Renew America and America's founding

Fred Hutchison, RenewAmerica analyst

Renew America, now recognized by About.com as one of the top ten conservative web sites in the U.S., stands out as being the most Christian of the ten and the site most concerned with issues pertaining to America's founding.

Renew America, now recognized by About.com as one of the top ten conservative web sites in the U.S., stands out as being the most Christian of the ten and the site most concerned with issues pertaining to America's founding.

The last time I saw Alan Keyes, he said to me that he had spent his entire life studying the Constitution and America's founding. Keyes is no longer affiliated with Renew America. He has gone the third party route, and many of us here prefer to avoid that one-way ticket to political irrelevance. However, we don't want to stop being a special web site about America's founding.

There is no replacing Keyes' massive knowledge base, but it occurred to me that my study of the five historic kinds of conservatism might help to inform us about the Constitution.

Does the Constitution embody conservative principles?

Some conservatives embrace the Constitution as though it were the source and ground of their conservative principles. This is remarkable, because the Constitution does not adumbrate a political philosophy. It establishes a legal foundation for the nation and the jurisdictions of the branches and functions of government.

In contrast, the Federalist Papers, which were written to persuade the various states to adopt the Constitution, is filled with principles of political philosophy. The document was compiled from newspaper essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. Madison was especially qualified to write the Federalist Papers because he was the principal author of the Constitution.

I propose to look for the five historic kinds of conservatism in the Federalist Papers to find out whether or not the Constitution is a document shaped according to conservative principles. When the Federalist Papers were written, the American states were formally connected with one another via The Articles of Confederation. Changing from a confederacy to a federal union was a revolutionary step, and conservatives don't like revolutions. Therefore, for a conservative to approve of such a revolution, the new Constitution had better conform to conservative principles.

I propose to look for the five historic kinds of conservatism in the Federalist Papers to find out whether or not the Constitution is a document shaped according to conservative principles. When the Federalist Papers were written, the American states were formally connected with one another via The Articles of Confederation. Changing from a confederacy to a federal union was a revolutionary step, and conservatives don't like revolutions. Therefore, for a conservative to approve of such a revolution, the new Constitution had better conform to conservative principles.

The Federalist Papers correspond in length to a large book, so this project will have to be undertaken for Renew America in a series of stages, possibly alternating with other essays. This review includes the first 14 essays published by the three founders concerning "the importance of the union." I shall skip essays #15–22, which pertain to problems with the Articles of Confederation. On another day, I hope to consider essays #23–36, which are "arguments for the kind of government contained in the Constitution." There are 85 essays in total, including a number of essays assigned to each of the three branches of government.

Federalist #1 by Alexander Hamilton — Grand introduction

In this first essay, Hamilton comes across as a practical thinker, emphasizing the inadequacy of the Articles of Confederation. However, he is acutely aware that men are not angels and are often rascals. As such, he seems to borrow from Christian conservatism the concept of the fall of man. However, Hamilton later explains that he got his pessimistic view of man from reading history. Therefore, I take him to be a traditionalist conservative.

Hamilton warns of two kinds of proud and selfish men who might resist the new Constitution:

1. Those who seek self-aggrandizement in their power and personal interests. The Constitution is a masterpiece of limiting and balancing power so that no ambitious man can get too much power in his hands — lest he turn out to be a rascal and a tyrant. We shall discover that the Constitution is expressly designed to prevent ambitious men from getting too much power and thereby becoming tyrants.

2. Those who oppose ratification of the Constitution because they are protecting their present powers, offices, and financial interests. This statement gives the lie to the left-wing historians who make out that the Constitution was established to protect social class privileges and interests. We learn here that self-seeking men of high social class, wealth, and prominence often opposed the new Constitution.

Hamilton published the Federalist Papers in the New York newspapers because New York had a lot of rich, influential men who opposed the ratification of the Constitution. Hamilton was the ringleader of Federalist Papers project. Hamilton, therefore, ought to be remembered as a founding father of first rank.

Hamilton published the Federalist Papers in the New York newspapers because New York had a lot of rich, influential men who opposed the ratification of the Constitution. Hamilton was the ringleader of Federalist Papers project. Hamilton, therefore, ought to be remembered as a founding father of first rank.

Why would rich, powerful men oppose the Constitution? Because the Articles of Confederation did not have sufficient protections against powerful men getting too much power. They might have gained power under the Articles of Confederation that they could not retain under the Constitution.

Here we get a glimpse of the Constitution protecting the freedom of the ordinary person against the government when powerful, wealthy, and selfish persons grasp the levers of power. This is a libertarian conservative principle.

Federalist #2 by John Jay

Jay says people must cede certain of their natural rights in order to furnish the government with power. The pregnant implication is that as the power of the government grows, the rights of the individual shrinks. This idea is a surprisingly modern version of libertarian conservative thought. Jay's phrase "natural rights" reveals a strain of natural law conservatism.

Jay's libertarian natural law tendency contradicts an older Christian view of natural law, to wit: Government is ordained by God and is therefore a good institution, not a "necessary evil" as the libertarians think. As long as government performs its appropriate functions and remains within its natural sphere as ordained by Providence, its powers do not represent a diminution of the natural rights of individuals. However, if a ruler wickedly steps over the natural boundaries of his jurisdiction or does things that are not appropriate for government to do, the ruler becomes a tyrant and denies the citizens some of their natural rights. The founders were not on a mission to bring government to an irreducible minimum, but to correctly define the role of government and confine government to that role. In this, they generally leaned more towards the Christian perspective of natural law than to libertarianism.

Jay argues that the American states must be united to become one nation because of the common manners, customs, culture, religion, and language of the people of the original 13 states. Here, traditionalist conservatism makes a strong appearance in this document. Jay emphasizes that the people have a strong attachment to both union and liberty. The Anglo-Saxon people of England and America had a genius for balancing freedom and order. Here we see that they are also good at balancing union and liberty.

Jay argues that the American states must be united to become one nation because of the common manners, customs, culture, religion, and language of the people of the original 13 states. Here, traditionalist conservatism makes a strong appearance in this document. Jay emphasizes that the people have a strong attachment to both union and liberty. The Anglo-Saxon people of England and America had a genius for balancing freedom and order. Here we see that they are also good at balancing union and liberty.

Jay hopes that wise and experienced men from all parts of the union will sit in Congress. These should be tried and tested for patriotism and abilities — particularly among those who have grown old in acquiring political information and whose merits and virtues are proven through long service. These kernels of traditionalist wisdom are a rebuke to the hasty elevation of a young, inexperienced, untested office-holder such as Barack Obama.

Federalist #3-5 by John Jay — Foreign force and ignorance

To the gratification of neoconservatives and the dismay of libertarians, Jay puts safety in first place and not liberty. Traditionists and natural law conservatives prefer to strike a balance between safety and liberty. The founding fathers cared about liberty, but did not design the Constitution to maximize liberty. However, they added the Bill of Rights as amendments to the Constitution in order to add further protections to liberty.

In Federalist #3-5, Jay is primarily interested in safety from foreign powers, but also mentions internal safety. He offers a variety of reasons why America is safer in a federal union — not just in war but in its ability to formulate a more coherent foreign policy and navigate the tricky grounds of foreign policy. Here we discover a deep distrust of the rivalries, games, and treachery of European nations. Here again is a hint of neoconservatism. These sentiments are the exact opposite of the modern utopian confidence in internationalism and in world government.

In #5, Jay says a federal union is the best form of government to secure religion, liberty, and material prosperity. Here we will get applause from Christian conservatives, natural law conservatives, and libertarians.

Federalist #6-9 by Hamilton

Hamilton tells us that the accumulated experience of history teaches that men are "ambitious, vindictive, and rapacious." They lust for power, desire preeminence, and domination, and are jealous of power. What the traditionalist Hamilton learned about this from history and experience is in accord with what Christianity teaches about the wickedness of fallen man.

Hamilton, a student of history and the classics, tells how Pericles, the great leader of Athens during her golden age, brought ruin to foreign principalities out of private pique and, in one case, due to the resentment of a prostitute. Men are rotten even in a golden age. Hamilton also offers the example of Cardinal Wolsey, who plunged England into war with France — contrary to England's interests — in order to gratify Charles V, hoping that Charles would help him become the next pope.

Hamilton, a student of history and the classics, tells how Pericles, the great leader of Athens during her golden age, brought ruin to foreign principalities out of private pique and, in one case, due to the resentment of a prostitute. Men are rotten even in a golden age. Hamilton also offers the example of Cardinal Wolsey, who plunged England into war with France — contrary to England's interests — in order to gratify Charles V, hoping that Charles would help him become the next pope.

As though he was caught up in a great enthusiasm, Hamilton tells story after story from the history books about the depravity of man. Perhaps he felt that if his readers learned nothing else, they must understand that men are too wicked to be trusted — and therefore must have a form of government that keeps wicked men from getting too much power and that keeps arbitrary power out of their hands.

Because of these unpleasant human traits, Hamilton is worried that the states will quarrel with each other and sometimes fight each other. There will be more protection from these internecine tumults in a union of states than in a confederacy. Here Hamilton seems to prophesy the southern confederacy and the civil war. But Hamilton is not a prophet. He understands human nature.

He expresses contempt of "Utopian speculation" that we can expect sovereign states to live indefinitely in peace side by side. Even in his day, the progressives were indulging their naive hopes about world peace. Our wise founders like Hamilton had contempt for these foolish early progressives.

According to Hamilton, the genius of republics is that they are pacific. The spirit of commerce softens their manners and gives them a dislike of ruinous wars. As states in a union trade with each other, they desire amity with each other so that trade may flourish. Here, Hamilton hints that a union is a republic and a confederation is not. Hamilton is truly the father of the Federalist Party and its heir, the Republican Party. Hamilton would have us remember that America is primarily a republic, and only secondarily a democracy. Hamilton's wisdom on these matters is pure traditionalist conservatism.

Essay #7 involves a consideration of the many factors that could cause states that are not united in union to fight one another. In essay #8, he says that a war between the states would cause much greater distress than any other kind of war. Of course, the devastation, horror, and distress of the American Civil War was far worse than even our pessimistic Mr. Hamilton could expect. How did Hamilton get so wise? As a learned traditionalist, he says that he does not trust theory about man, but trusts the harsh lessons about man that he reads in the history books.

Essay #7 involves a consideration of the many factors that could cause states that are not united in union to fight one another. In essay #8, he says that a war between the states would cause much greater distress than any other kind of war. Of course, the devastation, horror, and distress of the American Civil War was far worse than even our pessimistic Mr. Hamilton could expect. How did Hamilton get so wise? As a learned traditionalist, he says that he does not trust theory about man, but trusts the harsh lessons about man that he reads in the history books.

In essay #8, Hamilton voices his fear of standing armies, which he hopes America will not need because she is protected from European armies by the Atlantic Ocean. However, in contrast to standing armies, Hamilton does see the need for state militias composed of citizen soldiers in contradistinction to the professional soldiers in a professional army.

In essay #9, Hamilton explains why the union of states is a good protection against a civil war of states. History shows that those who most celebrated the idea of the union were most opposed to sectional division and secession.

After describing the despotic enemies of liberty who fought against the Italian republics, Hamilton makes a statement that agrees with my account of conservatism as an ancient sentiment among men. "Stupendous fabrics [I suppose this a reference to Edmund Burke's 'social fabric,' a key idea in traditionalist conservatism] reared on the basis of liberty, which have flourished through the ages [yes libertarians, the love of liberty is ancient] have in a few glorious instances refuted their gloomy sophisms [that is to say, have refuted the false arguments of despots who oppose liberty]." Hamilton goes on to say that he anticipates that America would continue weaving the fabric of liberty and refuting the sophists of despotism.

Hamilton points to advances in political science that are useful to the preservation of freedom. Thus, for the first time, the Federalist Papers mention checks and balances, and departmentalization. Although Hamilton does not yet mention separation of powers, or bicameral legislatures, we can asume that these are included in his ideas of "advances in political science."

As a student of Montesquieu, Hamilton found it necessary to defend the Constitution against his claim that republics are more likely to flourish when they are small principalities. Hamilton argues that the various American states have these advantages while gaining other advantages from the federal union.

#10 James Madison — Factions and property rights

#10 James Madison — Factions and property rights

Madison speaks at great length of the danger of factions and disorders and the remedy to be found in the union. These are problems that pure democracies cannot solve.

Madison is the first to speak of property rights. "Property rights originate from the diverse faculties of men." This idea comes from John Locke's Natural Law principle that as man adds his labor to the provisions of nature, they become his in such a way that no man can feel himself defrauded by not possessing that property. Madison says that one of the purposes of government is to protect "these faculties" and also to protect this property. The fifth amendment to the Constitution holds that no man shall be denied of life, liberty, and property without due course of law. The protection of property is especially important to libertarians and traditionalists.

When there is freedom, there will be different and equal faculties for having property and different individual possessions of property. The government must protect these differences even though they are a cause of faction. Already Madison was anticipating a future party that organizes the haves and a party that organizes the have-nots.

Madison sees some remedy for faction in representative federal legislatures and by farming local and detailed matters to state legislatures and matters of more general scope to Congress.

#11–13 Hamilton — Commerce and a navy, economics

An extensive consideration of federal policy is followed by an appeal that the nation should have a navy to protect commerce and freedom of the seas. This section would appeal to neoconservatives. Hamilton notes that a union is conducive to commerce and the collection of taxes. He warns that the wrong taxation policy may be injurious to commerce. Hamilton proposes import duties of 3% and a shilling per gallon of rum. These light taxes sound like supply-side economics.

He looks disapprovingly at the regulation of commerce in France. Whether Hamilton had read The Wealth of Nations (1776) by Adam Smith is not clear, but Madison, a classical liberal, probably had read it. It should give libertarians a surge of joy to know that some of the founding fathers believed in free enterprise and opposed government regulation of business.

#14 Madison — The size of the republic, and the geography of the states

The patriotic sentiments of the Revolution live on in the heart of Madison. He says, "Blood shed in defense of our sacred rights consecrates the union as one people." This religious-patriotic view of the indissolubility of the union would last until the civil war. Traditionists are particularly likely to adopt this view. It is revealing that Madison refers to our rights as "sacred," instead of calling them "natural." He apparently prefers the Christian view of natural law.

The patriotic sentiments of the Revolution live on in the heart of Madison. He says, "Blood shed in defense of our sacred rights consecrates the union as one people." This religious-patriotic view of the indissolubility of the union would last until the civil war. Traditionists are particularly likely to adopt this view. It is revealing that Madison refers to our rights as "sacred," instead of calling them "natural." He apparently prefers the Christian view of natural law.

This concludes my review of essays #1- 14, "The Importance of the Union." All five kinds of conservatism make an appearance in these essays. The U.S. Constitution should be dear in the hearts of conservatives.

I shall skip essays #15–22, "Defects in the Articles of Confederation."

On another day, I hope to review #23–36, "Arguments for the type of government contained in the Constitution." 49 additional sections were published in other sections, and I hope to select some of these for review.

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

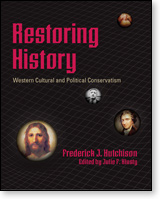

I first became acquainted with Fred Hutchison in December 2003, when he contacted me about an article he was interested in writing for RenewAmerica about Alan Keyes. From that auspicious moment until God took him a little more than six years later, we published over 200 of Fred's incomparable essays — usually on some vital aspect of the modern "culture war," written with wit and disarming logic from Fred's brilliant perspective of history, philosophy, science, and scripture.

It was obvious to me from the beginning that Fred was in a class by himself among American conservative writers, and I was honored to feature his insights at RA.

I greatly miss Fred, who died of a brain tumor on August 10, 2010. What a gentle — yet profoundly powerful — voice of reason and godly truth! I'm delighted to see his remarkable essays on the history of conservatism brought together in a masterfully-edited volume by Julie Klusty. Restoring History is a wonderful tribute to a truly great man.

The book is available at Amazon.com.

© Fred Hutchison

August 27, 2009

Renew America, now recognized by About.com as one of the top ten conservative web sites in the U.S., stands out as being the most Christian of the ten and the site most concerned with issues pertaining to America's founding.

Renew America, now recognized by About.com as one of the top ten conservative web sites in the U.S., stands out as being the most Christian of the ten and the site most concerned with issues pertaining to America's founding.The last time I saw Alan Keyes, he said to me that he had spent his entire life studying the Constitution and America's founding. Keyes is no longer affiliated with Renew America. He has gone the third party route, and many of us here prefer to avoid that one-way ticket to political irrelevance. However, we don't want to stop being a special web site about America's founding.

There is no replacing Keyes' massive knowledge base, but it occurred to me that my study of the five historic kinds of conservatism might help to inform us about the Constitution.

Does the Constitution embody conservative principles?

Some conservatives embrace the Constitution as though it were the source and ground of their conservative principles. This is remarkable, because the Constitution does not adumbrate a political philosophy. It establishes a legal foundation for the nation and the jurisdictions of the branches and functions of government.

In contrast, the Federalist Papers, which were written to persuade the various states to adopt the Constitution, is filled with principles of political philosophy. The document was compiled from newspaper essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. Madison was especially qualified to write the Federalist Papers because he was the principal author of the Constitution.

I propose to look for the five historic kinds of conservatism in the Federalist Papers to find out whether or not the Constitution is a document shaped according to conservative principles. When the Federalist Papers were written, the American states were formally connected with one another via The Articles of Confederation. Changing from a confederacy to a federal union was a revolutionary step, and conservatives don't like revolutions. Therefore, for a conservative to approve of such a revolution, the new Constitution had better conform to conservative principles.

I propose to look for the five historic kinds of conservatism in the Federalist Papers to find out whether or not the Constitution is a document shaped according to conservative principles. When the Federalist Papers were written, the American states were formally connected with one another via The Articles of Confederation. Changing from a confederacy to a federal union was a revolutionary step, and conservatives don't like revolutions. Therefore, for a conservative to approve of such a revolution, the new Constitution had better conform to conservative principles.The Federalist Papers correspond in length to a large book, so this project will have to be undertaken for Renew America in a series of stages, possibly alternating with other essays. This review includes the first 14 essays published by the three founders concerning "the importance of the union." I shall skip essays #15–22, which pertain to problems with the Articles of Confederation. On another day, I hope to consider essays #23–36, which are "arguments for the kind of government contained in the Constitution." There are 85 essays in total, including a number of essays assigned to each of the three branches of government.

Federalist #1 by Alexander Hamilton — Grand introduction

In this first essay, Hamilton comes across as a practical thinker, emphasizing the inadequacy of the Articles of Confederation. However, he is acutely aware that men are not angels and are often rascals. As such, he seems to borrow from Christian conservatism the concept of the fall of man. However, Hamilton later explains that he got his pessimistic view of man from reading history. Therefore, I take him to be a traditionalist conservative.

Hamilton warns of two kinds of proud and selfish men who might resist the new Constitution:

1. Those who seek self-aggrandizement in their power and personal interests. The Constitution is a masterpiece of limiting and balancing power so that no ambitious man can get too much power in his hands — lest he turn out to be a rascal and a tyrant. We shall discover that the Constitution is expressly designed to prevent ambitious men from getting too much power and thereby becoming tyrants.

2. Those who oppose ratification of the Constitution because they are protecting their present powers, offices, and financial interests. This statement gives the lie to the left-wing historians who make out that the Constitution was established to protect social class privileges and interests. We learn here that self-seeking men of high social class, wealth, and prominence often opposed the new Constitution.

Hamilton published the Federalist Papers in the New York newspapers because New York had a lot of rich, influential men who opposed the ratification of the Constitution. Hamilton was the ringleader of Federalist Papers project. Hamilton, therefore, ought to be remembered as a founding father of first rank.

Hamilton published the Federalist Papers in the New York newspapers because New York had a lot of rich, influential men who opposed the ratification of the Constitution. Hamilton was the ringleader of Federalist Papers project. Hamilton, therefore, ought to be remembered as a founding father of first rank.Why would rich, powerful men oppose the Constitution? Because the Articles of Confederation did not have sufficient protections against powerful men getting too much power. They might have gained power under the Articles of Confederation that they could not retain under the Constitution.

Here we get a glimpse of the Constitution protecting the freedom of the ordinary person against the government when powerful, wealthy, and selfish persons grasp the levers of power. This is a libertarian conservative principle.

Federalist #2 by John Jay

Jay says people must cede certain of their natural rights in order to furnish the government with power. The pregnant implication is that as the power of the government grows, the rights of the individual shrinks. This idea is a surprisingly modern version of libertarian conservative thought. Jay's phrase "natural rights" reveals a strain of natural law conservatism.

Jay's libertarian natural law tendency contradicts an older Christian view of natural law, to wit: Government is ordained by God and is therefore a good institution, not a "necessary evil" as the libertarians think. As long as government performs its appropriate functions and remains within its natural sphere as ordained by Providence, its powers do not represent a diminution of the natural rights of individuals. However, if a ruler wickedly steps over the natural boundaries of his jurisdiction or does things that are not appropriate for government to do, the ruler becomes a tyrant and denies the citizens some of their natural rights. The founders were not on a mission to bring government to an irreducible minimum, but to correctly define the role of government and confine government to that role. In this, they generally leaned more towards the Christian perspective of natural law than to libertarianism.

Jay argues that the American states must be united to become one nation because of the common manners, customs, culture, religion, and language of the people of the original 13 states. Here, traditionalist conservatism makes a strong appearance in this document. Jay emphasizes that the people have a strong attachment to both union and liberty. The Anglo-Saxon people of England and America had a genius for balancing freedom and order. Here we see that they are also good at balancing union and liberty.

Jay argues that the American states must be united to become one nation because of the common manners, customs, culture, religion, and language of the people of the original 13 states. Here, traditionalist conservatism makes a strong appearance in this document. Jay emphasizes that the people have a strong attachment to both union and liberty. The Anglo-Saxon people of England and America had a genius for balancing freedom and order. Here we see that they are also good at balancing union and liberty.Jay hopes that wise and experienced men from all parts of the union will sit in Congress. These should be tried and tested for patriotism and abilities — particularly among those who have grown old in acquiring political information and whose merits and virtues are proven through long service. These kernels of traditionalist wisdom are a rebuke to the hasty elevation of a young, inexperienced, untested office-holder such as Barack Obama.

Federalist #3-5 by John Jay — Foreign force and ignorance

To the gratification of neoconservatives and the dismay of libertarians, Jay puts safety in first place and not liberty. Traditionists and natural law conservatives prefer to strike a balance between safety and liberty. The founding fathers cared about liberty, but did not design the Constitution to maximize liberty. However, they added the Bill of Rights as amendments to the Constitution in order to add further protections to liberty.

In Federalist #3-5, Jay is primarily interested in safety from foreign powers, but also mentions internal safety. He offers a variety of reasons why America is safer in a federal union — not just in war but in its ability to formulate a more coherent foreign policy and navigate the tricky grounds of foreign policy. Here we discover a deep distrust of the rivalries, games, and treachery of European nations. Here again is a hint of neoconservatism. These sentiments are the exact opposite of the modern utopian confidence in internationalism and in world government.

In #5, Jay says a federal union is the best form of government to secure religion, liberty, and material prosperity. Here we will get applause from Christian conservatives, natural law conservatives, and libertarians.

Federalist #6-9 by Hamilton

Hamilton tells us that the accumulated experience of history teaches that men are "ambitious, vindictive, and rapacious." They lust for power, desire preeminence, and domination, and are jealous of power. What the traditionalist Hamilton learned about this from history and experience is in accord with what Christianity teaches about the wickedness of fallen man.

Hamilton, a student of history and the classics, tells how Pericles, the great leader of Athens during her golden age, brought ruin to foreign principalities out of private pique and, in one case, due to the resentment of a prostitute. Men are rotten even in a golden age. Hamilton also offers the example of Cardinal Wolsey, who plunged England into war with France — contrary to England's interests — in order to gratify Charles V, hoping that Charles would help him become the next pope.

Hamilton, a student of history and the classics, tells how Pericles, the great leader of Athens during her golden age, brought ruin to foreign principalities out of private pique and, in one case, due to the resentment of a prostitute. Men are rotten even in a golden age. Hamilton also offers the example of Cardinal Wolsey, who plunged England into war with France — contrary to England's interests — in order to gratify Charles V, hoping that Charles would help him become the next pope.As though he was caught up in a great enthusiasm, Hamilton tells story after story from the history books about the depravity of man. Perhaps he felt that if his readers learned nothing else, they must understand that men are too wicked to be trusted — and therefore must have a form of government that keeps wicked men from getting too much power and that keeps arbitrary power out of their hands.

Because of these unpleasant human traits, Hamilton is worried that the states will quarrel with each other and sometimes fight each other. There will be more protection from these internecine tumults in a union of states than in a confederacy. Here Hamilton seems to prophesy the southern confederacy and the civil war. But Hamilton is not a prophet. He understands human nature.

He expresses contempt of "Utopian speculation" that we can expect sovereign states to live indefinitely in peace side by side. Even in his day, the progressives were indulging their naive hopes about world peace. Our wise founders like Hamilton had contempt for these foolish early progressives.

According to Hamilton, the genius of republics is that they are pacific. The spirit of commerce softens their manners and gives them a dislike of ruinous wars. As states in a union trade with each other, they desire amity with each other so that trade may flourish. Here, Hamilton hints that a union is a republic and a confederation is not. Hamilton is truly the father of the Federalist Party and its heir, the Republican Party. Hamilton would have us remember that America is primarily a republic, and only secondarily a democracy. Hamilton's wisdom on these matters is pure traditionalist conservatism.

Essay #7 involves a consideration of the many factors that could cause states that are not united in union to fight one another. In essay #8, he says that a war between the states would cause much greater distress than any other kind of war. Of course, the devastation, horror, and distress of the American Civil War was far worse than even our pessimistic Mr. Hamilton could expect. How did Hamilton get so wise? As a learned traditionalist, he says that he does not trust theory about man, but trusts the harsh lessons about man that he reads in the history books.

Essay #7 involves a consideration of the many factors that could cause states that are not united in union to fight one another. In essay #8, he says that a war between the states would cause much greater distress than any other kind of war. Of course, the devastation, horror, and distress of the American Civil War was far worse than even our pessimistic Mr. Hamilton could expect. How did Hamilton get so wise? As a learned traditionalist, he says that he does not trust theory about man, but trusts the harsh lessons about man that he reads in the history books.In essay #8, Hamilton voices his fear of standing armies, which he hopes America will not need because she is protected from European armies by the Atlantic Ocean. However, in contrast to standing armies, Hamilton does see the need for state militias composed of citizen soldiers in contradistinction to the professional soldiers in a professional army.

In essay #9, Hamilton explains why the union of states is a good protection against a civil war of states. History shows that those who most celebrated the idea of the union were most opposed to sectional division and secession.

After describing the despotic enemies of liberty who fought against the Italian republics, Hamilton makes a statement that agrees with my account of conservatism as an ancient sentiment among men. "Stupendous fabrics [I suppose this a reference to Edmund Burke's 'social fabric,' a key idea in traditionalist conservatism] reared on the basis of liberty, which have flourished through the ages [yes libertarians, the love of liberty is ancient] have in a few glorious instances refuted their gloomy sophisms [that is to say, have refuted the false arguments of despots who oppose liberty]." Hamilton goes on to say that he anticipates that America would continue weaving the fabric of liberty and refuting the sophists of despotism.

Hamilton points to advances in political science that are useful to the preservation of freedom. Thus, for the first time, the Federalist Papers mention checks and balances, and departmentalization. Although Hamilton does not yet mention separation of powers, or bicameral legislatures, we can asume that these are included in his ideas of "advances in political science."

As a student of Montesquieu, Hamilton found it necessary to defend the Constitution against his claim that republics are more likely to flourish when they are small principalities. Hamilton argues that the various American states have these advantages while gaining other advantages from the federal union.

#10 James Madison — Factions and property rights

#10 James Madison — Factions and property rightsMadison speaks at great length of the danger of factions and disorders and the remedy to be found in the union. These are problems that pure democracies cannot solve.

Madison is the first to speak of property rights. "Property rights originate from the diverse faculties of men." This idea comes from John Locke's Natural Law principle that as man adds his labor to the provisions of nature, they become his in such a way that no man can feel himself defrauded by not possessing that property. Madison says that one of the purposes of government is to protect "these faculties" and also to protect this property. The fifth amendment to the Constitution holds that no man shall be denied of life, liberty, and property without due course of law. The protection of property is especially important to libertarians and traditionalists.

When there is freedom, there will be different and equal faculties for having property and different individual possessions of property. The government must protect these differences even though they are a cause of faction. Already Madison was anticipating a future party that organizes the haves and a party that organizes the have-nots.

Madison sees some remedy for faction in representative federal legislatures and by farming local and detailed matters to state legislatures and matters of more general scope to Congress.

#11–13 Hamilton — Commerce and a navy, economics

An extensive consideration of federal policy is followed by an appeal that the nation should have a navy to protect commerce and freedom of the seas. This section would appeal to neoconservatives. Hamilton notes that a union is conducive to commerce and the collection of taxes. He warns that the wrong taxation policy may be injurious to commerce. Hamilton proposes import duties of 3% and a shilling per gallon of rum. These light taxes sound like supply-side economics.

He looks disapprovingly at the regulation of commerce in France. Whether Hamilton had read The Wealth of Nations (1776) by Adam Smith is not clear, but Madison, a classical liberal, probably had read it. It should give libertarians a surge of joy to know that some of the founding fathers believed in free enterprise and opposed government regulation of business.

#14 Madison — The size of the republic, and the geography of the states

The patriotic sentiments of the Revolution live on in the heart of Madison. He says, "Blood shed in defense of our sacred rights consecrates the union as one people." This religious-patriotic view of the indissolubility of the union would last until the civil war. Traditionists are particularly likely to adopt this view. It is revealing that Madison refers to our rights as "sacred," instead of calling them "natural." He apparently prefers the Christian view of natural law.

The patriotic sentiments of the Revolution live on in the heart of Madison. He says, "Blood shed in defense of our sacred rights consecrates the union as one people." This religious-patriotic view of the indissolubility of the union would last until the civil war. Traditionists are particularly likely to adopt this view. It is revealing that Madison refers to our rights as "sacred," instead of calling them "natural." He apparently prefers the Christian view of natural law.This concludes my review of essays #1- 14, "The Importance of the Union." All five kinds of conservatism make an appearance in these essays. The U.S. Constitution should be dear in the hearts of conservatives.

I shall skip essays #15–22, "Defects in the Articles of Confederation."

On another day, I hope to review #23–36, "Arguments for the type of government contained in the Constitution." 49 additional sections were published in other sections, and I hope to select some of these for review.

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmericaI first became acquainted with Fred Hutchison in December 2003, when he contacted me about an article he was interested in writing for RenewAmerica about Alan Keyes. From that auspicious moment until God took him a little more than six years later, we published over 200 of Fred's incomparable essays — usually on some vital aspect of the modern "culture war," written with wit and disarming logic from Fred's brilliant perspective of history, philosophy, science, and scripture.

It was obvious to me from the beginning that Fred was in a class by himself among American conservative writers, and I was honored to feature his insights at RA.

I greatly miss Fred, who died of a brain tumor on August 10, 2010. What a gentle — yet profoundly powerful — voice of reason and godly truth! I'm delighted to see his remarkable essays on the history of conservatism brought together in a masterfully-edited volume by Julie Klusty. Restoring History is a wonderful tribute to a truly great man.

The book is available at Amazon.com.

RenewAmerica analyst Fred Hutchison also writes a column for RenewAmerica.

The views expressed by RenewAmerica analysts generally reflect the VALUES AND PHILOSOPHY of RenewAmerica — although each writer is responsible for the accuracy of individual pieces, and the position taken is the writer's own.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)