Demagoguery and deception in Tampa

Stephen Stone, RA President

One valid definition of "demagoguery" is the intentional use of emotion to sway people's thinking.

One valid definition of "demagoguery" is the intentional use of emotion to sway people's thinking.

Suppose a speaker wants to convince an unsympathetic audience that he is right in what he says — so much so that he is not willing to trust his listeners to make up their own minds from the evidence he presents, but insists instead on bending their will so they will uncritically accept his words.

Politicians do this all the time, at least the ones I would consider demagogues. With coaching from their handlers, they become skilled at "playing on emotion" to induce listeners to forego sound thinking and come together on the basis of feelings, alone.

It's how politics is generally done: exploiting the emotional weaknesses of human nature for polemical advantage. It's also why dishonest, fraudulent deceivers get elevated to high office.

Consider our current president, who made it to the White House largely by talking like a "rock star" who inspired his adoring "fans" to imagine (as the Lennon song by that name appeals through art, not logic) the transformation from God-centered values to man-made utopia, even inducing them to faint in the presence of the great Dreamer himself at campaign stops.

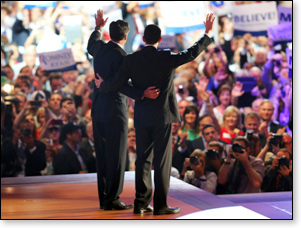

Consider, as well, the final night of the Republican National Convention in Tampa last week.

Masters of illusion

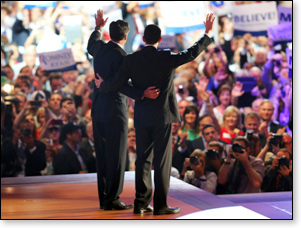

What viewers witnessed was an evening fraught with gimmickry deliberately calculated to elicit a desired audience response, a response not based in reason, or sound evidence, but contrived — and controlled — emotionalism. And if the effect on the respected PBS NewsHour panel covering the convention on the screen in my living room was any indication, the strategy worked.

All four seasoned journalists indicated in words or body language that they were deeply moved — against their better judgment — by the demagogic manipulation the Romney campaign served up to induce voters to see Mitt as a God-fearing, compassionate, principled, people-oriented human being, in contrast to the pretentious, insincere, uninspiring, pragmatic public persona observers generally see in Mitt.

One of the panelists was so impressed, he wondered out loud why such an effective strategy had not been used previously by the Romney camp.

We're not talking here about the humanizing of Mitt by his wife Ann two nights before. That speech was more straightforward, if understandably personal.

We're talking about an orchestrated attempt to pander to audience emotions, deliberately distorting reality.

(Mind you, we're not discounting the importance of emotion, per se — the kind that naturally results, on one level or another, from nearly all human interaction. Indeed, the best arguments, evidence, and facts are prone to engender an emotional response from listeners — either positive or negative. What we're objecting to here is the intentional use of emotion to persuade. That's pure demagoguery.)

Pastor Romney, I presume

Pastor Romney, I presume

The first overt demagogic appeal was made by a former counselor to Mitt when both served in a Mormon bishopric in Belmont, MA. The appeal was framed in deliberate misuse of the term "pastor" to describe Mitt's role, to foster sympathy for Mitt at the outset.

Unbeknownst to the uninitiated was the fact that in the Mormon church, there are no pastors in any customary sense. In most Christian denominations, a pastor is a spiritual guide who has significant authority and freedom to lead a congregation of believers in ways the self-sacrificing pastor deems both helpful and biblically orthodox. A pastor typically has considerable autonomy to lead his flock, and in more loosely-organized denominations, may have almost sole authority to define and pursue his role, using the scriptures — not institutional constraints — as the ultimate guide, and with believers free to adapt that guidance as they see fit.

Not so in Mormondom.

As a bishop, Mitt served as a lay member appointed by church authorities to lead his congregation within a highly institutional and controlled environment, one most non-Mormons can't even begin to envision. To fulfill his role, Mitt was expected to rely extensively on the control of higher lay leaders whose "counsel" was viewed as inspired of God. The Bible and other books of the LDS canon — in other words, the LDS scriptures — were viewed as secondary to such institutional focus.

At the center of this authoritarian structure was the church's Handbook of Instructions, which defined in substantial detail a bishop's (and member's) duties and requirements, giving little latitude for personal interpretation of that role, and little room for taking initiative outside prescribed protocol.

In reality, therefore, Mitt functioned more as a rank-and-file contact within an elaborate bureaucracy than as a genuine "pastor." Most pastors would recoil at calling such a diminished spiritual leader one of their own kind.

With that conscious exaggeration of Mitt's role as a "pastor," the former counselor to Mitt then proceeded to cite things Mitt did as one merely assigned to do so as a Mormon bureaucrat — as though he were a true pastor. The description of things Mitt did was clearly meant to play on the emotions of the audience. It portrayed Mitt as a caring shepherd who fed his flock from the goodness of his heart, always looking to supply their spiritual and material necessities with an eye to the commandments and teachings of God. In reality, the examples cited were right out of the handbook, reflecting standard duties all bishops in the church hierarchy were expected to fulfill.

As an obedient Mormon, Mitt simply did as he was told. The emotion-laden list of Mitt's activities implied he took it upon himself to lead fellow believers to greater reliance on God and his providence.

Pure pap. But it worked, in the sense that it set the tone for the emotionalism that was to follow.

Entirely absent from the counselor's portrait of Mitt as a compassionate spiritual leader was the illuminating fact that — during their time in the bishopric — they worked together at Bain & Company (which spawned Mitt's Bain Capital). Arguably, they were business associates whose like-mindedness paralleled their bureaucratic roles in the LDS church. Hence the man's selection to address the convention.

Bishop, I need help

Bishop, I need help

Two highly emotional accounts of Mitt's stewardship as a dutiful bishop in the Mormon hierarchy then followed. Both were couched in exaggerated terms that betrayed their intent to manipulate unsuspecting viewers and cause them to see Mitt as more of a Good Samaritan than he may in fact be.

A careful reading of the transcript reveals what discerning watchers could detect immediately: it was classic demagoguery, designed to convince through passion, not reliable fact.

First, an older couple spoke of their experiences with Mitt that began in the 1970's when he was apparently their home teacher (a church representative assigned to make monthly visits to several families); when he was later "in the vanguard of [the couple's] support system" in 1979 (in his role as either a home teacher or a counselor in the "stake presidency"), at which time the family learned their son was terminally ill; and when their son died while Mitt was their bishop in the early 80's.

The decade was condensed down to visits Mitt made to the 14-year-old boy's hospital room as he lay dying. The fact that the sequence was sketchy and hard to follow — focusing mainly on its emotional elements — suggested the central facts were less important than the desired emotional effect on the listener.

With all due respect to the older couple who lost their son, their presentation was patently manipulative, not duly considerate of the audience. It appeared authored by professionals in the Romney campaign for utmost sensational value, and came off as confusing and artificial.

The highlight of the story was the fact the boy asked Mitt — a lawyer — to help him draw up a will so he could "make sure his [prized possessions] were given to his closest friends and family." Most 14-year-olds, of course, would simply make a list for their parents to follow after their death, and not involve the legal system.

When the mother said, "That is a task no child should ever have to do" — in other words, have an attorney draft their will — the audience should have been alerted that something was out of kilter here.

The mother ended by saying, "We humbly wish that God will continue to bless Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan for their efforts. In doing so, He will bless the United States of America."

The presumption that God was pleased enough with Mitt to endorse his candidacy was not warranted by the vapid, highly-secular nature of Mitt's campaign to date — not just including the above prime-time idealization of his righteousness and compassion, but his verifiable institution of gay marriage in Massachusetts, his pro-choice legacy as governor (despite his rhetoric), and his modeling of the "individual mandate" in Romneycare that became the inspiration for Obamacare.

Indeed, God is no "progressive" socialist of the sort Mitt plainly is, and that alone argues that He would not support Mitt's bid for president.

The couple's presumptuous appeal for God to elect Mitt Romney was inappropriate and disturbing.

Who is my neighbor?

In the parable of the Good Samaritan, Jesus answers a question put to him by a clever lawyer — "Who is my neighbor?"

The Son of God tells the questioner of a Samaritan who stumbles upon a Jew who's been robbed, beaten, and left for dead, and — unlike two ecclesiastical officers who pass the man by — "had compassion on him," purely of his own initiative, unassigned to do so and unguided by a bureaucratic handbook.

At considerable sacrifice — again, without being expected to do so — the despised Samaritan took it upon himself to care for the man, and when he had to leave, then paid another man to follow up and bill him if needed.

Jesus asked, "Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbor unto him that fell among the thieves?

Jesus asked, "Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbor unto him that fell among the thieves?

"And he said, He that sheweth mercy on him. Then said Jesus unto him, Go and do thou likewise" (Luke 10:25-37).

This parable, and its precept, contrasts with the third sensational (though veiled) account of Mitt's service to God and man while in his bureaucratic calling.

The account was delivered by the wife of a venture capitalist whose family attended Mitt's congregation when Mitt was a bishop, while her husband was attending Harvard Law School in preparation for a career in private equity investment (Mitt's line of work).

The man had just graduated from Stanford University (where Mitt spent a year in the early 1970's), and he and his family moved to the Boston area in 1982.

The husband and Mitt thus had much in common, and their families became close friends.

The wife began her remarks by saying that not long after she and her family moved to Boston, they were visited by the bishop of their new "ward" (an assigned congregation) — Mitt Romney — and she was embarrassed they didn't have a dryer, a lack not uncommon for people who've recently moved in. The way this fact is described by the woman gives the audience the impression the family was poor and struggling. That would undoubtedly be a false impression, in view of her husband's esteemed opportunity at Harvard.

But it plays nicely upon the emotions at a political convention.

The speaker then notes throughout her talk that she and the Romneys had a "treasure of friendship" and took care of each others' children — treating them like their own — something only the most familiar and trusting of friends would do.

It was in this context that she mentions Mitt's efforts "as our clergy" to comfort her following the premature birth of a daughter, and the Romneys' willingness to help care for their friends' two-year-old son, Peter.

She added details about a Thanksgiving feast the Romneys made for the family in their time of need, and the graciousness with which the Romneys extended sympathy and love to their long-time friends when — 26 years later — the struggling girl passed away.

With that description of the Romneys' close friendship and support, the woman then generalizes and says, "It seems to me when it comes to loving our neighbor, we can talk about it, or we can live it. The Romneys live it every single day."

An exaggeration? I think so, especially when you take into account the backdrop for the Romneys' expressions of kindness and compassion toward this particular family: their strong, enduring friendship, based in their common pursuits.

In actuality, the very idea of being a Good Samaritan — and thus a good "neighbor" — is to love, serve, and sacrifice for those we don't even know who happen to need our help, as God puts them in our path, and as we live our day-to-day lives no matter our ecclesiastical affiliation or position.

The woman ends by saying that Mitt "has devoted his entire life [to] quietly serving others."

This claim unfortunately contradicts Mitt's known actions in the political arena that have led to the deaths of countless unborn babies; his initiation — without a legal requirement to do so — of same-sex marriage in Massachusetts, thus threatening the continued existence of the God-ordained family in the U.S.; and his lobbying for the Obama administration to pattern its healthcare plan after Mitt's own un-American Romneycare.

This claim unfortunately contradicts Mitt's known actions in the political arena that have led to the deaths of countless unborn babies; his initiation — without a legal requirement to do so — of same-sex marriage in Massachusetts, thus threatening the continued existence of the God-ordained family in the U.S.; and his lobbying for the Obama administration to pattern its healthcare plan after Mitt's own un-American Romneycare.

"A man convinced against his will..."

We're not suggesting here that the basic facts at the core of the three emotional appeals cited from last week's GOP convention may not be truthful. Our main concern is that they were obviously exaggerated.

More importantly, we're concerned about why the facts were exaggerated: obviously, to persuade through contrived, deliberate use of emotion.

That's not what ultimately persuades.

Years ago, when I was on my Mormon mission, an assigned companion was fond of reciting, "A man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still."

As time passes, the emotionalism of the above accounts will diminish, and hearers will reflect on some of the things that appeared contradictory or shallow or manipulative to them. The result is likely to be less respect — among those prone to think for themselves — for Mr. Romney, not more.

September 3, 2012

One valid definition of "demagoguery" is the intentional use of emotion to sway people's thinking.

One valid definition of "demagoguery" is the intentional use of emotion to sway people's thinking.Suppose a speaker wants to convince an unsympathetic audience that he is right in what he says — so much so that he is not willing to trust his listeners to make up their own minds from the evidence he presents, but insists instead on bending their will so they will uncritically accept his words.

Politicians do this all the time, at least the ones I would consider demagogues. With coaching from their handlers, they become skilled at "playing on emotion" to induce listeners to forego sound thinking and come together on the basis of feelings, alone.

It's how politics is generally done: exploiting the emotional weaknesses of human nature for polemical advantage. It's also why dishonest, fraudulent deceivers get elevated to high office.

Consider our current president, who made it to the White House largely by talking like a "rock star" who inspired his adoring "fans" to imagine (as the Lennon song by that name appeals through art, not logic) the transformation from God-centered values to man-made utopia, even inducing them to faint in the presence of the great Dreamer himself at campaign stops.

Consider, as well, the final night of the Republican National Convention in Tampa last week.

Masters of illusion

What viewers witnessed was an evening fraught with gimmickry deliberately calculated to elicit a desired audience response, a response not based in reason, or sound evidence, but contrived — and controlled — emotionalism. And if the effect on the respected PBS NewsHour panel covering the convention on the screen in my living room was any indication, the strategy worked.

All four seasoned journalists indicated in words or body language that they were deeply moved — against their better judgment — by the demagogic manipulation the Romney campaign served up to induce voters to see Mitt as a God-fearing, compassionate, principled, people-oriented human being, in contrast to the pretentious, insincere, uninspiring, pragmatic public persona observers generally see in Mitt.

One of the panelists was so impressed, he wondered out loud why such an effective strategy had not been used previously by the Romney camp.

We're not talking here about the humanizing of Mitt by his wife Ann two nights before. That speech was more straightforward, if understandably personal.

We're talking about an orchestrated attempt to pander to audience emotions, deliberately distorting reality.

(Mind you, we're not discounting the importance of emotion, per se — the kind that naturally results, on one level or another, from nearly all human interaction. Indeed, the best arguments, evidence, and facts are prone to engender an emotional response from listeners — either positive or negative. What we're objecting to here is the intentional use of emotion to persuade. That's pure demagoguery.)

Pastor Romney, I presume

Pastor Romney, I presumeThe first overt demagogic appeal was made by a former counselor to Mitt when both served in a Mormon bishopric in Belmont, MA. The appeal was framed in deliberate misuse of the term "pastor" to describe Mitt's role, to foster sympathy for Mitt at the outset.

Unbeknownst to the uninitiated was the fact that in the Mormon church, there are no pastors in any customary sense. In most Christian denominations, a pastor is a spiritual guide who has significant authority and freedom to lead a congregation of believers in ways the self-sacrificing pastor deems both helpful and biblically orthodox. A pastor typically has considerable autonomy to lead his flock, and in more loosely-organized denominations, may have almost sole authority to define and pursue his role, using the scriptures — not institutional constraints — as the ultimate guide, and with believers free to adapt that guidance as they see fit.

Not so in Mormondom.

As a bishop, Mitt served as a lay member appointed by church authorities to lead his congregation within a highly institutional and controlled environment, one most non-Mormons can't even begin to envision. To fulfill his role, Mitt was expected to rely extensively on the control of higher lay leaders whose "counsel" was viewed as inspired of God. The Bible and other books of the LDS canon — in other words, the LDS scriptures — were viewed as secondary to such institutional focus.

At the center of this authoritarian structure was the church's Handbook of Instructions, which defined in substantial detail a bishop's (and member's) duties and requirements, giving little latitude for personal interpretation of that role, and little room for taking initiative outside prescribed protocol.

In reality, therefore, Mitt functioned more as a rank-and-file contact within an elaborate bureaucracy than as a genuine "pastor." Most pastors would recoil at calling such a diminished spiritual leader one of their own kind.

With that conscious exaggeration of Mitt's role as a "pastor," the former counselor to Mitt then proceeded to cite things Mitt did as one merely assigned to do so as a Mormon bureaucrat — as though he were a true pastor. The description of things Mitt did was clearly meant to play on the emotions of the audience. It portrayed Mitt as a caring shepherd who fed his flock from the goodness of his heart, always looking to supply their spiritual and material necessities with an eye to the commandments and teachings of God. In reality, the examples cited were right out of the handbook, reflecting standard duties all bishops in the church hierarchy were expected to fulfill.

As an obedient Mormon, Mitt simply did as he was told. The emotion-laden list of Mitt's activities implied he took it upon himself to lead fellow believers to greater reliance on God and his providence.

Pure pap. But it worked, in the sense that it set the tone for the emotionalism that was to follow.

Entirely absent from the counselor's portrait of Mitt as a compassionate spiritual leader was the illuminating fact that — during their time in the bishopric — they worked together at Bain & Company (which spawned Mitt's Bain Capital). Arguably, they were business associates whose like-mindedness paralleled their bureaucratic roles in the LDS church. Hence the man's selection to address the convention.

Bishop, I need help

Bishop, I need helpTwo highly emotional accounts of Mitt's stewardship as a dutiful bishop in the Mormon hierarchy then followed. Both were couched in exaggerated terms that betrayed their intent to manipulate unsuspecting viewers and cause them to see Mitt as more of a Good Samaritan than he may in fact be.

A careful reading of the transcript reveals what discerning watchers could detect immediately: it was classic demagoguery, designed to convince through passion, not reliable fact.

First, an older couple spoke of their experiences with Mitt that began in the 1970's when he was apparently their home teacher (a church representative assigned to make monthly visits to several families); when he was later "in the vanguard of [the couple's] support system" in 1979 (in his role as either a home teacher or a counselor in the "stake presidency"), at which time the family learned their son was terminally ill; and when their son died while Mitt was their bishop in the early 80's.

The decade was condensed down to visits Mitt made to the 14-year-old boy's hospital room as he lay dying. The fact that the sequence was sketchy and hard to follow — focusing mainly on its emotional elements — suggested the central facts were less important than the desired emotional effect on the listener.

With all due respect to the older couple who lost their son, their presentation was patently manipulative, not duly considerate of the audience. It appeared authored by professionals in the Romney campaign for utmost sensational value, and came off as confusing and artificial.

The highlight of the story was the fact the boy asked Mitt — a lawyer — to help him draw up a will so he could "make sure his [prized possessions] were given to his closest friends and family." Most 14-year-olds, of course, would simply make a list for their parents to follow after their death, and not involve the legal system.

When the mother said, "That is a task no child should ever have to do" — in other words, have an attorney draft their will — the audience should have been alerted that something was out of kilter here.

The mother ended by saying, "We humbly wish that God will continue to bless Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan for their efforts. In doing so, He will bless the United States of America."

The presumption that God was pleased enough with Mitt to endorse his candidacy was not warranted by the vapid, highly-secular nature of Mitt's campaign to date — not just including the above prime-time idealization of his righteousness and compassion, but his verifiable institution of gay marriage in Massachusetts, his pro-choice legacy as governor (despite his rhetoric), and his modeling of the "individual mandate" in Romneycare that became the inspiration for Obamacare.

Indeed, God is no "progressive" socialist of the sort Mitt plainly is, and that alone argues that He would not support Mitt's bid for president.

The couple's presumptuous appeal for God to elect Mitt Romney was inappropriate and disturbing.

Who is my neighbor?

In the parable of the Good Samaritan, Jesus answers a question put to him by a clever lawyer — "Who is my neighbor?"

The Son of God tells the questioner of a Samaritan who stumbles upon a Jew who's been robbed, beaten, and left for dead, and — unlike two ecclesiastical officers who pass the man by — "had compassion on him," purely of his own initiative, unassigned to do so and unguided by a bureaucratic handbook.

At considerable sacrifice — again, without being expected to do so — the despised Samaritan took it upon himself to care for the man, and when he had to leave, then paid another man to follow up and bill him if needed.

Jesus asked, "Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbor unto him that fell among the thieves?

Jesus asked, "Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbor unto him that fell among the thieves?"And he said, He that sheweth mercy on him. Then said Jesus unto him, Go and do thou likewise" (Luke 10:25-37).

This parable, and its precept, contrasts with the third sensational (though veiled) account of Mitt's service to God and man while in his bureaucratic calling.

The account was delivered by the wife of a venture capitalist whose family attended Mitt's congregation when Mitt was a bishop, while her husband was attending Harvard Law School in preparation for a career in private equity investment (Mitt's line of work).

The man had just graduated from Stanford University (where Mitt spent a year in the early 1970's), and he and his family moved to the Boston area in 1982.

The husband and Mitt thus had much in common, and their families became close friends.

The wife began her remarks by saying that not long after she and her family moved to Boston, they were visited by the bishop of their new "ward" (an assigned congregation) — Mitt Romney — and she was embarrassed they didn't have a dryer, a lack not uncommon for people who've recently moved in. The way this fact is described by the woman gives the audience the impression the family was poor and struggling. That would undoubtedly be a false impression, in view of her husband's esteemed opportunity at Harvard.

But it plays nicely upon the emotions at a political convention.

The speaker then notes throughout her talk that she and the Romneys had a "treasure of friendship" and took care of each others' children — treating them like their own — something only the most familiar and trusting of friends would do.

It was in this context that she mentions Mitt's efforts "as our clergy" to comfort her following the premature birth of a daughter, and the Romneys' willingness to help care for their friends' two-year-old son, Peter.

She added details about a Thanksgiving feast the Romneys made for the family in their time of need, and the graciousness with which the Romneys extended sympathy and love to their long-time friends when — 26 years later — the struggling girl passed away.

With that description of the Romneys' close friendship and support, the woman then generalizes and says, "It seems to me when it comes to loving our neighbor, we can talk about it, or we can live it. The Romneys live it every single day."

An exaggeration? I think so, especially when you take into account the backdrop for the Romneys' expressions of kindness and compassion toward this particular family: their strong, enduring friendship, based in their common pursuits.

In actuality, the very idea of being a Good Samaritan — and thus a good "neighbor" — is to love, serve, and sacrifice for those we don't even know who happen to need our help, as God puts them in our path, and as we live our day-to-day lives no matter our ecclesiastical affiliation or position.

The woman ends by saying that Mitt "has devoted his entire life [to] quietly serving others."

This claim unfortunately contradicts Mitt's known actions in the political arena that have led to the deaths of countless unborn babies; his initiation — without a legal requirement to do so — of same-sex marriage in Massachusetts, thus threatening the continued existence of the God-ordained family in the U.S.; and his lobbying for the Obama administration to pattern its healthcare plan after Mitt's own un-American Romneycare.

This claim unfortunately contradicts Mitt's known actions in the political arena that have led to the deaths of countless unborn babies; his initiation — without a legal requirement to do so — of same-sex marriage in Massachusetts, thus threatening the continued existence of the God-ordained family in the U.S.; and his lobbying for the Obama administration to pattern its healthcare plan after Mitt's own un-American Romneycare."A man convinced against his will..."

We're not suggesting here that the basic facts at the core of the three emotional appeals cited from last week's GOP convention may not be truthful. Our main concern is that they were obviously exaggerated.

More importantly, we're concerned about why the facts were exaggerated: obviously, to persuade through contrived, deliberate use of emotion.

That's not what ultimately persuades.

Years ago, when I was on my Mormon mission, an assigned companion was fond of reciting, "A man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still."

As time passes, the emotionalism of the above accounts will diminish, and hearers will reflect on some of the things that appeared contradictory or shallow or manipulative to them. The result is likely to be less respect — among those prone to think for themselves — for Mr. Romney, not more.