The rise of conservatism and the decline of liberalism

Fred Hutchison, RenewAmerica analyst

Originally published February 13, 2007

Originally published February 13, 2007

Democratic politics is ultimately a battle of worldviews. A rising worldview will eventually prevail over a declining worldview in elections and in the market place of ideas. This essay will review the rise of conservatism and the decline of liberalism over the last fifty years from the standpoint of the slowly changing worldviews of Americans.

Self-evident truths

All worldviews begin with presuppositions, or things assumed. Presuppositions are taken on faith or as self-evident truths. Self-evident truths are ideas that one deems unthinkable to doubt or question. Unfortunately, the self-evident truths of one worldview sometimes clash with the self-evident truths of another worldview. How can this be? How can a truth be self-evident to one rational man and not self-evident to another?

The best way to explain this conundrum is to give an example of contradictory self-evident truths. First, I shall present the birth of one of the "self evident truths" of liberalism. This "truth" came into the world only 150 years ago. Before then it was not self-evident to anyone living in Christian Europe.

The birth of liberalism

As a young misfit, Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) was a restless wanderer, never finding a place where he could comfortably settle into human society. Unable to adhere to friendships because he was a self-absorbed misanthrope and was hypersensitive to the point of paranoia, he turned to solitary walks in nature to find refuge and solace. Historian Will Durant described his turn to nature:

"Uncomfortable with the society of educated men, shy and wordless before beautiful women, he was happy when alone with woods and fields, water and sky. He made nature his confidante, and in silent speech told her his loves and dreams. He imagined that the moods of Nature entered at times into a mystic accord with his own."

During the summer of 1749, Rousseau made several ten-mile round trip walks between Paris and Vincennes to visit Denis Diderot, who was in jail. During one of those walks, he had a mystical experience:

"All at once I felt myself dazzled by a thousand sparkling lights. Crowds of vivid ideas thronged into my mind with a force and confusion that threw me into unspeakable agitation. I felt my head whirling in a giddiness like that of intoxication. A violent palpitation oppressed me. Unable to walk for difficulty in breathing, I sank down under one of the trees by the road, and passed half an hour there in such a condition of excitement that I rose and saw that the front of my waistcoat was thick with tears.... Ah, if ever I could have written a quarter of what I saw and felt under that tree, with what clarity I should have brought out all the contradictions of our social system! With what simplicity I should have demonstrated that man is by nature good, and that only his institutions have made him bad!"

As Rousseau sat under that tree on the road to Vincennes, liberalism was born. The words in his fevered mind "Man is by nature good and only his institutions have made him bad" were to be a first principle of the liberal worldview. Millions of liberals in the two centuries to follow believed without reservation that man is inherently good and that society is entirely responsible for making men bad.

As Rousseau sat under that tree on the road to Vincennes, liberalism was born. The words in his fevered mind "Man is by nature good and only his institutions have made him bad" were to be a first principle of the liberal worldview. Millions of liberals in the two centuries to follow believed without reservation that man is inherently good and that society is entirely responsible for making men bad.

Rousseau as prophet

Was Rousseau the prophet of a new religion of liberal humanism? After all, he received his message by a mystical epiphany when he was in an ecstatic trance. Europeans who were inclined toward the budding Romantic movement sometimes received his message by a leap of faith as though they were having a religious conversion.

What kind of "prophet" was this? Paul Johnson, in his book Intellectuals, depicted Rousseau as a man of evil character, and a misanthrope who was extremely obnoxious to those who tried to befriend him. He suffered paranoia and imagined conspiracies against him. False accusations flew from his poisoned pen to slander people who wished him well. Rousseau was the perfect prototype of the liberal who loves mankind in the abstract, but hates people in the particular.

Rousseau was prolific in fathering illegitimate children, all of whom he put in foundling homes or orphanages. In spite of his famous sentimentality, he was devoid of tender feelings for his own children. Rousseau's tender feelings were limited to "mankind," to nature, to music, and to his reflections about himself and his feelings. His friends expected no tenderness, but only hard-hearted rebuffs.

In a world vexed by inordinate self-love, Rousseau carried his love affair with himself to new heights, if his autobiography is any indicator. This is not the profile of a prophet. It is the profile of a narcissist, a libertine, a heretic, and a man of reprobate mind.

What kind of experience did Rousseau have as he sat under the tree on the road to Vincennes? He was in a state of confusion, agitation, giddiness, and emotional intoxication. He saw strange lights, had violent heart palpitations, and was light-headed, physically weak, and short of breath, as though he was having a panic attack. He wept until his coat was wet, as though he was in a state of hysteria. These symptoms are not typical of true spiritual revelations. They are typical of delusions.

Rousseau as philosopher

Rousseau as philosopher

Rousseau's explanation of why it is society that corrupts man and not man who corrupts society does not make sense. Rousseau thought that the acquisition of private property was the first step in the corruption of the "noble savage." But if the savage was noble and inherently good, why would mere property introduce corruption into his heart? Why would not the good savage regard the property as an opportunity to do good to others and to make life better for himself? An inherently good being is not going to create a bad society. "A good tree cannot bring forth bad fruit" (Matthew 7:18).

Rousseau never explained how a civilization can come into being if civilization makes man worse. Surely the early steps toward civilization must have a positive effect on man to provide impetus to the monumental project of building cities. If civilization makes men worse, why are civilized men so civil and barbarians so rude? Why was the civilized Voltaire easier to live with than the obstreperous Rousseau, who was the child of nature?

Why have so few liberals asked themselves these questions? How can they spend a lifetime observing the tenacity with which men cling to their vice, folly, and malice without having doubts about the inherent goodness of man? Could it be that liberalism is a romantic enchantment and an emotional seduction that bypasses the mind?

During my teen years, I got my first look at the enchantment of liberalism. I observed a vein of hysteria and irrationality running through liberalism along with a fatal habit of wishful thinking and a denial of reality. I resolved never to be a liberal.

Five conservative philosophies

A cluster of conservative philosophies is held together by their mutual rejection of the premier liberal heresy that deceived Rousseau as he sat under the tree. Let us consider five major camps of conservatives.

1. Christian conservatives believe that man is fallen and that every sinner requires a divine savior to lift him out of the bondage to sin. Society is corrupt to the extent that fallen man has corrupted it. Men are sometimes corrupted by society because the temptations of the city entice man's sinful appetites and propensities.

The ruler bears the sword to restrain human depravity and thereby makes civil order possible. Christian conservatives insist that a free republic cannot long survive if it is overrun with vice, immorality, perversion, and disrespect for human life. God's blessing is upon the family, and the decline of the family must lead to the decline of the nation.

2. Traditionalist conservatives believe that man is a contradiction. The threads of the social fabric restrain man from following his dark side and encourage him to follow the angels of his better nature. The social fabric is spun through the accumulated wisdom of many generations.

Liberal reforms and social engineering projects rend the delicate social fabric and do great damage to civilized society. Traditionalist conservatives often are drawn into political action to protect society from the destructive "reforms" of liberals.

The heart of the traditionalist is with the local community and venerable traditions of family, neighborhood, community, and church. Traditionalists honor the flag, the Constitution, and the founding fathers, and are deeply patriotic about America. Southern traditionalists add the romantic ideals of blood and soil, hospitality, charm and grace, and the code of gallantry of the Southern gentleman to the complex mixture of traditionalism.

The heart of the traditionalist is with the local community and venerable traditions of family, neighborhood, community, and church. Traditionalists honor the flag, the Constitution, and the founding fathers, and are deeply patriotic about America. Southern traditionalists add the romantic ideals of blood and soil, hospitality, charm and grace, and the code of gallantry of the Southern gentleman to the complex mixture of traditionalism.

3. Neo-conservatives generally agree that man is a contradiction, but the focus of their interest is with the human mind instead of the social fabric. "Neo-cons" advocate a return to the literary and intellectual classics of the Western cultural heritage because they care deeply about the human mind and high culture. Instead of focusing on the local community, neo-cons seek a community of minds seasoned by high culture. Their love of excellence has a counterpart in their hatred of mediocrity and cultural decadence. They criticize postmodern liberals for dismantling the intellectual heritage of the West and for breeding a wretched and uncivilized mediocrity.

Whereas traditionalists lament the decline of courtesy, civility, gallantry, grace, and charm, neo-cons lament the decline of intelligent and culturally sophisticated conversation. A well-educated intelligence and the seasoning of a high culture is essential to the full flourishing of human nature in community.

Neo-cons advocate a strong military and police force to defend civilization from barbarians of both the foreign and domestic kind, and believe the defense of Western civilization requires a commitment that goes beyond the needs of national defense. Neo-cons replace the older generation of conservative anti-communists in the battle against cosmic evil and the enemies of civilization. Instead of fighting the fading threat of communism, they are exposing the threat of Muslim terrorism, genocidal Islamic regimes, and Taliban-style enemies of the human mind, and advocating an aggressive response.

Neo-cons have no aversion to the social programs of the federal government – which places them somewhat at odds with traditionalist and libertarian conservatives.

4. Natural law conservatives stress that man has an inherent nature and a person is only good to the extent he adheres to the design of that nature. Evil men behave in a manner contrary to their own nature, they believe. Natural law conservatives love the classical Aristotelian virtues that are based on defining virtuous thought and virtuous action in terms of man's true design. They reject the liberal view of a spontaneous goodness found in the man of nature who is uncorrupted by civilization. Quite to the contrary, true virtue is the fruit of a long developmental process requiring much personal discipline. The quest is long and hard for man to become what he was designed to be.

Natural law conservatives are particularly contemptuous of the liberal claim that civilization alone has corrupted man and that only government reform can make man whole. Man is born with an inherent nature, and government cannot change that nature. However, civilization is the product of human virtue and therefore, civilization is the natural abode of man. Civilized society is the only decent life for a virtuous man. However, civilization can be an ordeal for those individuals who refuse to develop virtue so they can contribute to the commonweal according to their individual design. Civilized society is difficult to endure for narcissists and misanthropes like Rousseau.

5. Libertarian conservatives believe that man develops his powers, talents, and virtues through the freedom of the individual. Statism and creeping socialism of the kind liberals advocate crush the good impulses of the individual and nourish the dark impulses of tyranny and of perverse delight in mind-control, social control, and social engineering by men with too much power.

5. Libertarian conservatives believe that man develops his powers, talents, and virtues through the freedom of the individual. Statism and creeping socialism of the kind liberals advocate crush the good impulses of the individual and nourish the dark impulses of tyranny and of perverse delight in mind-control, social control, and social engineering by men with too much power.

Libertarians find their strongest link with other conservatives in their defense of free enterprise, their contributions to the field of economics, their critique of socialism and statism, and their embrace of the constitutional limits of government power. Their robust defense of the mind and will of the individual against the tyranny of the collective is indispensable for a world in which liberals dominate the great institutions.

Although I admire the other four camps of conservatism, I have reservations about libertarianism because of its constricted view of human nature and its rejection of the universal moral law. Some libertarians seem to think that the free will and the rational mind of the individual are the only things that have ontological being and that all else is an illusion.

But quite to the contrary, human nature is a complex bundle of many faculties. Those who only recognize the rational mind and the free will as worthy human faculties do not understand what it means to be human.

The mind and will are crucial to being human and have an important appointed role to play, of course. However, there are natural limits to the natural jurisdiction and functions of the mind and the will. Moral constraints must be applied to what one may say and do. These wholesome boundaries are sometimes ignored by those libertarians who place their quest for unrestrained atomistic individualism above all other considerations. While a moderate amount of individualism is liberating and energizing, hyper-individualism and atomistic individualism are destructive.

The conservative advantage

Conservatism has always been superior to liberalism in the correspondence of conservative ideas to the real world of people and society. Liberal progressives have always been crippled by a discontinuity between theory and practice. For example, in order to survive in the real world, liberals have to behave as though man is not inherently good, while denying that their behavior contradicts a first principle of their worldview.

Liberals have had remarkable historical success is glossing over the internal contradictions of their ideas – such as the contradictions that Rousseau never bothered to explain. Liberals achieved this conceptual tour de force with their romantic belief in the inevitability of progress leading to a future utopia and their sentimental belief in the innate goodness of man. As a result of this romantic triumph of feelings over reason, the various strands of liberalism held together for two centuries.

Interestingly, liberalism coalesced as the political branch of the Romantic movement. Liberalism retained its romantic appeal as late as the presidency of John F. Kennedy. In 1969, art historian Kenneth Clark said that "we are the nearly bankrupt heirs" of the Romantic movement. At that time, the liberal worldview was already in crisis. Liberalism might not survive the death of the Romantic movement.

Interestingly, liberalism coalesced as the political branch of the Romantic movement. Liberalism retained its romantic appeal as late as the presidency of John F. Kennedy. In 1969, art historian Kenneth Clark said that "we are the nearly bankrupt heirs" of the Romantic movement. At that time, the liberal worldview was already in crisis. Liberalism might not survive the death of the Romantic movement.

The liberal worldview has been unraveling in Europe since 1920 and in America since 1968-70. In contrast, the five camps of conservatives still adhere to the presuppositions of their worldview. Their faithful adherence to first principles gives them a logical consistency and coherence that liberalism no longer has. This is the conservative advantage.

The religious implications of liberalism

The liberal worldview consists of four quasi-religious presuppositions: 1) the belief in the inherent goodness of man, 2) the belief that society is the source of human evil, 3) the belief in the inevitability of progress toward a future utopia, and 4) the belief that government can play a redemptive and messianic role for mankind.

These four quasi-religious beliefs contradict the teachings of doctrinally orthodox Christianity. Some theologians classify these beliefs as heresies because they eliminate the need of sinners for a divine savior. Liberals have adhered to the four heresies for two centuries with a quasi-religious faith. For some liberals, the quasi-religion of liberal humanism is a substitute for Christianity. That is why liberal idealism has had a messianic tone. Other liberals have grafted the four heresies into some branches of Christianity and produced the pseudo-religion of liberal Protestantism.

Religious experimentation

During the French Revolution (1779-1799), Christianity was suppressed and various experiments were made in developing substitute religions. For example, the Cathedral of Notre Dame was used to celebrate a religion of reason and nature under the aegis of pagan gods. During the reign of terror, Robespierre established a state religion of Deism.

In 1799, Napoleon decided that the newly-invented religions of liberalism were failures. He re-established Christianity not because he was a believer, but because he saw Christianity as indispensable to the stability of the realm. The common people, exhausted by revolution and weird religious and political experiments, gratefully flooded back into the churches.

In England, liberals realized that they could not stop Christianity, so they concentrated on subverting it with liberalism and using Christian institutions to propagate liberal ideas. As a result of the partial success and partial failure of this agenda, a spectrum of theology exists in the churches in England and America ranging from liberal to conservative.

Parallels of theology and politics

Parallels of theology and politics

It is no accident that the majority of church-going theological liberals are also political liberals, and the majority of church-going theological conservatives are also political conservatives. After all, theology plays a part in developing the first principles of worldviews, and worldviews lie at the root of political philosophy.

It is no accident that the historical rise of doctrinally conservative Christian denominations and sects roughly corresponds with the rise of political conservatism in America (1950-2000). It is also no accident that the decline of liberal Protestantism (1965-2000) roughly corresponds with the time of crisis in the liberal worldview (1968-2000).

The lobotomy of liberalism

Postmodern liberals have cut themselves off from the four core beliefs of the liberal worldview. As a result, liberalism is psychologically and intellectually disintegrating. The intellectual disintegration of liberalism is evidenced by 1) group think, 2) the inability to formulate a logical argument or develop a positive program, 3) the rise of left-wing conspiracy theories, 4) the use of indoctrination techniques in schools, 5) the demonization of opponents, 6) the shouting down of opponents, and 7) paranoid obsessions with catastrophe, such as the post-nuclear Armageddon fantasies of Hollywood and the faddish warnings of environmental catastrophe of junk science.

A person who is watching the collapse of his worldview thinks the fabric of the world is coming apart at the seams – and tends to have illusions of impending catastrophes. This blinds him to real dangers. If one is obsessed with global warming hype, for example, he will not take seriously the real threat of Muslim terrorism.

The disappearance of reason

Why cannot liberals think logically anymore? Did the lobotomy of liberalism cut them off from reason?

All logic must begin with presuppositions or first principles. Postmodern liberals have thrown away the presuppositions of their worldview. In a prior essay, I identified the three common approaches to thinking that reject the use of presuppositions. My thesis was that all of these substitute approaches must, of necessity, lead to logical fallacies.

Descent into nihilism

Leo Strauss (1899-1973), the father of neo-conservatism, predicted that liberalism must eventually give way to relativism and that relativism must eventually give way to nihilism. Nihilism is the final stage of negation after all the strands of a political philosophy have been peeled away.

Leo Strauss (1899-1973), the father of neo-conservatism, predicted that liberalism must eventually give way to relativism and that relativism must eventually give way to nihilism. Nihilism is the final stage of negation after all the strands of a political philosophy have been peeled away.

As one moves left through the spectrum of beliefs in the Democratic party, one will find relativism just to the left of center. The next step to the left on the liberal rainbow is skepticism. Cynicism follows skepticism, and nihilism follows cynicism. Michael Moore, who produces dishonest anti-American propaganda, is a blackguard of cynicism. To the left of Moore, one finds the fiends of nihilism. The land of intellectual nihilism is reserved for haters, slanderers, conspiracy theorists, and embittered and hysterical fools like Cindy Sheehan and the bloggers of Moveon.org. Interestingly, the malice and paranoia of Sheehan is reminiscent of Rousseau, the father of liberalism.

The Christopher Hitchens phenomenon

Christopher Hitchens was once an important voice of the far left, but is now disillusioned with the left. He remains an atheist and retains some of his roots in Enlightenment and Marxist thought. In practice, he seems to be an occasional neo-con fellow traveler. He does not embrace anything like a conservative worldview, but he finds that on the whole, conservative thought is more rational, more coherent, and less self-contradictory than the woozy world of left-think.

Having fled the intellectually sinking ship of liberalism, Hitchens has found temporary refuge on board U.S.S. Conservatism. He is seasick, hates the food, and has sardonic words of contempt for passengers and crew, but he knows the ship is seaworthy. He can survive upon the alien ship of conservatism and live a life banished at sea, until he can find land congenial for his foot to step on.

Hitchens amuses himself by ridiculing the stout crew of U.S.S. Conservatism and waxing poetic about the fatal irony of his unhappy voyage. He has been floated on foreign waters surrounded by uncongenial company for some fifteen years, finding consolation in the fiery missiles he sends out against a liberalism gone mad. He is deeply embittered that his natural home of liberalism is no longer fit for a sane man to live in.

The wrecked ship of liberalism has many refugees floating upon the flotsam and jetsam of the intellectual seas. What is it about Hitchens that makes him interesting? His intellectual wits have noticeably sharpened since he has been lost at sea, floating on a ship built upon presuppositions that he rejects. Hitchens has become intellectually interesting in ways he was not when he strutted upon the proud land of left-world.

Worldviews and the Hitchens syndrome

How are we to understand the phenomenon of Hitchens sharpening his wits in intellectual exile? It holds a key to understanding why the rising intellectual powers of the conservative movement have swamped the intellectually bankrupt thought of the left.

Man cannot function without worldviews, but some aging worldviews have a tendency toward gradual constriction until there is not enough room for the mind to maneuver. The Christian worldview resisted this tendency to the extent that it left a space for a transcendent realm that is outside this world.

Man cannot function without worldviews, but some aging worldviews have a tendency toward gradual constriction until there is not enough room for the mind to maneuver. The Christian worldview resisted this tendency to the extent that it left a space for a transcendent realm that is outside this world.

When a collapsing worldview begins to resemble a closed system, the human mind shuts down. Reason cannot exist within a closed system. However, if one briefly steps out of his constricted worldview and visits another, the mind is momentarily rejuvenated. That is why Hitchen's voyage on U.S.S. Conservatism revived his rational faculties.

Hitchens and Jennings

Just before the first Persian Gulf war (1990-91), Christopher Hitchens and the late Peter Jennings of ABC News were traveling together towards Kuwait. Hitchens said that the measure of success would now be, not the recovery of Kuwait, but the replacement of the Baathist order. Hitchens said, "I shall never forget his response which was journalist to journalist, 'That is only if we say so.'" (Source: Theater of War, a book review by Hitchens in the Claremont Review of Books, Winter, 2006-7)

Jennings thought the public conception of the Iraq war would be determined by leading liberal journalists. He effectively said, "People will think what our clique tells them to think." Journalism had been replaced by indoctrination by a small elite clique.

Hitchens had to either check his intellect at the door and join the group-think clique who sought to indoctrinate the public, or flee the land of the liberals.

Conservatism and the Hitchens syndome

The noticeable sharpening of Hitchen's wits points us to another conservative intellectual advantage. Every conservative intellectual has debated with conservatives of other camps. When I was in college, traditionalists were constantly debating libertarians. Now, the Christian conservatives are debating the neo-cons.

These constant internecine debates have sharpened the wits of every conservative thinker. I like to call it the "Hitchens syndrome." The intellectual edge gives conservatives special advantages in exposing the decaying worldview of liberals.

Debates with liberals have forced conservatives to constantly think about first principles. The worldview of liberalism is so different from the worldview of conservatism that it is extremely difficult to come to agreement, or even understand what the other person is saying. Sometimes the only way forward in such a situation is to return to conservative first principles and critique liberal first principles. Through such exercises, liberals have unwittingly helped conservatives cling tightly to their first principles, while they themselves were losing their grip on their own first principles.

A time of upheaval

A time of upheaval

When a person changes his worldview, he goes through a time of personal upheaval like Rousseau and Christopher Hitchens. All his ideas, his interpretations of events, and agendas must be revisited, deconstructed, and reconstructed. All settled ground has collapsed, and new footholds must be sought.

When a society changes its dominant worldview, that society must go through a time of upheaval. As conservatism replaces liberalism as the dominant worldview of the society, many people will be confused and alienated. The rage and paranoia of the left are an important indicator that we are entering a time of trouble. As Bette Davis said in the movie All About Eve, "Fasten your seat belts. It is going to be a bumpy ride."

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

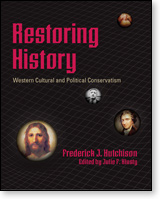

I first became acquainted with Fred Hutchison in December 2003, when he contacted me about an article he was interested in writing for RenewAmerica about Alan Keyes. From that auspicious moment until God took him a little more than six years later, we published over 200 of Fred's incomparable essays — usually on some vital aspect of the modern "culture war," written with wit and disarming logic from Fred's brilliant perspective of history, philosophy, science, and scripture.

It was obvious to me from the beginning that Fred was in a class by himself among American conservative writers, and I was honored to feature his insights at RA.

I greatly miss Fred, who died of a brain tumor on August 10, 2010. What a gentle — yet profoundly powerful — voice of reason and godly truth! I'm delighted to see his remarkable essays on the history of conservatism brought together in a masterfully-edited volume by Julie Klusty. Restoring History is a wonderful tribute to a truly great man.

The book is available at Amazon.com.

© Fred Hutchison

June 27, 2013

Originally published February 13, 2007

Originally published February 13, 2007Democratic politics is ultimately a battle of worldviews. A rising worldview will eventually prevail over a declining worldview in elections and in the market place of ideas. This essay will review the rise of conservatism and the decline of liberalism over the last fifty years from the standpoint of the slowly changing worldviews of Americans.

Self-evident truths

All worldviews begin with presuppositions, or things assumed. Presuppositions are taken on faith or as self-evident truths. Self-evident truths are ideas that one deems unthinkable to doubt or question. Unfortunately, the self-evident truths of one worldview sometimes clash with the self-evident truths of another worldview. How can this be? How can a truth be self-evident to one rational man and not self-evident to another?

The best way to explain this conundrum is to give an example of contradictory self-evident truths. First, I shall present the birth of one of the "self evident truths" of liberalism. This "truth" came into the world only 150 years ago. Before then it was not self-evident to anyone living in Christian Europe.

The birth of liberalism

As a young misfit, Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) was a restless wanderer, never finding a place where he could comfortably settle into human society. Unable to adhere to friendships because he was a self-absorbed misanthrope and was hypersensitive to the point of paranoia, he turned to solitary walks in nature to find refuge and solace. Historian Will Durant described his turn to nature:

"Uncomfortable with the society of educated men, shy and wordless before beautiful women, he was happy when alone with woods and fields, water and sky. He made nature his confidante, and in silent speech told her his loves and dreams. He imagined that the moods of Nature entered at times into a mystic accord with his own."

During the summer of 1749, Rousseau made several ten-mile round trip walks between Paris and Vincennes to visit Denis Diderot, who was in jail. During one of those walks, he had a mystical experience:

"All at once I felt myself dazzled by a thousand sparkling lights. Crowds of vivid ideas thronged into my mind with a force and confusion that threw me into unspeakable agitation. I felt my head whirling in a giddiness like that of intoxication. A violent palpitation oppressed me. Unable to walk for difficulty in breathing, I sank down under one of the trees by the road, and passed half an hour there in such a condition of excitement that I rose and saw that the front of my waistcoat was thick with tears.... Ah, if ever I could have written a quarter of what I saw and felt under that tree, with what clarity I should have brought out all the contradictions of our social system! With what simplicity I should have demonstrated that man is by nature good, and that only his institutions have made him bad!"

As Rousseau sat under that tree on the road to Vincennes, liberalism was born. The words in his fevered mind "Man is by nature good and only his institutions have made him bad" were to be a first principle of the liberal worldview. Millions of liberals in the two centuries to follow believed without reservation that man is inherently good and that society is entirely responsible for making men bad.

As Rousseau sat under that tree on the road to Vincennes, liberalism was born. The words in his fevered mind "Man is by nature good and only his institutions have made him bad" were to be a first principle of the liberal worldview. Millions of liberals in the two centuries to follow believed without reservation that man is inherently good and that society is entirely responsible for making men bad.Rousseau as prophet

Was Rousseau the prophet of a new religion of liberal humanism? After all, he received his message by a mystical epiphany when he was in an ecstatic trance. Europeans who were inclined toward the budding Romantic movement sometimes received his message by a leap of faith as though they were having a religious conversion.

What kind of "prophet" was this? Paul Johnson, in his book Intellectuals, depicted Rousseau as a man of evil character, and a misanthrope who was extremely obnoxious to those who tried to befriend him. He suffered paranoia and imagined conspiracies against him. False accusations flew from his poisoned pen to slander people who wished him well. Rousseau was the perfect prototype of the liberal who loves mankind in the abstract, but hates people in the particular.

Rousseau was prolific in fathering illegitimate children, all of whom he put in foundling homes or orphanages. In spite of his famous sentimentality, he was devoid of tender feelings for his own children. Rousseau's tender feelings were limited to "mankind," to nature, to music, and to his reflections about himself and his feelings. His friends expected no tenderness, but only hard-hearted rebuffs.

In a world vexed by inordinate self-love, Rousseau carried his love affair with himself to new heights, if his autobiography is any indicator. This is not the profile of a prophet. It is the profile of a narcissist, a libertine, a heretic, and a man of reprobate mind.

What kind of experience did Rousseau have as he sat under the tree on the road to Vincennes? He was in a state of confusion, agitation, giddiness, and emotional intoxication. He saw strange lights, had violent heart palpitations, and was light-headed, physically weak, and short of breath, as though he was having a panic attack. He wept until his coat was wet, as though he was in a state of hysteria. These symptoms are not typical of true spiritual revelations. They are typical of delusions.

Rousseau as philosopher

Rousseau as philosopherRousseau's explanation of why it is society that corrupts man and not man who corrupts society does not make sense. Rousseau thought that the acquisition of private property was the first step in the corruption of the "noble savage." But if the savage was noble and inherently good, why would mere property introduce corruption into his heart? Why would not the good savage regard the property as an opportunity to do good to others and to make life better for himself? An inherently good being is not going to create a bad society. "A good tree cannot bring forth bad fruit" (Matthew 7:18).

Rousseau never explained how a civilization can come into being if civilization makes man worse. Surely the early steps toward civilization must have a positive effect on man to provide impetus to the monumental project of building cities. If civilization makes men worse, why are civilized men so civil and barbarians so rude? Why was the civilized Voltaire easier to live with than the obstreperous Rousseau, who was the child of nature?

Why have so few liberals asked themselves these questions? How can they spend a lifetime observing the tenacity with which men cling to their vice, folly, and malice without having doubts about the inherent goodness of man? Could it be that liberalism is a romantic enchantment and an emotional seduction that bypasses the mind?

During my teen years, I got my first look at the enchantment of liberalism. I observed a vein of hysteria and irrationality running through liberalism along with a fatal habit of wishful thinking and a denial of reality. I resolved never to be a liberal.

Five conservative philosophies

A cluster of conservative philosophies is held together by their mutual rejection of the premier liberal heresy that deceived Rousseau as he sat under the tree. Let us consider five major camps of conservatives.

1. Christian conservatives believe that man is fallen and that every sinner requires a divine savior to lift him out of the bondage to sin. Society is corrupt to the extent that fallen man has corrupted it. Men are sometimes corrupted by society because the temptations of the city entice man's sinful appetites and propensities.

The ruler bears the sword to restrain human depravity and thereby makes civil order possible. Christian conservatives insist that a free republic cannot long survive if it is overrun with vice, immorality, perversion, and disrespect for human life. God's blessing is upon the family, and the decline of the family must lead to the decline of the nation.

2. Traditionalist conservatives believe that man is a contradiction. The threads of the social fabric restrain man from following his dark side and encourage him to follow the angels of his better nature. The social fabric is spun through the accumulated wisdom of many generations.

Liberal reforms and social engineering projects rend the delicate social fabric and do great damage to civilized society. Traditionalist conservatives often are drawn into political action to protect society from the destructive "reforms" of liberals.

The heart of the traditionalist is with the local community and venerable traditions of family, neighborhood, community, and church. Traditionalists honor the flag, the Constitution, and the founding fathers, and are deeply patriotic about America. Southern traditionalists add the romantic ideals of blood and soil, hospitality, charm and grace, and the code of gallantry of the Southern gentleman to the complex mixture of traditionalism.

The heart of the traditionalist is with the local community and venerable traditions of family, neighborhood, community, and church. Traditionalists honor the flag, the Constitution, and the founding fathers, and are deeply patriotic about America. Southern traditionalists add the romantic ideals of blood and soil, hospitality, charm and grace, and the code of gallantry of the Southern gentleman to the complex mixture of traditionalism.3. Neo-conservatives generally agree that man is a contradiction, but the focus of their interest is with the human mind instead of the social fabric. "Neo-cons" advocate a return to the literary and intellectual classics of the Western cultural heritage because they care deeply about the human mind and high culture. Instead of focusing on the local community, neo-cons seek a community of minds seasoned by high culture. Their love of excellence has a counterpart in their hatred of mediocrity and cultural decadence. They criticize postmodern liberals for dismantling the intellectual heritage of the West and for breeding a wretched and uncivilized mediocrity.

Whereas traditionalists lament the decline of courtesy, civility, gallantry, grace, and charm, neo-cons lament the decline of intelligent and culturally sophisticated conversation. A well-educated intelligence and the seasoning of a high culture is essential to the full flourishing of human nature in community.

Neo-cons advocate a strong military and police force to defend civilization from barbarians of both the foreign and domestic kind, and believe the defense of Western civilization requires a commitment that goes beyond the needs of national defense. Neo-cons replace the older generation of conservative anti-communists in the battle against cosmic evil and the enemies of civilization. Instead of fighting the fading threat of communism, they are exposing the threat of Muslim terrorism, genocidal Islamic regimes, and Taliban-style enemies of the human mind, and advocating an aggressive response.

Neo-cons have no aversion to the social programs of the federal government – which places them somewhat at odds with traditionalist and libertarian conservatives.

4. Natural law conservatives stress that man has an inherent nature and a person is only good to the extent he adheres to the design of that nature. Evil men behave in a manner contrary to their own nature, they believe. Natural law conservatives love the classical Aristotelian virtues that are based on defining virtuous thought and virtuous action in terms of man's true design. They reject the liberal view of a spontaneous goodness found in the man of nature who is uncorrupted by civilization. Quite to the contrary, true virtue is the fruit of a long developmental process requiring much personal discipline. The quest is long and hard for man to become what he was designed to be.

Natural law conservatives are particularly contemptuous of the liberal claim that civilization alone has corrupted man and that only government reform can make man whole. Man is born with an inherent nature, and government cannot change that nature. However, civilization is the product of human virtue and therefore, civilization is the natural abode of man. Civilized society is the only decent life for a virtuous man. However, civilization can be an ordeal for those individuals who refuse to develop virtue so they can contribute to the commonweal according to their individual design. Civilized society is difficult to endure for narcissists and misanthropes like Rousseau.

5. Libertarian conservatives believe that man develops his powers, talents, and virtues through the freedom of the individual. Statism and creeping socialism of the kind liberals advocate crush the good impulses of the individual and nourish the dark impulses of tyranny and of perverse delight in mind-control, social control, and social engineering by men with too much power.

5. Libertarian conservatives believe that man develops his powers, talents, and virtues through the freedom of the individual. Statism and creeping socialism of the kind liberals advocate crush the good impulses of the individual and nourish the dark impulses of tyranny and of perverse delight in mind-control, social control, and social engineering by men with too much power.Libertarians find their strongest link with other conservatives in their defense of free enterprise, their contributions to the field of economics, their critique of socialism and statism, and their embrace of the constitutional limits of government power. Their robust defense of the mind and will of the individual against the tyranny of the collective is indispensable for a world in which liberals dominate the great institutions.

Although I admire the other four camps of conservatism, I have reservations about libertarianism because of its constricted view of human nature and its rejection of the universal moral law. Some libertarians seem to think that the free will and the rational mind of the individual are the only things that have ontological being and that all else is an illusion.

But quite to the contrary, human nature is a complex bundle of many faculties. Those who only recognize the rational mind and the free will as worthy human faculties do not understand what it means to be human.

The mind and will are crucial to being human and have an important appointed role to play, of course. However, there are natural limits to the natural jurisdiction and functions of the mind and the will. Moral constraints must be applied to what one may say and do. These wholesome boundaries are sometimes ignored by those libertarians who place their quest for unrestrained atomistic individualism above all other considerations. While a moderate amount of individualism is liberating and energizing, hyper-individualism and atomistic individualism are destructive.

The conservative advantage

Conservatism has always been superior to liberalism in the correspondence of conservative ideas to the real world of people and society. Liberal progressives have always been crippled by a discontinuity between theory and practice. For example, in order to survive in the real world, liberals have to behave as though man is not inherently good, while denying that their behavior contradicts a first principle of their worldview.

Liberals have had remarkable historical success is glossing over the internal contradictions of their ideas – such as the contradictions that Rousseau never bothered to explain. Liberals achieved this conceptual tour de force with their romantic belief in the inevitability of progress leading to a future utopia and their sentimental belief in the innate goodness of man. As a result of this romantic triumph of feelings over reason, the various strands of liberalism held together for two centuries.

Interestingly, liberalism coalesced as the political branch of the Romantic movement. Liberalism retained its romantic appeal as late as the presidency of John F. Kennedy. In 1969, art historian Kenneth Clark said that "we are the nearly bankrupt heirs" of the Romantic movement. At that time, the liberal worldview was already in crisis. Liberalism might not survive the death of the Romantic movement.

Interestingly, liberalism coalesced as the political branch of the Romantic movement. Liberalism retained its romantic appeal as late as the presidency of John F. Kennedy. In 1969, art historian Kenneth Clark said that "we are the nearly bankrupt heirs" of the Romantic movement. At that time, the liberal worldview was already in crisis. Liberalism might not survive the death of the Romantic movement.The liberal worldview has been unraveling in Europe since 1920 and in America since 1968-70. In contrast, the five camps of conservatives still adhere to the presuppositions of their worldview. Their faithful adherence to first principles gives them a logical consistency and coherence that liberalism no longer has. This is the conservative advantage.

The religious implications of liberalism

The liberal worldview consists of four quasi-religious presuppositions: 1) the belief in the inherent goodness of man, 2) the belief that society is the source of human evil, 3) the belief in the inevitability of progress toward a future utopia, and 4) the belief that government can play a redemptive and messianic role for mankind.

These four quasi-religious beliefs contradict the teachings of doctrinally orthodox Christianity. Some theologians classify these beliefs as heresies because they eliminate the need of sinners for a divine savior. Liberals have adhered to the four heresies for two centuries with a quasi-religious faith. For some liberals, the quasi-religion of liberal humanism is a substitute for Christianity. That is why liberal idealism has had a messianic tone. Other liberals have grafted the four heresies into some branches of Christianity and produced the pseudo-religion of liberal Protestantism.

Religious experimentation

During the French Revolution (1779-1799), Christianity was suppressed and various experiments were made in developing substitute religions. For example, the Cathedral of Notre Dame was used to celebrate a religion of reason and nature under the aegis of pagan gods. During the reign of terror, Robespierre established a state religion of Deism.

In 1799, Napoleon decided that the newly-invented religions of liberalism were failures. He re-established Christianity not because he was a believer, but because he saw Christianity as indispensable to the stability of the realm. The common people, exhausted by revolution and weird religious and political experiments, gratefully flooded back into the churches.

In England, liberals realized that they could not stop Christianity, so they concentrated on subverting it with liberalism and using Christian institutions to propagate liberal ideas. As a result of the partial success and partial failure of this agenda, a spectrum of theology exists in the churches in England and America ranging from liberal to conservative.

Parallels of theology and politics

Parallels of theology and politicsIt is no accident that the majority of church-going theological liberals are also political liberals, and the majority of church-going theological conservatives are also political conservatives. After all, theology plays a part in developing the first principles of worldviews, and worldviews lie at the root of political philosophy.

It is no accident that the historical rise of doctrinally conservative Christian denominations and sects roughly corresponds with the rise of political conservatism in America (1950-2000). It is also no accident that the decline of liberal Protestantism (1965-2000) roughly corresponds with the time of crisis in the liberal worldview (1968-2000).

The lobotomy of liberalism

Postmodern liberals have cut themselves off from the four core beliefs of the liberal worldview. As a result, liberalism is psychologically and intellectually disintegrating. The intellectual disintegration of liberalism is evidenced by 1) group think, 2) the inability to formulate a logical argument or develop a positive program, 3) the rise of left-wing conspiracy theories, 4) the use of indoctrination techniques in schools, 5) the demonization of opponents, 6) the shouting down of opponents, and 7) paranoid obsessions with catastrophe, such as the post-nuclear Armageddon fantasies of Hollywood and the faddish warnings of environmental catastrophe of junk science.

A person who is watching the collapse of his worldview thinks the fabric of the world is coming apart at the seams – and tends to have illusions of impending catastrophes. This blinds him to real dangers. If one is obsessed with global warming hype, for example, he will not take seriously the real threat of Muslim terrorism.

The disappearance of reason

Why cannot liberals think logically anymore? Did the lobotomy of liberalism cut them off from reason?

All logic must begin with presuppositions or first principles. Postmodern liberals have thrown away the presuppositions of their worldview. In a prior essay, I identified the three common approaches to thinking that reject the use of presuppositions. My thesis was that all of these substitute approaches must, of necessity, lead to logical fallacies.

Descent into nihilism

Leo Strauss (1899-1973), the father of neo-conservatism, predicted that liberalism must eventually give way to relativism and that relativism must eventually give way to nihilism. Nihilism is the final stage of negation after all the strands of a political philosophy have been peeled away.

Leo Strauss (1899-1973), the father of neo-conservatism, predicted that liberalism must eventually give way to relativism and that relativism must eventually give way to nihilism. Nihilism is the final stage of negation after all the strands of a political philosophy have been peeled away.As one moves left through the spectrum of beliefs in the Democratic party, one will find relativism just to the left of center. The next step to the left on the liberal rainbow is skepticism. Cynicism follows skepticism, and nihilism follows cynicism. Michael Moore, who produces dishonest anti-American propaganda, is a blackguard of cynicism. To the left of Moore, one finds the fiends of nihilism. The land of intellectual nihilism is reserved for haters, slanderers, conspiracy theorists, and embittered and hysterical fools like Cindy Sheehan and the bloggers of Moveon.org. Interestingly, the malice and paranoia of Sheehan is reminiscent of Rousseau, the father of liberalism.

The Christopher Hitchens phenomenon

Christopher Hitchens was once an important voice of the far left, but is now disillusioned with the left. He remains an atheist and retains some of his roots in Enlightenment and Marxist thought. In practice, he seems to be an occasional neo-con fellow traveler. He does not embrace anything like a conservative worldview, but he finds that on the whole, conservative thought is more rational, more coherent, and less self-contradictory than the woozy world of left-think.

Having fled the intellectually sinking ship of liberalism, Hitchens has found temporary refuge on board U.S.S. Conservatism. He is seasick, hates the food, and has sardonic words of contempt for passengers and crew, but he knows the ship is seaworthy. He can survive upon the alien ship of conservatism and live a life banished at sea, until he can find land congenial for his foot to step on.

Hitchens amuses himself by ridiculing the stout crew of U.S.S. Conservatism and waxing poetic about the fatal irony of his unhappy voyage. He has been floated on foreign waters surrounded by uncongenial company for some fifteen years, finding consolation in the fiery missiles he sends out against a liberalism gone mad. He is deeply embittered that his natural home of liberalism is no longer fit for a sane man to live in.

The wrecked ship of liberalism has many refugees floating upon the flotsam and jetsam of the intellectual seas. What is it about Hitchens that makes him interesting? His intellectual wits have noticeably sharpened since he has been lost at sea, floating on a ship built upon presuppositions that he rejects. Hitchens has become intellectually interesting in ways he was not when he strutted upon the proud land of left-world.

Worldviews and the Hitchens syndrome

How are we to understand the phenomenon of Hitchens sharpening his wits in intellectual exile? It holds a key to understanding why the rising intellectual powers of the conservative movement have swamped the intellectually bankrupt thought of the left.

Man cannot function without worldviews, but some aging worldviews have a tendency toward gradual constriction until there is not enough room for the mind to maneuver. The Christian worldview resisted this tendency to the extent that it left a space for a transcendent realm that is outside this world.

Man cannot function without worldviews, but some aging worldviews have a tendency toward gradual constriction until there is not enough room for the mind to maneuver. The Christian worldview resisted this tendency to the extent that it left a space for a transcendent realm that is outside this world.When a collapsing worldview begins to resemble a closed system, the human mind shuts down. Reason cannot exist within a closed system. However, if one briefly steps out of his constricted worldview and visits another, the mind is momentarily rejuvenated. That is why Hitchen's voyage on U.S.S. Conservatism revived his rational faculties.

Hitchens and Jennings

Just before the first Persian Gulf war (1990-91), Christopher Hitchens and the late Peter Jennings of ABC News were traveling together towards Kuwait. Hitchens said that the measure of success would now be, not the recovery of Kuwait, but the replacement of the Baathist order. Hitchens said, "I shall never forget his response which was journalist to journalist, 'That is only if we say so.'" (Source: Theater of War, a book review by Hitchens in the Claremont Review of Books, Winter, 2006-7)

Jennings thought the public conception of the Iraq war would be determined by leading liberal journalists. He effectively said, "People will think what our clique tells them to think." Journalism had been replaced by indoctrination by a small elite clique.

Hitchens had to either check his intellect at the door and join the group-think clique who sought to indoctrinate the public, or flee the land of the liberals.

Conservatism and the Hitchens syndome

The noticeable sharpening of Hitchen's wits points us to another conservative intellectual advantage. Every conservative intellectual has debated with conservatives of other camps. When I was in college, traditionalists were constantly debating libertarians. Now, the Christian conservatives are debating the neo-cons.

These constant internecine debates have sharpened the wits of every conservative thinker. I like to call it the "Hitchens syndrome." The intellectual edge gives conservatives special advantages in exposing the decaying worldview of liberals.

Debates with liberals have forced conservatives to constantly think about first principles. The worldview of liberalism is so different from the worldview of conservatism that it is extremely difficult to come to agreement, or even understand what the other person is saying. Sometimes the only way forward in such a situation is to return to conservative first principles and critique liberal first principles. Through such exercises, liberals have unwittingly helped conservatives cling tightly to their first principles, while they themselves were losing their grip on their own first principles.

A time of upheaval

A time of upheavalWhen a person changes his worldview, he goes through a time of personal upheaval like Rousseau and Christopher Hitchens. All his ideas, his interpretations of events, and agendas must be revisited, deconstructed, and reconstructed. All settled ground has collapsed, and new footholds must be sought.

When a society changes its dominant worldview, that society must go through a time of upheaval. As conservatism replaces liberalism as the dominant worldview of the society, many people will be confused and alienated. The rage and paranoia of the left are an important indicator that we are entering a time of trouble. As Bette Davis said in the movie All About Eve, "Fasten your seat belts. It is going to be a bumpy ride."

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmericaI first became acquainted with Fred Hutchison in December 2003, when he contacted me about an article he was interested in writing for RenewAmerica about Alan Keyes. From that auspicious moment until God took him a little more than six years later, we published over 200 of Fred's incomparable essays — usually on some vital aspect of the modern "culture war," written with wit and disarming logic from Fred's brilliant perspective of history, philosophy, science, and scripture.

It was obvious to me from the beginning that Fred was in a class by himself among American conservative writers, and I was honored to feature his insights at RA.

I greatly miss Fred, who died of a brain tumor on August 10, 2010. What a gentle — yet profoundly powerful — voice of reason and godly truth! I'm delighted to see his remarkable essays on the history of conservatism brought together in a masterfully-edited volume by Julie Klusty. Restoring History is a wonderful tribute to a truly great man.

The book is available at Amazon.com.

The views expressed by RenewAmerica analysts generally reflect the VALUES AND PHILOSOPHY of RenewAmerica — although each writer is responsible for the accuracy of individual pieces, and the position taken is the writer's own.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)