acknowledge the distinction and still refuses to divulge that which he had been told. He did tell the police that his counseling had involved telling the counseled that it was his responsibility to turn himself in to the police and allow the law to pursue justice.

The police reveal that because a witness has come forth implicating him, the woman's son has been questioned about the stabbing; and because he had not known the confession schedule had been changed, he is also a suspect in the shooting.

After hearing the counsel the priest had given the now suspect, the police suggest that he was very likely the actual target because he alone knew what had actually happened. They ask the priest that if the man he counseled killed his replacement, does it not indicate that the confessed killer is unrepentant for his first homicide? And, was it the intention to murder him because he might testify if the matter went before the law?

Even with the conflicted conscience, the priest refuses to assent to the de jure distinction claimed by the district attorney, and that he still chooses to act in fides et fiducia, "by faith and confidence," in his understanding of the oath he has taken to God regarding the sanctity of the sacrament of confession.

When the bishop and the See's attorney plead the priest's and the church's position, the district attorney insists that since an innocent man is imprisoned for life unless the conviction is justly overturned, that his own oath of office — to pursue truth and justice through the law — requires that he subpoena the priest to testify in court.

Still, the priest objects, telling the district attorney that he is fervently praying that the suspect will be eventually guided by the Spirit of the Lord to confess his guilt first to God — thus obtaining absolution for his sin — and subsequently to the law to accept the judicial consequences.

The oaths taken by the priest and by the district attorney are still conflicted, amounting to an argumentum ad lex sacramentalis...an argument as to the priority (a priori) of "purgation by oath." That is, are truth and justice best served by acknowledging the best interests of the citizenry as a whole — does the need for the security of every citizen of the State take priority over the personal spiritual needs of persons who are though answerable in their Faith also answerable to the laws of the State?

The priest continues to maintain that if he breaks his oath, he will have to remove himself from the priesthood, since he cannot be trusted by sinners who want to confess to him in the protected secrecy of the confessional.

After much grievous soul-searching, the priest makes the decision to acquiescence, to testify and to surrender his priestly office.

End of Part One

******************************************************************

-

Why has this Law and Order episode caused me such circumspect deliberation — such a careful consideration of all the relevant circumstances and possible consequences? I'll try to explain, which requires a bit of personal history.

I was born into a Roman Catholic family in Dorchester, MA, just south of metropolitan Boston. I went to a local public school and from the fifth through eighth grades to St. Matthew's School, where I was taught by the Sisters of St. Joseph. As was customarily true, the Catholic schools were more academically advanced than the typical public school and they provided religious teaching.

At St. Matthew's I received a basic understanding of fundamental Christian doctrine. Simultaneously, I was apprised of Catholic interpretation of Scripture, which I call dogmatism — i.e., that which is added to the fundaments of Scripture.

I say "added to" because the denominational segmenting of the Body of Christ is sometimes a result of interpretive "additions" to Scriptural fundamentals. Some are inconsequential, but some are major enough that accusations of "heretic," "apostate," and "cultist" are dispensed with rancor.

I am certain that all defenders of their particular denominational "interpretations" will claim that their "inspired" elucidation is correct. But, I have to ask, can all interpretation be correct? I'm not being critical of any denomination so long as they don't delete or literarily modify the Christian fundaments in order to accommodate their interpretations.

I will write more on what truth and justice mean in a culture that has become nihilistic and moral-relativist...ingredients of post-modernism that holds Truth to be solipsistic and situational — a virtual cultural-autism only sustainable when controlled by an autocratic clique.

In Part Two I will present my position on "the faith once delivered." Here, I offer resources that readers who are interested can examine in advance: http://www.moravian.org/believe/covenant_christian_living.pdf ; and Heresies: Heresy and Orthodoxy in the History of the Church, by Harold O. J. Brown, Hendrickson Publishers (1984)

"All virtue is summed up in dealing justly." Artistotle, Nichomachean Ethics (4th century B.C.)

"Injustice in this world is not something comparative; the wrong is deep, clear, and absolute in each private fate." George Santayana, "Little Essays" (1920)

"It is impossible to understand (Dietrich) Bonhoeffer's Nachfolge (die) i.e., "succession; sequence; imitation, emulation" without becoming acquainted with the shocking capitulation of the German church to Hitler.... The answer is that the true gospel, summed-up by Bonhoeffer as costly grace, had been lost. On the one hand, the church had become marked by formalism. That meant going to church and hearing that God just loves and forgives everyone, so it really doesn't matter much how you live. Bonhoeffer called this cheap grace. On the other hand, there was legalism, or salvation by law and good works. Legalism means that God loves you because you have pulled yourself together and are trying to live a good, disciplined life.... "But as one, Germany had lost hold of the brilliant balance Martin Luther had so persistently expounded — 'We are saved by faith alone but not by faith which is alone.'" That is, we are saved, not by anything we do, but by grace. Yet if we have truly understood and believed the gospel, it will change what we do and how we live." Timothy J. Keller, foreword to Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy by Ric Metaxas

"It is impossible to understand (Dietrich) Bonhoeffer's Nachfolge (die) i.e., "succession; sequence; imitation, emulation" without becoming acquainted with the shocking capitulation of the German church to Hitler.... The answer is that the true gospel, summed-up by Bonhoeffer as costly grace, had been lost. On the one hand, the church had become marked by formalism. That meant going to church and hearing that God just loves and forgives everyone, so it really doesn't matter much how you live. Bonhoeffer called this cheap grace. On the other hand, there was legalism, or salvation by law and good works. Legalism means that God loves you because you have pulled yourself together and are trying to live a good, disciplined life.... "But as one, Germany had lost hold of the brilliant balance Martin Luther had so persistently expounded — 'We are saved by faith alone but not by faith which is alone.'" That is, we are saved, not by anything we do, but by grace. Yet if we have truly understood and believed the gospel, it will change what we do and how we live." Timothy J. Keller, foreword to Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy by Ric Metaxas© Frank Maguire

The views expressed by RenewAmerica columnists are their own and do not necessarily reflect the position of RenewAmerica or its affiliates.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)