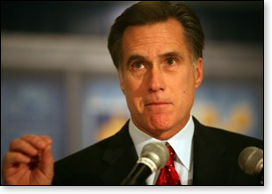

Inside Mitt's mind

Stephen Stone, RenewAmerica President

Mitt Romney and I went on our Mormon missions exactly the same time. Born in March 1947, we spent a week together — along with 200 other new LDS missionaries — being trained in a converted hotel in downtown Salt Lake City that is now the site of the church's 21,000-seat Conference Center.

Mitt Romney and I went on our Mormon missions exactly the same time. Born in March 1947, we spent a week together — along with 200 other new LDS missionaries — being trained in a converted hotel in downtown Salt Lake City that is now the site of the church's 21,000-seat Conference Center.

Of course, Mitt wouldn't remember me (we never talked), but he sat right in front of me during most of the training sessions. At the end of the week, I entertained Mitt and the rest of the missionaries with my guitar, as I sang Peter, Paul, and Mary's version of "Early Morning Rain" — but with the lyrics altered, since it was about fast women and being "cold and drunk" on the outskirts of an airport (things I literally knew nothing about). It's one of my favorite songs, which I still sing regularly — altered lyrics and all.

I thought it ironic, at the time, that I would be in the "mission home" the same week as Mitt, since I knew I was going to Michigan — where his dad, George W. Romney, a popular icon in Mormondom, was governor. As it turned out, I served in Detroit and Lansing, along with several other cities in the region.

By another coincidence, at the time I was courting my wife DeeAnn, when we were both seniors at Brigham Young University, I lived a few houses up the street from Mitt's basement apartment, where he and Ann were living as newlyweds. I passed the building every day on my way to teach guitar at Herger Music in downtown Provo (humming, no doubt, my favorite song).

By a third coincidence, Mitt and I both graduated in English in 1971 from BYU, where he gave the valedictory address (while I was attending graduate school elsewhere, and was glad to be away from the authoritarian center of LDS culture).

Where's Mitt?

A little more background...

Since my dad (who twice almost became president of BYU) idealized Mitt's dad (a well-known automobile industrialist) — and because my life had the above incidental overlaps with Mitt's — I've always taken an interest in Mitt's life and career. I know details about him most other LDS-raised Americans wouldn't.

I've always known, for instance, that Mitt held the highest position a missionary could attain during his mission to France, an "assistant to the president" — an esteemed office gained only by the most obedient of missionaries within the framework of the highly-controlling mission regimen.

I was also aware that, while he was in France, Mitt was driving a mission vehicle that was hit head-on by another car, killing the mission president's wife, an experience that had to be life-altering for Mitt, who was seriously injured.

I knew that Mitt's oldest son was named Taggart. I thought that fact memorable since one of the most popular missionaries in my mission before I arrived was an Elder Taggart. I can only assume Elder Taggart was well known to the Romney family in the Bloomfield Hills area of the mission, and that Mitt possibly chose to name his first child after him — although I'm just guessing. Elder Taggart went on to become a prominent campus figure at BYU when Mitt and I were both there after our missions, further fueling my presumption.

I knew that Mitt's mother, Lenore — who ran for the U.S. Senate in 1970 — was explicitly pro-choice in her public life, something at odds with Mormon teachings.

I knew that Mitt ran against Ted Kennedy in the early 1990's on the same liberal pro-choice stance his mother instilled in him — a fact that made me wonder why he wasn't excommunicated from the LDS church for serious public apostasy.

I knew that Mitt nearly ran for governor of Utah, instead of Massachusetts, when he was considering how best to parlay his newly-elevated public persona in the aftermath the Salt Lake Olympic Games into another bid for high office.

I know that Mitt has always been viewed in Mormon circles (which are infused with deeply-rooted pragmatism) as the church's best hope of taking Mormonism "out of obscurity" and into the national spotlight, in fulfillment of predictions in Mormon culture that the church would ultimately "fill the whole earth." When his father, George, made his ill-fated attempt to carry that banner for the church, he was viewed by Mormons with much the same reverence. Having obtained Ivy League business and legal credentials, as well as unimaginable wealth, Mitt the son has now assumed an even more prophetic mantle of destiny than his dad.

I also know — as only a few others might recall — that one of the most surprising actions by Mitt when he oversaw the Salt Lake Olympics was an incident reported by a local TV station, in which Mitt angrily swore at automobile drivers who were being uncooperative on a snowy route leading to one of the major venues. I was a bit taken back when I saw the news. It wasn't the carefully-cultivated image most Mormons hold of Mitt.

I cite these memories to underscore at the outset of this look into Mitt's mind that I have more than a superficial — or PR-groomed — perception of Mitt.

Washing of the brain

Washing of the brain

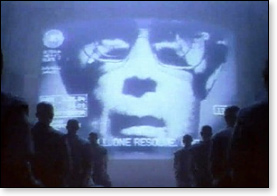

Having, myself, served an LDS mission — an indescribably-controlling experience that can accurately be characterized as institutional brainwashing designed to ensure successive generations of "prepared" and "believing" Mormon leaders — I can attest that the way Mitt thinks can largely be attributed to the 2½ years of daily mental and behavioral regimentation he experienced on his mission.

For Mitt, this intensive training in Mormon cultural values and beliefs began in July 1966 and ended in December 1968, at a time when the world itself was in cultural upheaval, heightening the intensity of the "mission experience" for any participant during that era.

(Note that non-English-speaking missions in Mitt's day were for 2½ years, making them even more impressive upon the minds of young men and women than English-speaking missions like mine, which was for two years.)

Let me explain why I equate the Mormon mission experience with "brainwashing."

Brainwashing — which depends, of course, on the receptiveness of the recipient for its effectiveness — typically involves two things:

Bear in mind that in normal life, we naturally pace our own mental and physical efforts in a way that allows us to self-monitor both factors to our personal benefit. If we're too exhausted from physical activity, let's say, we tend to back off in forming firm conclusions or commitments, being "too tired to think." If we find ourselves overwhelmed from mental activity, on the other hand, we often take time off and do something physically exertive (of our own choosing), and afterward relax, to keep our mental processes "in perspective" and in reasonable "balance."

Ungodly behaviorism

Not so with brainwashing! In that case, someone other than ourselves is in charge of defining our daily life in a manner that imposes both inordinate physical and mental stress constantly upon us, with the result that the weak-minded among us often fall prey to being "brainwashed" — accepting the intended lifestyle and the value framework that goes with it.

Such external control leaves us little opportunity to "think things through," and we end up making artificial, unwise, inaccurate judgments. For some of us, those results can be enduring, even for life, depending on the intensity of the externally-imposed training, and our degree of submissiveness.

I might point out that we all experience such external attempts to control our thinking and behavior in formal schooling and other institutional settings. Mormons don't have a patent on such overt mind control and behaviorism — they just do it with exceptional thoroughness and success.

Interestingly enough, Mitt's industrialist father (who felt his mission was instrumental in molding him) lost his chance to become president over a comment he made to the press that he was "brainwashed" by American military leaders when he visited the Vietnam War zone in the tumultuous 1960's. He was perceived as not tough enough to be president.

It's worth noting that when Mitt went on his mission, he himself was like "thin tissue" (he says) in his appreciation of his Mormon faith. He was thus easily influenced by the carefully-controlled mental and physical regimen of his mission.

I found the LDS mission regimen ungodly, myself, in a way that (among other things) contravened longstanding LDS belief in what is called "free agency" (the same thing as the philosophical term "free will"). Mormon culture outside the "mission field" generally prizes freedom of thought and action, in accord with scriptural guidelines. In the mission field, however — that "theater of operations" outside well-established Mormon culture — such personal freedom, vital to true learning and growth, can be smothered under a code of imposed rules, dictated choices, and required dependency on the mission "parents" (the president and his wife), as well as on young missionaries placed over slightly younger ones to lead, guide, tutor, and yes, control them.

The result, at the time I went, was a two (or two-and-a-half) year virtual hell for those with any reasonable sense of their God-given "agency" and their doctrine-based accountability to God. The mission was designed to be a "spiritual boot-camp" for weeding out compliant future leaders from chaff who refused to go along.

The result, at the time I went, was a two (or two-and-a-half) year virtual hell for those with any reasonable sense of their God-given "agency" and their doctrine-based accountability to God. The mission was designed to be a "spiritual boot-camp" for weeding out compliant future leaders from chaff who refused to go along.

Mitt went along, with great skill and apparent enthusiasm.

Junior executives

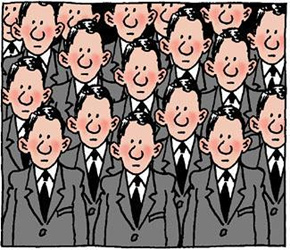

As Mormon missionaries today continue to walk the world's streets looking like junior executives (in my day, we were mistaken for CIA agents), let me point out that during my mission, I was shocked at the obvious conflict between what I'd learned growing up in the LDS church in Utah and California, and what I was being told was true, orthodox, and expected on my mission in the Great Lakes region of America. They were not one and the same at all — to my mind.

The first allowed broad personal interpretation and application of LDS doctrine as I sought my own understanding and priorities, using the LDS canon as my guide (and my prior commitment and understanding regarding Christ's saving doctrine). The second was a "practical," "business-minded" sales model for converting not just the world to Mormonism, but the missionary himself.

The mission approach at the time was thoroughly based in methods and techniques that emphasized setting measurable goals, achieving measurable results, competing with other missionaries for recognition, and twisting the arm of God to go along (a perversion of true faith).

It's very much the way the whole church operates today at every level (I've learned from my 60-plus years of observing the church from the inside) — but without the invasive 24/7 control typical of the mission field. Local church leaders have less direct influence over each individual (although they often indicate they wish they had more). Even so, the day-to-day relationship of regular members and their local "bureaucratic" leaders is arguably more authoritarian and controlling than that found in any other institution or culture in existence that professes to be Christian.

The reason: the church's corporate "business" model, combined with a claimed automatic right of leaders to divine revelation. Local leaders — as well as a large proportion of the membership — learned this approach on their missions and are simply being true to their training.

I should add that such an authoritarian business management approach, as exists from top to bottom in the church, is alien to scripture and contrary to the principles of salvation for which Christ died. It trivializes — and prostitutes — the very gospel of Christ itself.

I learned this reality — this disparity between reasonable, personal religion and overbearing institutional control — after just a few weeks into my mission in the suburbs of Detroit. I've seen it confirmed repeatedly and unmistakably in the many years since. The church's decidedly "corporate management" model may seem an impressive strength from a worldly institutional perspective, but it's an ecclesiastical disaster, leading all who adopt it, or cater to it, further from Christ and His salvation, not closer.

Positive thinking

In this pragmatic, results-oriented ecclesiastical framework — a framework, as stressed, outside the doctrinal canon of the church — we now take up Mitt's own embrace 45 years ago of what was then called in the mission field "Positive Mental Attitude."

It's a value system that has guided Mitt ever since (and can still be found extensively throughout Mormon culture).

A Positive Mental Attitude was the paramount, defining value in my own mission, as it was in Mitt's. The difference for the two of us is that I rejected it as a perversion of authentic faith in Christ, while Mitt adopted it wholeheartedly, becoming deeply "converted" to it.

What is "PMA," as some call it?

Most of us are familiar with "positive thinking" in one form or another. In its innocuous forms, it's basically the idea of an upbeat, positive outlook, the kind that is helpful in dealing with life's ups and downs.

No one would disparage that kind of cheerful, positive optimism.

But the philosophy of positive thinking is more explicit and far-reaching than that and says in essence, no matter its variations:

"Whatever the mind of man can conceive and believe, it can achieve."

In the late 1930's, at the height of the depression, this philosophy became popular as the centerpiece of Napoleon Hill's best-selling Think and Grow Rich.

This book — with its philosophical groundings in the above article of faith — has served for decades as the conceptual "bible" of the business world, particularly of those who sincerely wish to "grow rich" through dedicated application of the "principle of positive thinking."

Here's the problem:

Here's the problem:

The central premise of Think and Grow Rich — belief in auto-suggestive, self-assertive "positive thinking" — is a godless absurdity, and those who accept it as true are self-deluded.

The notion that "whatever" a person can think of and believe strongly enough will come to fruition is not an article of faith at all. It's an article of faithlessness.

It's not a tenet of godly behavior, as some presume, but the very essence of godless behavior. It's the premise of atheism — which literally means "without God."

It suggests we don't need God, that we can "bargain with life on [our] own terms" (to quote from Hill's preface) — accomplishing by ourselves anything we choose.

It verbalizes what those without God want to believe — not what is eternally or intrinsically true.

It's as evil an idea as ever there could be, and it deprives its adherent of God's salvation — which is contingent on submission to His will in all we do, with our whole souls.

Jesus said, "without me ye can do nothing" (John 15:5).

The truth is, nothing we can "conceive and believe" can be done in a way that will please God. We might succeed in doing what we want for a time — to our detriment (for "whatsoever is not of faith is sin"); but we will lose any hope of salvation if we attempt to live consistently in such a godless manner.

Only as we seek to avoid such self-centered, prideful behavior — and instead submit ourselves fully to God, doing His will, His way — can we gain eternal life as promised by scripture (see John 5:19-20,30; 8:28-29; and 14:6).

Nothing in the Bible is more plain.

Go and sell all that thou hast...

So how did Mitt get caught up in such an inherently atheistic way of believing?

From his mission.

Specifically, from a high church leader who recommended the book Think and Grow Rich to the missionaries in Mitt's mission. This same leader — later to become "president of the church" — was not alone in such advocacy. The book — and its philosophy — was rampant throughout the church's missions, since numerous governing "general authorities" believed its pragmatism would help boost the rate of "convert baptisms."

I recall encountering the book and its "positive thinking" frequently among the missionaries and leaders in my own mission. I also recall informing these perverters of faith in God that they were seriously misguided.

Positive thinking — or Positive Mental Attitude — was not true faith, I told them. It was its antithesis.

Thankfully, in today's LDS governing leadership, some express much the same sentiment as I tried to communicate. But back in the 1960's, few, if any, did. Think and Grow Rich was held in highest esteem in the church, and "positive thinking" was so popular in the church, I encountered it casually when I was home from my first year of college and a speaker gave a well-attended seminar on it at our local "stake center." This was a year before my mission.

Imagine God looking down upon such profane evil in an "ecclesiastical" setting.

Back to Mitt. According to a missionary companion, Mitt complied with the above church leader's counsel and took the book to heart as a guide for success with anything and everything — even telling a missionary conference, Mitt wrote in his journal, "we can obtain anything we want in life — if we want it badly enough," a summation of Hill's book.

Mitt traveled the mission preaching that message to other missionaries to help them "reach their goals."

At one point, Mitt (with two associates) created a pamphlet based on Hill's teachings and gave it to the mission's 200 other missionaries when Mitt and another "assistant to the president" ran the mission in the absence of the mission president — who had returned home for two months. During that time, Mitt "cracked the whip," an associate commented, and led the mission to more than doubling its baptism rate, "proving" to himself and others the value of positive thinking.

The idea of mimicking business principles in "selling" the LDS church's message clearly appealed to Mitt, and in turn helped form his most basic values.

Interestingly, at BYU shortly after his mission, Mitt organized a telethon using the sales techniques he gleaned from Think and Grow Rich, raising a million dollars for the university in the process and setting a pattern for his life's work.

Observations

I have a whole file of references, quotes, testimonials, and other information to support the above hypothesis: that Mitt is a deeply-committed positive thinker who sincerely believes such a godless "business" approach is the practical foundation for all meaningful success — particularly for Mormons who paradoxically believe they are on God's errand in making the world better.

Nothing could be more mistaken, of course, as a philosophy for public or personal good.

But this hypothesis explains Mitt's thoroughgoing pragmatism; his meandering relativism; his superficial view of God and His teachings; his fabled lack of a discernible "moral core"; his bureaucratic, corporate-minded tendencies; his preoccupation with what can be measured and counted; his lifelong obsession with thinking big about himself and his abilities; and his unprincipled inclination to compromise.

But this hypothesis explains Mitt's thoroughgoing pragmatism; his meandering relativism; his superficial view of God and His teachings; his fabled lack of a discernible "moral core"; his bureaucratic, corporate-minded tendencies; his preoccupation with what can be measured and counted; his lifelong obsession with thinking big about himself and his abilities; and his unprincipled inclination to compromise.

He's just doing what Mr. Hill made sound true and attractive in his influential guide to selling oneself and one's ideas, a philosophy Mitt learned in the controlling crucible of his LDS mission.

Never mind that Mitt's own church contradicts such thinking and behavior in its canon, in a strongly worded condemnation of preoccupation with worldly success and the notion of "selling oneself" — in words that seem tailored to Mitt himself:

I raise these issues and facts not to disparage Mitt, nor even to dissuade those who are determined to vote for him on purely pragmatic grounds — but to educate interested Americans in the connection between Mitt and his mission, which went a long way toward "making the man." It's a connection that's vital to getting inside Mitt's mind.

In the meantime, I can't get out of my own mind an image of the quintessential positive thinker, Stuart Smalley, portrayed by now-Senator Al Franken years ago on Saturday Night Live, who would end each satirical segment by saying — with self-affirming sincerity into a mirror: "I'm good enough, I'm smart enough, and doggone it, people like me."

Such is the image-conscious world of self-deception conjured by all who seriously subscribe to positive thinking.

© Stephen Stone

October 22, 2012

Mitt Romney and I went on our Mormon missions exactly the same time. Born in March 1947, we spent a week together — along with 200 other new LDS missionaries — being trained in a converted hotel in downtown Salt Lake City that is now the site of the church's 21,000-seat Conference Center.

Mitt Romney and I went on our Mormon missions exactly the same time. Born in March 1947, we spent a week together — along with 200 other new LDS missionaries — being trained in a converted hotel in downtown Salt Lake City that is now the site of the church's 21,000-seat Conference Center.Of course, Mitt wouldn't remember me (we never talked), but he sat right in front of me during most of the training sessions. At the end of the week, I entertained Mitt and the rest of the missionaries with my guitar, as I sang Peter, Paul, and Mary's version of "Early Morning Rain" — but with the lyrics altered, since it was about fast women and being "cold and drunk" on the outskirts of an airport (things I literally knew nothing about). It's one of my favorite songs, which I still sing regularly — altered lyrics and all.

I thought it ironic, at the time, that I would be in the "mission home" the same week as Mitt, since I knew I was going to Michigan — where his dad, George W. Romney, a popular icon in Mormondom, was governor. As it turned out, I served in Detroit and Lansing, along with several other cities in the region.

By another coincidence, at the time I was courting my wife DeeAnn, when we were both seniors at Brigham Young University, I lived a few houses up the street from Mitt's basement apartment, where he and Ann were living as newlyweds. I passed the building every day on my way to teach guitar at Herger Music in downtown Provo (humming, no doubt, my favorite song).

By a third coincidence, Mitt and I both graduated in English in 1971 from BYU, where he gave the valedictory address (while I was attending graduate school elsewhere, and was glad to be away from the authoritarian center of LDS culture).

Where's Mitt?

A little more background...

Since my dad (who twice almost became president of BYU) idealized Mitt's dad (a well-known automobile industrialist) — and because my life had the above incidental overlaps with Mitt's — I've always taken an interest in Mitt's life and career. I know details about him most other LDS-raised Americans wouldn't.

I've always known, for instance, that Mitt held the highest position a missionary could attain during his mission to France, an "assistant to the president" — an esteemed office gained only by the most obedient of missionaries within the framework of the highly-controlling mission regimen.

I was also aware that, while he was in France, Mitt was driving a mission vehicle that was hit head-on by another car, killing the mission president's wife, an experience that had to be life-altering for Mitt, who was seriously injured.

I knew that Mitt's oldest son was named Taggart. I thought that fact memorable since one of the most popular missionaries in my mission before I arrived was an Elder Taggart. I can only assume Elder Taggart was well known to the Romney family in the Bloomfield Hills area of the mission, and that Mitt possibly chose to name his first child after him — although I'm just guessing. Elder Taggart went on to become a prominent campus figure at BYU when Mitt and I were both there after our missions, further fueling my presumption.

I knew that Mitt's mother, Lenore — who ran for the U.S. Senate in 1970 — was explicitly pro-choice in her public life, something at odds with Mormon teachings.

I knew that Mitt ran against Ted Kennedy in the early 1990's on the same liberal pro-choice stance his mother instilled in him — a fact that made me wonder why he wasn't excommunicated from the LDS church for serious public apostasy.

I knew that Mitt nearly ran for governor of Utah, instead of Massachusetts, when he was considering how best to parlay his newly-elevated public persona in the aftermath the Salt Lake Olympic Games into another bid for high office.

I know that Mitt has always been viewed in Mormon circles (which are infused with deeply-rooted pragmatism) as the church's best hope of taking Mormonism "out of obscurity" and into the national spotlight, in fulfillment of predictions in Mormon culture that the church would ultimately "fill the whole earth." When his father, George, made his ill-fated attempt to carry that banner for the church, he was viewed by Mormons with much the same reverence. Having obtained Ivy League business and legal credentials, as well as unimaginable wealth, Mitt the son has now assumed an even more prophetic mantle of destiny than his dad.

I also know — as only a few others might recall — that one of the most surprising actions by Mitt when he oversaw the Salt Lake Olympics was an incident reported by a local TV station, in which Mitt angrily swore at automobile drivers who were being uncooperative on a snowy route leading to one of the major venues. I was a bit taken back when I saw the news. It wasn't the carefully-cultivated image most Mormons hold of Mitt.

I cite these memories to underscore at the outset of this look into Mitt's mind that I have more than a superficial — or PR-groomed — perception of Mitt.

Washing of the brain

Washing of the brainHaving, myself, served an LDS mission — an indescribably-controlling experience that can accurately be characterized as institutional brainwashing designed to ensure successive generations of "prepared" and "believing" Mormon leaders — I can attest that the way Mitt thinks can largely be attributed to the 2½ years of daily mental and behavioral regimentation he experienced on his mission.

For Mitt, this intensive training in Mormon cultural values and beliefs began in July 1966 and ended in December 1968, at a time when the world itself was in cultural upheaval, heightening the intensity of the "mission experience" for any participant during that era.

(Note that non-English-speaking missions in Mitt's day were for 2½ years, making them even more impressive upon the minds of young men and women than English-speaking missions like mine, which was for two years.)

Let me explain why I equate the Mormon mission experience with "brainwashing."

Brainwashing — which depends, of course, on the receptiveness of the recipient for its effectiveness — typically involves two things:

- Keeping a person so exhausted from long hours of strenuous work or pressure day after day that they have little time to reflect, evaluate, assimilate, compare, or otherwise exercise normal thought regarding what they are exhaustively engaged in, or why.

- Immersing that same person at the same time in incessant indoctrination of challenging ideas they have little prior understanding of, or inherent desire to learn (hence the reason for their lack of prior understanding).

Bear in mind that in normal life, we naturally pace our own mental and physical efforts in a way that allows us to self-monitor both factors to our personal benefit. If we're too exhausted from physical activity, let's say, we tend to back off in forming firm conclusions or commitments, being "too tired to think." If we find ourselves overwhelmed from mental activity, on the other hand, we often take time off and do something physically exertive (of our own choosing), and afterward relax, to keep our mental processes "in perspective" and in reasonable "balance."

Ungodly behaviorism

Not so with brainwashing! In that case, someone other than ourselves is in charge of defining our daily life in a manner that imposes both inordinate physical and mental stress constantly upon us, with the result that the weak-minded among us often fall prey to being "brainwashed" — accepting the intended lifestyle and the value framework that goes with it.

Such external control leaves us little opportunity to "think things through," and we end up making artificial, unwise, inaccurate judgments. For some of us, those results can be enduring, even for life, depending on the intensity of the externally-imposed training, and our degree of submissiveness.

I might point out that we all experience such external attempts to control our thinking and behavior in formal schooling and other institutional settings. Mormons don't have a patent on such overt mind control and behaviorism — they just do it with exceptional thoroughness and success.

Interestingly enough, Mitt's industrialist father (who felt his mission was instrumental in molding him) lost his chance to become president over a comment he made to the press that he was "brainwashed" by American military leaders when he visited the Vietnam War zone in the tumultuous 1960's. He was perceived as not tough enough to be president.

It's worth noting that when Mitt went on his mission, he himself was like "thin tissue" (he says) in his appreciation of his Mormon faith. He was thus easily influenced by the carefully-controlled mental and physical regimen of his mission.

I found the LDS mission regimen ungodly, myself, in a way that (among other things) contravened longstanding LDS belief in what is called "free agency" (the same thing as the philosophical term "free will"). Mormon culture outside the "mission field" generally prizes freedom of thought and action, in accord with scriptural guidelines. In the mission field, however — that "theater of operations" outside well-established Mormon culture — such personal freedom, vital to true learning and growth, can be smothered under a code of imposed rules, dictated choices, and required dependency on the mission "parents" (the president and his wife), as well as on young missionaries placed over slightly younger ones to lead, guide, tutor, and yes, control them.

The result, at the time I went, was a two (or two-and-a-half) year virtual hell for those with any reasonable sense of their God-given "agency" and their doctrine-based accountability to God. The mission was designed to be a "spiritual boot-camp" for weeding out compliant future leaders from chaff who refused to go along.

The result, at the time I went, was a two (or two-and-a-half) year virtual hell for those with any reasonable sense of their God-given "agency" and their doctrine-based accountability to God. The mission was designed to be a "spiritual boot-camp" for weeding out compliant future leaders from chaff who refused to go along.Mitt went along, with great skill and apparent enthusiasm.

Junior executives

As Mormon missionaries today continue to walk the world's streets looking like junior executives (in my day, we were mistaken for CIA agents), let me point out that during my mission, I was shocked at the obvious conflict between what I'd learned growing up in the LDS church in Utah and California, and what I was being told was true, orthodox, and expected on my mission in the Great Lakes region of America. They were not one and the same at all — to my mind.

The first allowed broad personal interpretation and application of LDS doctrine as I sought my own understanding and priorities, using the LDS canon as my guide (and my prior commitment and understanding regarding Christ's saving doctrine). The second was a "practical," "business-minded" sales model for converting not just the world to Mormonism, but the missionary himself.

The mission approach at the time was thoroughly based in methods and techniques that emphasized setting measurable goals, achieving measurable results, competing with other missionaries for recognition, and twisting the arm of God to go along (a perversion of true faith).

It's very much the way the whole church operates today at every level (I've learned from my 60-plus years of observing the church from the inside) — but without the invasive 24/7 control typical of the mission field. Local church leaders have less direct influence over each individual (although they often indicate they wish they had more). Even so, the day-to-day relationship of regular members and their local "bureaucratic" leaders is arguably more authoritarian and controlling than that found in any other institution or culture in existence that professes to be Christian.

The reason: the church's corporate "business" model, combined with a claimed automatic right of leaders to divine revelation. Local leaders — as well as a large proportion of the membership — learned this approach on their missions and are simply being true to their training.

I should add that such an authoritarian business management approach, as exists from top to bottom in the church, is alien to scripture and contrary to the principles of salvation for which Christ died. It trivializes — and prostitutes — the very gospel of Christ itself.

I learned this reality — this disparity between reasonable, personal religion and overbearing institutional control — after just a few weeks into my mission in the suburbs of Detroit. I've seen it confirmed repeatedly and unmistakably in the many years since. The church's decidedly "corporate management" model may seem an impressive strength from a worldly institutional perspective, but it's an ecclesiastical disaster, leading all who adopt it, or cater to it, further from Christ and His salvation, not closer.

Positive thinking

In this pragmatic, results-oriented ecclesiastical framework — a framework, as stressed, outside the doctrinal canon of the church — we now take up Mitt's own embrace 45 years ago of what was then called in the mission field "Positive Mental Attitude."

It's a value system that has guided Mitt ever since (and can still be found extensively throughout Mormon culture).

A Positive Mental Attitude was the paramount, defining value in my own mission, as it was in Mitt's. The difference for the two of us is that I rejected it as a perversion of authentic faith in Christ, while Mitt adopted it wholeheartedly, becoming deeply "converted" to it.

What is "PMA," as some call it?

Most of us are familiar with "positive thinking" in one form or another. In its innocuous forms, it's basically the idea of an upbeat, positive outlook, the kind that is helpful in dealing with life's ups and downs.

No one would disparage that kind of cheerful, positive optimism.

But the philosophy of positive thinking is more explicit and far-reaching than that and says in essence, no matter its variations:

"Whatever the mind of man can conceive and believe, it can achieve."

In the late 1930's, at the height of the depression, this philosophy became popular as the centerpiece of Napoleon Hill's best-selling Think and Grow Rich.

This book — with its philosophical groundings in the above article of faith — has served for decades as the conceptual "bible" of the business world, particularly of those who sincerely wish to "grow rich" through dedicated application of the "principle of positive thinking."

Here's the problem:

Here's the problem:The central premise of Think and Grow Rich — belief in auto-suggestive, self-assertive "positive thinking" — is a godless absurdity, and those who accept it as true are self-deluded.

The notion that "whatever" a person can think of and believe strongly enough will come to fruition is not an article of faith at all. It's an article of faithlessness.

It's not a tenet of godly behavior, as some presume, but the very essence of godless behavior. It's the premise of atheism — which literally means "without God."

It suggests we don't need God, that we can "bargain with life on [our] own terms" (to quote from Hill's preface) — accomplishing by ourselves anything we choose.

It verbalizes what those without God want to believe — not what is eternally or intrinsically true.

It's as evil an idea as ever there could be, and it deprives its adherent of God's salvation — which is contingent on submission to His will in all we do, with our whole souls.

Jesus said, "without me ye can do nothing" (John 15:5).

The truth is, nothing we can "conceive and believe" can be done in a way that will please God. We might succeed in doing what we want for a time — to our detriment (for "whatsoever is not of faith is sin"); but we will lose any hope of salvation if we attempt to live consistently in such a godless manner.

Only as we seek to avoid such self-centered, prideful behavior — and instead submit ourselves fully to God, doing His will, His way — can we gain eternal life as promised by scripture (see John 5:19-20,30; 8:28-29; and 14:6).

Nothing in the Bible is more plain.

Go and sell all that thou hast...

So how did Mitt get caught up in such an inherently atheistic way of believing?

From his mission.

Specifically, from a high church leader who recommended the book Think and Grow Rich to the missionaries in Mitt's mission. This same leader — later to become "president of the church" — was not alone in such advocacy. The book — and its philosophy — was rampant throughout the church's missions, since numerous governing "general authorities" believed its pragmatism would help boost the rate of "convert baptisms."

I recall encountering the book and its "positive thinking" frequently among the missionaries and leaders in my own mission. I also recall informing these perverters of faith in God that they were seriously misguided.

Positive thinking — or Positive Mental Attitude — was not true faith, I told them. It was its antithesis.

Thankfully, in today's LDS governing leadership, some express much the same sentiment as I tried to communicate. But back in the 1960's, few, if any, did. Think and Grow Rich was held in highest esteem in the church, and "positive thinking" was so popular in the church, I encountered it casually when I was home from my first year of college and a speaker gave a well-attended seminar on it at our local "stake center." This was a year before my mission.

Imagine God looking down upon such profane evil in an "ecclesiastical" setting.

Back to Mitt. According to a missionary companion, Mitt complied with the above church leader's counsel and took the book to heart as a guide for success with anything and everything — even telling a missionary conference, Mitt wrote in his journal, "we can obtain anything we want in life — if we want it badly enough," a summation of Hill's book.

Mitt traveled the mission preaching that message to other missionaries to help them "reach their goals."

At one point, Mitt (with two associates) created a pamphlet based on Hill's teachings and gave it to the mission's 200 other missionaries when Mitt and another "assistant to the president" ran the mission in the absence of the mission president — who had returned home for two months. During that time, Mitt "cracked the whip," an associate commented, and led the mission to more than doubling its baptism rate, "proving" to himself and others the value of positive thinking.

The idea of mimicking business principles in "selling" the LDS church's message clearly appealed to Mitt, and in turn helped form his most basic values.

Interestingly, at BYU shortly after his mission, Mitt organized a telethon using the sales techniques he gleaned from Think and Grow Rich, raising a million dollars for the university in the process and setting a pattern for his life's work.

Observations

I have a whole file of references, quotes, testimonials, and other information to support the above hypothesis: that Mitt is a deeply-committed positive thinker who sincerely believes such a godless "business" approach is the practical foundation for all meaningful success — particularly for Mormons who paradoxically believe they are on God's errand in making the world better.

Nothing could be more mistaken, of course, as a philosophy for public or personal good.

But this hypothesis explains Mitt's thoroughgoing pragmatism; his meandering relativism; his superficial view of God and His teachings; his fabled lack of a discernible "moral core"; his bureaucratic, corporate-minded tendencies; his preoccupation with what can be measured and counted; his lifelong obsession with thinking big about himself and his abilities; and his unprincipled inclination to compromise.

But this hypothesis explains Mitt's thoroughgoing pragmatism; his meandering relativism; his superficial view of God and His teachings; his fabled lack of a discernible "moral core"; his bureaucratic, corporate-minded tendencies; his preoccupation with what can be measured and counted; his lifelong obsession with thinking big about himself and his abilities; and his unprincipled inclination to compromise.He's just doing what Mr. Hill made sound true and attractive in his influential guide to selling oneself and one's ideas, a philosophy Mitt learned in the controlling crucible of his LDS mission.

Never mind that Mitt's own church contradicts such thinking and behavior in its canon, in a strongly worded condemnation of preoccupation with worldly success and the notion of "selling oneself" — in words that seem tailored to Mitt himself:

-

For behold, ye do love money, and your substance, and your fine apparel, and the adorning of your churches, more than ye love the poor and the needy, the sick and the afflicted.

O ye pollutions, ye hypocrites, ye teachers, who sell yourselves for that which will canker, why have ye polluted the holy church of God? Why are ye ashamed to take upon you the name of Christ? Why do ye not think that greater is the value of an endless happiness than that misery which never dies — because of the praise of the world?

Why do ye adorn yourselves with that which hath no life, and yet suffer the hungry, and the needy, and the naked, and the sick and the afflicted to pass by you, and notice them not?

Yea, why do ye build up your secret abominations to get gain.... (Mormon 8:37-40, emphasis added)

I raise these issues and facts not to disparage Mitt, nor even to dissuade those who are determined to vote for him on purely pragmatic grounds — but to educate interested Americans in the connection between Mitt and his mission, which went a long way toward "making the man." It's a connection that's vital to getting inside Mitt's mind.

In the meantime, I can't get out of my own mind an image of the quintessential positive thinker, Stuart Smalley, portrayed by now-Senator Al Franken years ago on Saturday Night Live, who would end each satirical segment by saying — with self-affirming sincerity into a mirror: "I'm good enough, I'm smart enough, and doggone it, people like me."

Such is the image-conscious world of self-deception conjured by all who seriously subscribe to positive thinking.

© Stephen Stone