Wes Vernon

Book review: 'A Man and his Presidents,' by Alvin S. Felzenberg

The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr.

By Wes Vernon

News and entertainment media, to say nothing of the history books, have inundated Americans with their own political versions of our nation's founding and of the political officials and other alert Americans who followed, including our 45 presidents (for whatever the proficiency of their efforts as "keepers of the flame" may have been). By no means, however, are those who made great strides in their contributions to the nation's direction confined to our elected or officially appointed public servants. In fact, some of those "outside the Washington bubble" had an impact that was much more than simply "noteworthy."

Seemingly no end to accomplishments

Seemingly no end to accomplishments

Such a power broker was the late William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925-2008). Unlike some others who quietly dispensed eagerly-received advice to "the power" in the White House Oval Office, Buckley's advice to Barry Goldwater and to Presidents Nixon, Reagan, Bush I, and Bush II was not only by frequent personal contact to the actual "seat of power"; some of it was very public, as in knowing that the political intellectual heavyweights Mr. Buckley was attempting to influence were subscribers to his conservative "must-read" magazine National Review. Actual influence? President George W. Bush summed it up: "Buckley brought conservative thought into the mainstream, and helped lay the intellectual foundation for America's victory in the Cold War."

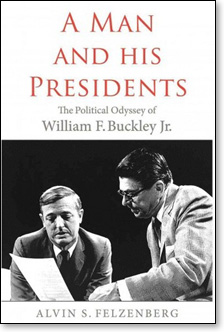

The tribute was fitting, though it arguably left much to be added. That gap is filled admirably by Alvin S. Felzenberg in his new volume A Man and his Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. The author, aside from serving two administrations, is a professor of communications at the University of Pennsylvania and a historian in his own right, as shown, for example, in his 2008 Leaders We Deserved (and a Few We Didn't) – an outstanding and brutally honest rating of our first 42 presidents, excepting William Henry Harrison, whose presidency lasted all of one month.

Mr. Felzenberg also authored Governor Tom Kean: From the New Jersey Statehouse to the 9/11 Commission (2006). The author also served as the primary communications director for that panel. (You may recall having seen Al Felzenberg delivering a briefing to and taking questions from the media during the 9/11 hearings which Governor Kean chaired.)

A longtime attack aimed at America?

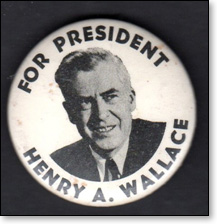

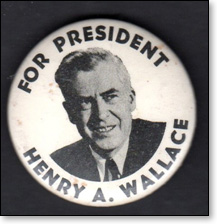

The "third party" presidential campaign of Henry A. Wallace in the 1948 Truman-Dewey contest was a candidacy that a very concerned Bill Buckley took very seriously at the time. Though Wallace ultimately received only 2.4 million popular votes and zero electoral votes, the former vice president (for Roosevelt) did attract a decent-sized intellectual contingent. His Progressive Party had been publicized for its backing and suspected funding by the Communist Party, which was able to gin up demonstrations in New York City. Buckley – a conservative young student, campus politician, and editor – pointed to history to support the point that "ideas advanced during elections could outlast losing campaigns, capture the imagination of intellectuals and under the right circumstances gain acceptance over time."

That might be cited as an example of Buckley's prescience, given the generations-long crawl from the meager vote for Henry Wallace, as the Democrat Party in the following generations seemed to veer

increasingly leftward in small increments until, in 2008, Americans could pull the lever for Barack Obama, who had been mentored by Frank Marshall Davis, an acknowledged Communist. Wallace later

sorrowfully recanted his communist leanings. Obama in his later time bore down on Marxist policies while never acknowledging the arguable origins of the ideas behind them. A more positive and much

shorter example of Buckley's point came when, in 1980, Ronald Reagan told Barry Goldwater that the latter had won his own presidential run in 1964, but "it just took us 16 years to count the votes."

That might be cited as an example of Buckley's prescience, given the generations-long crawl from the meager vote for Henry Wallace, as the Democrat Party in the following generations seemed to veer

increasingly leftward in small increments until, in 2008, Americans could pull the lever for Barack Obama, who had been mentored by Frank Marshall Davis, an acknowledged Communist. Wallace later

sorrowfully recanted his communist leanings. Obama in his later time bore down on Marxist policies while never acknowledging the arguable origins of the ideas behind them. A more positive and much

shorter example of Buckley's point came when, in 1980, Ronald Reagan told Barry Goldwater that the latter had won his own presidential run in 1964, but "it just took us 16 years to count the votes."

True to its principles?

Beyond his very visible years at Yale, Buckley later emerged on the public scene as if he'd been shot out of a cannon. His first of what would be scores of books during the rest of his life was God and Man at Yale. Yale University was a secular institution whose students (in the majority) were nominally Protestant. The school was "conservative," though far more moderate than Buckley, who as a very devout Latin Mass-attending Catholic saw the teaching and the drift of Yale as having gradually taken on a rejection of Christianity and its vital teachings. He viewed Yale as ignoring Christianity, or in some instances, rejecting it. According to the author of A Man and his Presidents, Buckley wanted the university to teach that Christianity was superior to other faiths.

God and Man at Yale was the product of Buckley's own tussles – political and cultural – on the campus of the prestigious Ivy League institution (founded in 1701). This young man, during his student days there, notably was the editor and unabashedly opinionated (but also well-informed) editorial writer for the Yale Daily News. His time as "Chairman" at the paper reflected his stormy political activism as a student and portended what was to be his multiple-controversy-packed career in the decades to come.

What he really thought

Before he walked out the door at Yale, Buckley was selected to deliver the class day oration upon graduation. When those in charge of the event saw Buckley's prepared remarks, they advised him to tone them down before delivery.

Mr. Felzenberg quotes some prepared parts of the text, most of which Buckley insisted on delivering absent "references to specific individuals."

Mr. Felzenberg quotes some prepared parts of the text, most of which Buckley insisted on delivering absent "references to specific individuals."

His comments included: "Here we find men who will tell us Jesus Christ was the greatest fraud that history has known." He said, in some classrooms conventional morality was presented as an anachronism "by human thought." He also urged Yale to proclaim that "collectivism [socialism] was inimical to individual dignity and to the nation's strength and prosperity." (One might add that collectivism, since Buckley's student days, has proven difficult to remove before or after it has done much of its damage (witness decades later the 2017 effort to "repeal and replace" Obamacare. – WV)

What says this senior guru of conservatism?

Both at Yale and later out in the real world, Buckley stirred controversy, and in the give and take of political battle found throughout the many years of his repertoire, Buckley was usually disciplined enough to know where to draw the line without losing the sharp edge he displayed as a masterful debater, at Yale and later on the worldwide political stage. His opponents respected him, and many of them befriended him without either they or he shedding their political convictions. His grip of an issue rarely if ever betrayed him when he was confronted with a debate opponent who was also well briefed of the arguments on both sides... Those were qualities that enabled Bill Buckley to come back week after week for years and face down the next comer on his popular Firing Line TV show. How else would his Firing Line last for 1429 TV episodes until it finally ended? He said he did not wish to "die on the set." (Obviously, he had the intellect and the concentration to multi-task. How else can one whose love of music enabled him the versatility to sit at the piano to play Bach with one hand and "Toot-Toot-Tootsie Good-bye" with the other?)

Then there were the columns in newspapers around the country – usually three per week – and scores of books, as well, while also meeting frequent speech-making demands Of course, the crown jewel of all of William F. Buckley's literary/media efforts is the magazine that started it all – his beloved National Review – "Buckley's magazine" as it was known. That fabled history about "standing athwart" the post-war political New Deal-accepting nation and shouting "Stop" was the turning point for America's post-war days. The magazine remains today on the web.

But there is more

"The Buckley era," best defined as 1945-1982 (starting at Yale) brought conservatism into the mainstream, as President Bush (see above) has said. At that time in history, much of Europe (the half not occupied by Soviet troops), and post-war media and other venues in America, were pushing or going along with a settling down with a collectivism-is-here-to stay attitude. William Buckley was not the only "voice in the wilderness" saying in so many words, hey what is this? Are we still America? Or are we willing to slowly (at first) drift away from the nation of our founders who fought so valiantly to make us an exceptional nation with a Constitution that is the backbone that has made us great?

The limits

The limits

Other conservatives arose, and Buckley welcomed or did not discourage them. But since much of America looked on him as an original steady hand and not a fly-by-night, he took on the job of noting publicly those who in his judgment were doing the cause more harm than good.

Dissenters voiced the Who-do-you-think-you-are retort. Some may have been put off by his transatlantic accent. (Note: Though the Buckleys were thoroughly American, they had some meaningful experiences elsewhere, as for example Bill's two years attending a prep school in England; that may be where he picked up the accent. It was no put-on. That's the way he talked. The woman who would later become his wife Pat, his "best friend," was the daughter of one of the most prominent citizens of Canada.)

Family fights?

Since William Buckley was generally recognized as a foremost post-war leader of conservatives, and was constantly besieged by media inquiring what he thought of this or that other conservative who had made some controversial remark, he felt (rightly or wrongly) that he had to try to draw what he considered the boundaries of what American conservatism was and what it was not.

Buckley publicly drew the lines on basically three or four sources of beyond-the-pale, as he viewed them. These included the "objectivist" group of the late libertarian author Ayn Rand. Their first meeting quickly deteriorated when Rand said to Buckley she could not understand how someone as intelligent as he could possibly believe in God. Her book Atlas Shrugged was roundly slammed in National Review by Whittaker Chambers, the ex-Communist who played a major role is exposing Alger Hiss as a traitor. Secondly, there was the John Birch Society, manly its leadership, which Buckley denounced. Bill Rusher, then a publisher for National Review, told me in the late nineties he had been in on the Buckley discussions of the Birch Society. At the time, he said he objected because well-meaning members of the Society were also fans of National Review. However, Rusher added in retrospect that he believes Buckley was right. And thirdly, the George Wallace segregationists. (Note: Governor Wallace once said to columnist Robert Novak, "You have never heard me call myself a "conservative.") Finally, Buckley ruled out anti-Semites as not deserving any seat at the conservative table.

The McCarthy book

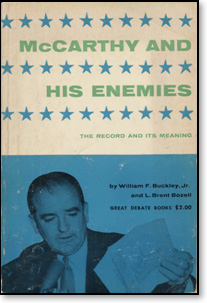

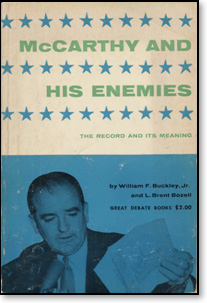

Bill Buckley's second book, co-written with his brother-in-law Brent Bozell, Sr., was McCarthy and his Enemies, a defense of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his battle against Communism. Buckley and Bozell hailed the Wisconsin senator's fight to keep Communists out of government, while acknowledging the senator's lack of required political skills. Basically, they agreed with former leftist – and later National Review writer Max Eastman – who said McCarthy was doing, however imperfectly, "a job that had to be done."

When the book was released, Buckley honored Senator McCarthy at a news conference where he presented the senator with a copy and declared that McCarthy was "the most smeared man in America."

When the book was released, Buckley honored Senator McCarthy at a news conference where he presented the senator with a copy and declared that McCarthy was "the most smeared man in America."

Later, in 2007, M. Stanton Evans (a friend and acolyte of Buckley's) released a voluminous book that brought forth much more information on McCarthy that had not been available to Buckley and Bozell in 1953. That book formed the basis for a ten-part series in this column – Parts 1-9 in late 2007 and Part 10 in May of 2008. The book by Evans was titled Blacklisted by History. Also shortly before our 2007 pieces, we did an examination of the late Edward R. Murrow's attack on McCarthy in two separate pieces shortly before the 1-9 installment in RenewAmerica

Alvin Felzenberg has given us a marvelous and comprehensive account of a man whose impact on American history in the late 20th and very early 21st centuries was tremendous, far greater than much of the public has realized – and all to the good of our nation. Some of us believe we may have barely missed a serious takeover in the "surprise" outcome of the 2016 election. We are now in danger of another civil war or total chaos in this country. Hopefully, we will have another William Buckley around before a real downfall is upon us.

© Wes Vernon

July 7, 2017

News and entertainment media, to say nothing of the history books, have inundated Americans with their own political versions of our nation's founding and of the political officials and other alert Americans who followed, including our 45 presidents (for whatever the proficiency of their efforts as "keepers of the flame" may have been). By no means, however, are those who made great strides in their contributions to the nation's direction confined to our elected or officially appointed public servants. In fact, some of those "outside the Washington bubble" had an impact that was much more than simply "noteworthy."

Seemingly no end to accomplishments

Seemingly no end to accomplishmentsSuch a power broker was the late William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925-2008). Unlike some others who quietly dispensed eagerly-received advice to "the power" in the White House Oval Office, Buckley's advice to Barry Goldwater and to Presidents Nixon, Reagan, Bush I, and Bush II was not only by frequent personal contact to the actual "seat of power"; some of it was very public, as in knowing that the political intellectual heavyweights Mr. Buckley was attempting to influence were subscribers to his conservative "must-read" magazine National Review. Actual influence? President George W. Bush summed it up: "Buckley brought conservative thought into the mainstream, and helped lay the intellectual foundation for America's victory in the Cold War."

The tribute was fitting, though it arguably left much to be added. That gap is filled admirably by Alvin S. Felzenberg in his new volume A Man and his Presidents: The Political Odyssey of William F. Buckley Jr. The author, aside from serving two administrations, is a professor of communications at the University of Pennsylvania and a historian in his own right, as shown, for example, in his 2008 Leaders We Deserved (and a Few We Didn't) – an outstanding and brutally honest rating of our first 42 presidents, excepting William Henry Harrison, whose presidency lasted all of one month.

Mr. Felzenberg also authored Governor Tom Kean: From the New Jersey Statehouse to the 9/11 Commission (2006). The author also served as the primary communications director for that panel. (You may recall having seen Al Felzenberg delivering a briefing to and taking questions from the media during the 9/11 hearings which Governor Kean chaired.)

A longtime attack aimed at America?

The "third party" presidential campaign of Henry A. Wallace in the 1948 Truman-Dewey contest was a candidacy that a very concerned Bill Buckley took very seriously at the time. Though Wallace ultimately received only 2.4 million popular votes and zero electoral votes, the former vice president (for Roosevelt) did attract a decent-sized intellectual contingent. His Progressive Party had been publicized for its backing and suspected funding by the Communist Party, which was able to gin up demonstrations in New York City. Buckley – a conservative young student, campus politician, and editor – pointed to history to support the point that "ideas advanced during elections could outlast losing campaigns, capture the imagination of intellectuals and under the right circumstances gain acceptance over time."

That might be cited as an example of Buckley's prescience, given the generations-long crawl from the meager vote for Henry Wallace, as the Democrat Party in the following generations seemed to veer

increasingly leftward in small increments until, in 2008, Americans could pull the lever for Barack Obama, who had been mentored by Frank Marshall Davis, an acknowledged Communist. Wallace later

sorrowfully recanted his communist leanings. Obama in his later time bore down on Marxist policies while never acknowledging the arguable origins of the ideas behind them. A more positive and much

shorter example of Buckley's point came when, in 1980, Ronald Reagan told Barry Goldwater that the latter had won his own presidential run in 1964, but "it just took us 16 years to count the votes."

That might be cited as an example of Buckley's prescience, given the generations-long crawl from the meager vote for Henry Wallace, as the Democrat Party in the following generations seemed to veer

increasingly leftward in small increments until, in 2008, Americans could pull the lever for Barack Obama, who had been mentored by Frank Marshall Davis, an acknowledged Communist. Wallace later

sorrowfully recanted his communist leanings. Obama in his later time bore down on Marxist policies while never acknowledging the arguable origins of the ideas behind them. A more positive and much

shorter example of Buckley's point came when, in 1980, Ronald Reagan told Barry Goldwater that the latter had won his own presidential run in 1964, but "it just took us 16 years to count the votes."True to its principles?

Beyond his very visible years at Yale, Buckley later emerged on the public scene as if he'd been shot out of a cannon. His first of what would be scores of books during the rest of his life was God and Man at Yale. Yale University was a secular institution whose students (in the majority) were nominally Protestant. The school was "conservative," though far more moderate than Buckley, who as a very devout Latin Mass-attending Catholic saw the teaching and the drift of Yale as having gradually taken on a rejection of Christianity and its vital teachings. He viewed Yale as ignoring Christianity, or in some instances, rejecting it. According to the author of A Man and his Presidents, Buckley wanted the university to teach that Christianity was superior to other faiths.

God and Man at Yale was the product of Buckley's own tussles – political and cultural – on the campus of the prestigious Ivy League institution (founded in 1701). This young man, during his student days there, notably was the editor and unabashedly opinionated (but also well-informed) editorial writer for the Yale Daily News. His time as "Chairman" at the paper reflected his stormy political activism as a student and portended what was to be his multiple-controversy-packed career in the decades to come.

What he really thought

Before he walked out the door at Yale, Buckley was selected to deliver the class day oration upon graduation. When those in charge of the event saw Buckley's prepared remarks, they advised him to tone them down before delivery.

Mr. Felzenberg quotes some prepared parts of the text, most of which Buckley insisted on delivering absent "references to specific individuals."

Mr. Felzenberg quotes some prepared parts of the text, most of which Buckley insisted on delivering absent "references to specific individuals."His comments included: "Here we find men who will tell us Jesus Christ was the greatest fraud that history has known." He said, in some classrooms conventional morality was presented as an anachronism "by human thought." He also urged Yale to proclaim that "collectivism [socialism] was inimical to individual dignity and to the nation's strength and prosperity." (One might add that collectivism, since Buckley's student days, has proven difficult to remove before or after it has done much of its damage (witness decades later the 2017 effort to "repeal and replace" Obamacare. – WV)

What says this senior guru of conservatism?

Both at Yale and later out in the real world, Buckley stirred controversy, and in the give and take of political battle found throughout the many years of his repertoire, Buckley was usually disciplined enough to know where to draw the line without losing the sharp edge he displayed as a masterful debater, at Yale and later on the worldwide political stage. His opponents respected him, and many of them befriended him without either they or he shedding their political convictions. His grip of an issue rarely if ever betrayed him when he was confronted with a debate opponent who was also well briefed of the arguments on both sides... Those were qualities that enabled Bill Buckley to come back week after week for years and face down the next comer on his popular Firing Line TV show. How else would his Firing Line last for 1429 TV episodes until it finally ended? He said he did not wish to "die on the set." (Obviously, he had the intellect and the concentration to multi-task. How else can one whose love of music enabled him the versatility to sit at the piano to play Bach with one hand and "Toot-Toot-Tootsie Good-bye" with the other?)

Then there were the columns in newspapers around the country – usually three per week – and scores of books, as well, while also meeting frequent speech-making demands Of course, the crown jewel of all of William F. Buckley's literary/media efforts is the magazine that started it all – his beloved National Review – "Buckley's magazine" as it was known. That fabled history about "standing athwart" the post-war political New Deal-accepting nation and shouting "Stop" was the turning point for America's post-war days. The magazine remains today on the web.

But there is more

"The Buckley era," best defined as 1945-1982 (starting at Yale) brought conservatism into the mainstream, as President Bush (see above) has said. At that time in history, much of Europe (the half not occupied by Soviet troops), and post-war media and other venues in America, were pushing or going along with a settling down with a collectivism-is-here-to stay attitude. William Buckley was not the only "voice in the wilderness" saying in so many words, hey what is this? Are we still America? Or are we willing to slowly (at first) drift away from the nation of our founders who fought so valiantly to make us an exceptional nation with a Constitution that is the backbone that has made us great?

The limits

The limitsOther conservatives arose, and Buckley welcomed or did not discourage them. But since much of America looked on him as an original steady hand and not a fly-by-night, he took on the job of noting publicly those who in his judgment were doing the cause more harm than good.

Dissenters voiced the Who-do-you-think-you-are retort. Some may have been put off by his transatlantic accent. (Note: Though the Buckleys were thoroughly American, they had some meaningful experiences elsewhere, as for example Bill's two years attending a prep school in England; that may be where he picked up the accent. It was no put-on. That's the way he talked. The woman who would later become his wife Pat, his "best friend," was the daughter of one of the most prominent citizens of Canada.)

Family fights?

Since William Buckley was generally recognized as a foremost post-war leader of conservatives, and was constantly besieged by media inquiring what he thought of this or that other conservative who had made some controversial remark, he felt (rightly or wrongly) that he had to try to draw what he considered the boundaries of what American conservatism was and what it was not.

Buckley publicly drew the lines on basically three or four sources of beyond-the-pale, as he viewed them. These included the "objectivist" group of the late libertarian author Ayn Rand. Their first meeting quickly deteriorated when Rand said to Buckley she could not understand how someone as intelligent as he could possibly believe in God. Her book Atlas Shrugged was roundly slammed in National Review by Whittaker Chambers, the ex-Communist who played a major role is exposing Alger Hiss as a traitor. Secondly, there was the John Birch Society, manly its leadership, which Buckley denounced. Bill Rusher, then a publisher for National Review, told me in the late nineties he had been in on the Buckley discussions of the Birch Society. At the time, he said he objected because well-meaning members of the Society were also fans of National Review. However, Rusher added in retrospect that he believes Buckley was right. And thirdly, the George Wallace segregationists. (Note: Governor Wallace once said to columnist Robert Novak, "You have never heard me call myself a "conservative.") Finally, Buckley ruled out anti-Semites as not deserving any seat at the conservative table.

The McCarthy book

Bill Buckley's second book, co-written with his brother-in-law Brent Bozell, Sr., was McCarthy and his Enemies, a defense of Senator Joseph McCarthy and his battle against Communism. Buckley and Bozell hailed the Wisconsin senator's fight to keep Communists out of government, while acknowledging the senator's lack of required political skills. Basically, they agreed with former leftist – and later National Review writer Max Eastman – who said McCarthy was doing, however imperfectly, "a job that had to be done."

When the book was released, Buckley honored Senator McCarthy at a news conference where he presented the senator with a copy and declared that McCarthy was "the most smeared man in America."

When the book was released, Buckley honored Senator McCarthy at a news conference where he presented the senator with a copy and declared that McCarthy was "the most smeared man in America."

Later, in 2007, M. Stanton Evans (a friend and acolyte of Buckley's) released a voluminous book that brought forth much more information on McCarthy that had not been available to Buckley and Bozell in 1953. That book formed the basis for a ten-part series in this column – Parts 1-9 in late 2007 and Part 10 in May of 2008. The book by Evans was titled Blacklisted by History. Also shortly before our 2007 pieces, we did an examination of the late Edward R. Murrow's attack on McCarthy in two separate pieces shortly before the 1-9 installment in RenewAmerica

Alvin Felzenberg has given us a marvelous and comprehensive account of a man whose impact on American history in the late 20th and very early 21st centuries was tremendous, far greater than much of the public has realized – and all to the good of our nation. Some of us believe we may have barely missed a serious takeover in the "surprise" outcome of the 2016 election. We are now in danger of another civil war or total chaos in this country. Hopefully, we will have another William Buckley around before a real downfall is upon us.

© Wes Vernon

The views expressed by RenewAmerica columnists are their own and do not necessarily reflect the position of RenewAmerica or its affiliates.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)